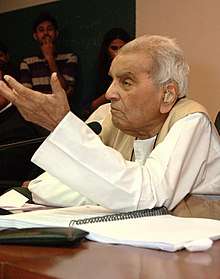

Rajinder Sachar

Rajindar Sachar (22 December 1923 – 20 April 2018) was an Indian lawyer and a former Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court.[1] He was a member of United Nations Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights and also served as a counsel for the People's Union for Civil Liberties.[2][3]

Rajindar Sachar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 22 December 1923 |

| Died | 20 April 2018 (aged 94) Delhi, India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Occupation | Lawyer, Judge |

| Known for | Civil rights activity |

Sachar chaired the Sachar Committee, constituted by the Government of India, which submitted a report on the social, economic and educational status of Muslims in India.[4] On 16 August 2011 Sachar was arrested in New Delhi during protests over the detention of Anna Hazare and his supporters.[5]

Early years

Rajindar Sachar was born on 22 December 1923.[1] His father was Bhim Sen Sachar.[6] His grandfather was a well-known criminal lawyer in Lahore.[7] He attended the D.A.V. High School in Lahore, then went on to Government College Lahore and Law College, Lahore.[1]

On 22 April 1952 Sachar enrolled as an advocate at Simla. On 8 December 1960 he became an advocate in the Supreme Court of India, engaging in a wide variety of cases concerning civil, criminal and revenue issues.[1] In 1963 a breakaway group of legislators left the Congress party and formed the independent "Prajatantra Party". Sachar helped this group prepare memoranda levelling charges of corruption and mal-administration against Pratap Singh Kairon, Chief Minister of the Indian state of Punjab. Justice Sudhi Ranjan Das was appointed to look into the charges, and in June 1964 found Kairon guilty on eight counts.[6]

Judge

On 12 February 1970 Sachar was appointed Additional Judge of the Delhi High Court for a two-year term, and on 12 February 1972 he was reappointed for another two years. On 5 July 1972 he was appointed a permanent Judge of the High Court. He was acting chief justice of the Sikkim High court from 16 May 1975 until 10 May 1976, when he was made a judge in the Rajasthan High Court.[1] The transfer from Sikkim to Rajasthan was made without Sachar's consent during the Emergency (June 1975 – March 1977) when elections and civil liberties were suspended.[8] Sachar was one of the judges that refused to follow the bidding of the Emergency establishment, and who were transferred as a form of punishment.[9] After the restoral of democracy, on 9 July 1977 he was transferred back to the Delhi High Court.[1]

In June 1977 Justice Sachar was appointed by the government to chair a committee that reviewed the Companies Act and the Monopolies and Restrictive Trade Practices Act, submitting an encyclopaedic report on the subject in August 1978.[10] Sachar's committee recommended a major overhaul of the corporate reporting system, and particularly of the approach to reporting on social impacts.[11] In May 1984 Sachar reviewed the Industrial Disputes Act, including the backlog of cases. His report was scathing. He said "A more horrendous and despairing situation can hardly be imagined... the load at present in the various Labour Courts and Industrial Tribunals is so disproportionate to what can conceivably be borne ... that the arrears can only go on increasing if the present state of affairs is not improved... It is harsh and unjust to both the employers and employees if the cases continue to remain undecided for years".[12]

In November 1984, Justice Sachar issued notice to the police on a writ petition filed by Public Union for Democratic Rights on the basis of evidence collected from 1984 Sikh riot victims, asking FIRs to be registered against leaders named in affidavits of victims. However, in the next hearing the case was removed from the Court of Mr. Sachar and brought before two other Judges, who impressed petitioners to withdraw their petition in the national interest, which they declined, then dismissed the petition.[13] Justice Sachar declared much later that his memory is still haunted by the reminiscence of not being able to get FIR registered in these cases.[14]

Sachar was Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court from 6 August 1985 until his retirement on 22 December 1985.[1]

