Rama Rajasekhara

Rajasekhara (fl. 9th century CE), identified with Rama Rajasekhara, was a Chera Perumal ruler of medieval Kerala, south India.[2][3][4] Rajasekhara is usually identified by historians with Cheraman Perumal Nayanar, the venerated Shaiva (Nayanar) poet-musician.[4][2][1] Two temple records, from Kurumattur, Areacode and Thiruvatruvay, Vazhappally, mention king Rajasekhara.[5]

| Rajasekhara | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sri Raja Rajadhiraja Parameswara Bhattaraka "Rajashekhara" Deva Peruman Adigal | |||||

_(cropped).jpg) Depiction of "Cherman Perumal" Nayanar in Brihadisvara Temple, Thanjavur | |||||

| Ruler of Kodungallur Chera (Perumal) Kingdom[1] | |||||

| Reign |

| ||||

| |||||

| Religion | Hinduism (Shaiva) | ||||

| Grantha | |||||

Rajasekhara is considered as one of the first independent kings of the Chera Perumal kingdom of Makotai.[6] Present-day central Kerala probably detached from Kongu Chera or Kerala kingdom (around 8th-9th century AD) to form the Chera Perumal kingdom.[7] Central Kerala was under some form of viceregal rule prior to this period.[8] It is also suggested that Cheraman Perumal Nayanar was on friendly terms with the Pallava dynasty.[8]

The direct authority of the Chera Perumal king was restricted to the country around capital Makotai (Mahodaya, present-day Kodungallur) in central Kerala.[9] His kingship was only ritual and remained nominal compared with the power that local chieftains (the udaiyavar) exercised politically and militarily. Nambudiri-Brahmins also possessed huge authority in religious and social subjects (the so-called ritual sovereignty combined with Brahmin oligarchy).[9][10]

Rama Rajasehara probably abdicated the throne toward the end of his reign and became a Shaiva nayanar known as Cheraman Perumal Nayanar.[5]

Sources

- Shivanandalahari, attributed to Hindu philosopher Shankara, indirectly mentions the Chera ruler as Rajasekhara.[11]

- Sanskrit poet Vasubhatta, described in Kerala traditions as a contemporary of the first Cheraman Perumal, refers to his first patron king as "Rama" and "Rama Rajasekhara" in the Yamaka kavyas Saurikathodaya and Tripuradahana respectively.[11] Vasubhatta names his second royal patron as "Kulasekhara" in his Yudhisthira Vijaya.[12]

- Rajasekhara is also tentatively identified with king "Co-qua-rangon" mentioned in the Thomas of Cana copper plates.[13]

Rama Deva

Laghu Bhaskariya Vyakhya, a mathematical commentary composed in the court of king Ravi Kulasekhara in 869/70 AD, mentions a Chera Perumal royal called Rama [Roma] Deva, who marched out to fight the enemies on getting information from the spies.[14] A possibility identifies Rama Deva with Rama Rajasekhara or with "[Vijaya]Raga Deva".[15]

Rama Deva is described as a member of the Solar Dynasty ("ravi-kula-pati") in Chapter IIII, Laghu Bhaskariya Vyakhya.[14]

Epigraphic records

| Date | Regnal Year | Language and Script | Location | Contents | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nature | Notes | ||||||

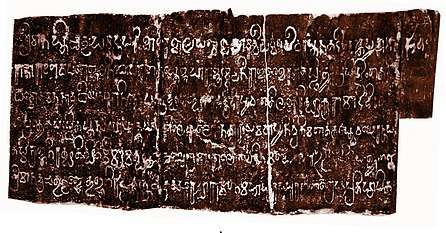

| 871 AD[5] | N/A | Grantha/Southern Pallava Grantha (Sanskrit)[16] | Kurumattur Vishnu temple, Areacode. - engraved on a loose, granite slab.[16][5] | Temple inscription[17] |

| ||

| c. 882/83 AD[5] | 13[20] | Vattezhuthu with Grantha/Southern Pallava Grantha characters (old Malayalam)[20] |

|

Temple committee resolution[20] |

| ||

References

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 64-65.

- Noburu Karashmia (ed.), A Concise History of South India: Issues and Interpretations. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014. 143.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 64-66, 88-95, 107.

- Veluthat, Kesavan. “The Temple and the State in Medieval South India.” Studies in People’s History, vol. 4, no. 1, June 2017, pp. 15–23.

- 'Changes in Land Relations during the Decline of the Cera State,' In Kesavan Veluthat and Donald R. Davis Jr. (eds), Irreverent History:- Essays for M.G.S. Narayanan, Primus Books, New Delhi, 2014. 74-75 and 78.

- Veluthat, Kesavan. 2004. 'Mahodayapuram-Kodungallur', in South-Indian Horizons, eds Jean-Luc Chevillard, Eva Wilden, and A. Murugaiyan, pp. 471–85. École Française D'Extrême-Orient.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 89-90 and 92-93.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 80-93.

- Noburu Karashmia (ed.), A Concise History of South India: Issues and Interpretations. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014. 143-44.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. 2002. ‘The State in the Era of the Ceraman Perumals of Kerala’, in State and Society in Premodern South India, eds R. Champakalakshmi, Kesavan Veluthat, and T. R. Venugopalan, pp.111–19. Thrissur, CosmoBooks.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 64 and 77.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 64-65.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumals of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy—Political and Social Conditions of Kerala Under the Cera Perumals of Makotai (c. AD 800–AD 1124) Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 302-303.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 64-66 and 78-79.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 79-80.

- Veluthat, Kesavan (1 June 2018). "History and historiography in constituting a region: The case of Kerala". Studies in People's History. 5 (1): 13–31.

- Indian Archaeology 2010-2011 – A Review (2016) (p. 118)

- Indian Archaeology 2010-2011 – A Review (2016) (p. 118)

- Naha, Abdul Latheef. Ancient inscription throws new light on Chera history. February 11, 2011 The Hindu

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 435.

- Rao, T. A. Gopinatha. Travancore Archaeological Series (Volume II, Part II). 8-14.

External links

- Mathew, Alex - Political identities in History (2006) Unpublished Doctoral Thesis (M. G. University)

.jpg)