Later career

Civil liberties

Sachar was one of the authors of a report issued on 22 April 1990 on behalf of the People's Union for Civil Liberties and others entitled "Report on Kashmir Situation".[15] In January 1992 Sachar was one of the signatories to an appeal to all Punjabis asking them to ensure that the forthcoming elections were free and were seen to be free. They asked the people to ensure there was no violence, coercion or unfair practices that would prevent the people from electing the government of their choice.[16] Sachar was appointed to a high-level Advisory Committee chaired by Chief Justice Aziz Mushabber Ahmadi to review the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993 and determine whether structural changes and amendments were needed. The committee prepared a draft amendment Bill incorporating its recommendations. These included changes to the membership of the National Human Rights Commission, changes to procedures to reduce delays in following up recommendations and a broadening of the commission's scope. The recommendations were submitted the Home Affairs ministry on 7 March 2000.[17]

In April 2003, as council for the People's Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL), Sachar argued before the Supreme Court of India that the Prevention of Terrorist Activities Act (POTA) should be quashed since it violated fundamental rights.[3] On 24 November 2002 the police arrested twenty six people in the Dharmapuri district of Tamil Nadu, and on 10 January 2003 they were placed under POTA by the government on the grounds that they were members of the Radical Youth League of the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist). On 26 August 2004, still being held without trial, the detainees began a hunger strike. Sachar led a team of human rights activists who visited them in jail on 15 September 2004 and persuaded them to end the hunger strike. POTA was repealed on 10 November 2004.[18] However, all the POTA provisions were incorporated in the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. In October 2009 Sachar called for abolition of these laws. He said "Terrorism is there, I admit, but in the name of terror probe, many innocent people are taken into custody without registering a charge and are being detained for long period".[19]

Housing rights

Sachar, who had formerly been a United Nations special rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing, headed a mission that investigated housing rights in Kenya for the Housing and Land Rights Committee of the Habitat International Coalition. In its report issued in March 2000 the mission found that the Kenyan government had failed to meet its international obligations regarding protection of its citizens' housing rights. The report described misallocation of public land, evictions and land-grabbing by corrupt politicians and bureaucrats.[20]

Rajindra Sachar participated with retired justices Hosbet Suresh and Siraj Mehfuz Daud in an investigation by the Indian People's Human Rights Tribunal into a massive slum clearance drive in Mumbai, which had the ostensible purpose of preserving the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. The demolitions on 22–23 January 2000 had been undertaken despite a notification from the state government to stay demolitions until September. The people had not been allowed to take the remains of their homes, which had been burnt. Sachar described the scene as "Barbaric, savage. It's as if a bomb has fallen here".[21] In August 2000 the judges, joined by former Supreme Court judge V. R. Krishna Iyer, held a two-day hearing into the clearances in which about 60,000 people had been evicted. The inquiry covered both legal aspects of the clearances and the human impact.[22]

Sachar headed a People's Court in 2002 to deliberate on people affected by evictions required to widen the Beliaghata Circular Canal in Kolkata, needed for health and safety purposes. Most of the people were poor handcart pullers, maidservants, hawkers and so on. The court called for consultation with the affected people as part of the project's decision-making process. They should be treated humanely, without force or coercion, and should not be evicted during periods of bad weather.[23]

Sachar committee

In March 2005 Justice Rajinder Sachar was appointed to a committee to study the condition of the Muslim community in India and to prepare a comprehensive report on their social, economic and educational status.[24] On 17 November 2006 he presented the report, entitled "Report on Social, Economic and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India", to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.[4] The report showed the growing social and economic insecurity that had been imposed on Muslims since independence sixty years earlier.[25] It found that the Muslim population, estimated at over 138 million in 2001, were under-represented in the civil service, police, military and in politics. Muslims were more likely to be poor, illiterate, unhealthy and to have trouble with the law than other Indians. Muslims were accused of being against the Indian state, of being terrorists, and politicians who tried to help them risked being accused of "appeasing" them.[26]

The Sachar Committee recommendations aimed to promote inclusion of the diverse communities in India and their equal treatment. It emphasised initiatives that were general rather than specific to any one community. It was a landmark in the debate on the Muslim question in India.[27] The speed of implementation would naturally depend on political factors including the extent of backlash from Hindutva groups.[27] The Sachar Committee Report recommended setting up an institutional structure for an Equal Opportunity Commission. An expert group was established that presented a report, including a draft bill to establish such a commission, in February 2008.[4] There was opposition. Thus, a speaker at a seminar in April 2008 sponsored by a group called "Bharatiya Vichar Manch" described the report as unconstitutional, saying "It should be rejected completely. It is on communal lines and will divide the country. It is a result of vote bank politics".[28]

Other activities

In 2003, as counsel for the Centre for Public Interest Litigation (CPIL), Sachar and Prashant Bhushan challenged the government's plans to privatise Bharat Petroleum and Hindustan Petroleum. CPIL said that the only way to disinvest in the companies would be to repeal or amend the Acts by which they were nationalised in the 1970s.[29] In December 2009 it was reported that Sachar was being proposed as Governor of West Bengal to replace Gopalkrishna Gandhi, whose term had expired.[30] In the event, Devanand Konwar was appointed acting governor.[31]

At the age of eighty-seven Sachar was detained by Delhi Police on 16 August 2011 during the India Against Corruption protest.[32] The arrest was for unlawful assembly and for making speeches in a location where a magistrate had declared the Section 144 rules were in force. [32] Sachar claimed that he knew the law and should not be arrested, but despite this he was taken into custody.[32]

Other statements

In 1989–1990 the Central Bureau of Investigation launched an inquiry into kickbacks in a government gun purchase deal. The inquiry was abandoned after the V. P. Singh government fell. Sachar called for the 500 pages of documents collected during the inquiry to be made public, saying: "There is no reason why the public should not be told of the full contents of the Bofors papers and only delay in disclosing the contents will unnecessarily expose the government to the charge of political manipulation".[33]

He said in 1992: "... the bureaucracy deviates from rules in the hope of basking in political favour. But this is short-term approach. Soon, the bureaucracy will find that after the massive ego and power lust of the politicians are satisfied, there comes a day when the bureaucrat is at the receiving end. And there is no one to support him because in league with politicians he has destroyed the strength of the public opinion. Bureaucrat is an unruly horse but has the potential to win the Derby, provided the Jockey is the expert, capable of giving proper motivation and desired direction. Politician with Bureaucratic mould of course, would do better,".[34]

In March 2003 Sachar was a signatory to a statement that condemned the US-led invasion of Iraq, calling it "unprovoked, unjustified, violates international law and constitut[ing] an act of aggression". Other signatories included Shanti Bhushan, Pavani Parameswara Rao, Rajeev Dhavan, Kapil Sibal and Prashant Bhushan.[35]

Commenting on the rise of crime against women, Sachar has stated that reservations for women in parliament could help eliminate gender bias in legal cases.[36] He has said "There are about 200 OBC[fn 1] candidates in the Lok Sabha. It is not their public service, but merely the caste configuration that has preferred them. Similar results will follow even after the reservation for women".[38]

Sachar has said: "I have deep faith in the judiciary ... like any other institution the judiciary may not have come up to the expectation; but that does not mean that the entire judiciary should be accused".[39] However, he has also spoken in favour of a national Judicial Commission, including members other than lawyers and judges, that would investigate issues concerning the administration of justice including the conduct of judges.[40] In 2003 he said: "There is an insistent public demand now that matters connected with appointments and misdemeanours of the higher judiciary need to be dealt with by an independent body using transparent means instead of the present unsatisfactory mechanism shrouded in secrecy".[41]

Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code outlaws disaffection against the state, and allows for penalties of life imprisonment. Jawaharlal Nehru told the Indian parliament in 1951 that "the sooner we get rid of it the better". In January 2012 Rajinder Sachar said "It seems tragic that we should be asking the government to redeem the pledge of Nehru. For having a democratic society, it is necessary that these laws go".[42]

Death

Sachar was suffering from ischemic heart disease and had an artificial cardiac pacemaker implanted. In April 2018, he was admitted to the Fortis Hospital in New Delhi, following complaint of recurrent vomiting. During the course of his treatment he contracted pneumonia and died on 20 April, Friday midnight. He was 94 years old. Sachar's body was cremated at Lodhi Road.[43][44][45][46]

Bibliography

- Rajindar Sachar, United Nations Centre for Human Rights (1996). The right to adequate housing. United Nations. p. 42. ISBN 9211541204.

- India. Prime Minister's High Level Committee, Rajindar Sachar (2007). High Level Committee Report on Social, Economic, and Educational Status of the Muslim Community of India, November 2006. Akalank Publications. p. 404.

References

- Notes

- OBC: Other Backward Class: Economically & socially backward castes and communities recognised by the National Commission for Backward Classes[37]

- Citations

- Former Judges.

- Chishti, Seema (21 April 2018). "Rajindar Sachar (1923-2018): Man of convictions, not shy of a fight for what is right". The Indian Express. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Time News 3 April 2003.

- Khaitan 2008.

- Jha 2011.

- Arora 1990, p. 102.

- Panikkar, Byres & Patnaik 2002, p. 570.

- Mirchandani 1977, p. 192.

- Ān̲ant 2010, p. 163.

- Sacher, Rajinder (31 August 1978). "Committee Report of the High-Powered Committee on Companies and MRTP Acts, 1978" (PDF). Ministry of Corporate Affairs. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Gupta 1995, p. 6.

- Ahuja 1997, pp. 753–754.

- "Memories of 1984". Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Living with Nightmare 1984:FIR's were not Registered:Pressure put on Delhi CJ Rajinder Sachar". Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Banerjee & Das 2005, p. 141.

- Aggarwal & Agrawal 1992, p. 183.

- Sen 2002, p. 328-329.

- Singh 2007, p. 239.

- Press Trust 2 October 2009.

- Leckie 2003, p. 226.

- "Crushed Homes, Lost Lives: The Story of the Demolitions in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park" (PDF). Savitribai Phule Pune University. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Express 5 August 2000.

- Banerjee & Das 2005, p. 136.

- Pratiyogita Darpan August 2006.

- Peer 2007, p. iv.

- Bigelow 2010, p. 14.

- Tellis & Wills 2007, p. 194.

- Express 27 April 2008.

- Ramakrishna 2004, p. 301.

- Padmanabhaiah, Sachar, Mamata.

- At farewell ...

- Zore 2011.

- Ghosh 1997, p. 406.

- Chitkara 1999, p. 76.

- Bhatnagar, Rakesh (30 March 2003). "Indian legal community criticises attack on Iraq". The Times of India. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Sachar, Rajindar (July 2003). "Women's reservation bill - A social necessity, national obligation". People's Union for Civil Liberties Bulletin. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- OBC.

- Mohammed 2011, p. 87-88.

- Mishra 2000, p. 588.

- Prasad 2006, p. 158.

- Johari 2007, p. 502.

- Vincent 2012.

- "Former Delhi HC Chief Justice Rajinder Sachar is no more". Deccan Herald. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Indo-Asian News Service (20 April 2018). "Justice Rajinder Sachar who led panel on condition of Muslims passes away". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Saigal, Sonam; Singh, Soibam Rocky (20 April 2018). "Former Delhi High Court Chief Justice Rajinder Sachar passes away". The Hindu. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- "Rajinder Sachar: Activist behind Sachar Committee report that highlighted condition of India's Muslims". The Indian Express. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- Sources

- Aggarwal, J. C.; Agrawal, S. P. (1992). Modern History of Punjab: A Look Back Into Ancient Peaceful Punjab Focusing Confrontation and Failures Leading to Present Punjab Problem, and a Peep Ahead : Relevant Select Documents. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 8170224314.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ahuja (1997). People, Law And Justice: Casebook On Public Interest Litigation, Volume 2. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 8125011897.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ān̲ant, Vi Kiruṣṇā (2010). India Since Independence: Making Sense of Indian Politics. Pearson Education India. ISBN 8131725677.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arora, Subhash Chander (1990). President's Rule in Indian States: A Study of Punjab. Mittal Publications. ISBN 8170992346.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "At farewell, Gopalkrishna Gandhi calls for change in mindsets". The Hindu. 13 December 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- Banerjee, Paula; Das, Samir Kumar (2005). Internal Displacement in South Asia: The Relevance of the Un's Guiding Principles. SAGE. ISBN 0761933298.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bigelow, Anna (2010). Sharing the Sacred: Practicing Pluralism in Muslim North India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195368231.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chitkara, M. G. (1999). World Government and Thakur Sen Negi. APH Publishing. ISBN 8176480320.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Express News Service (5 August 2000). "2-day public hearing under judicial tribunal". Indian Express. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- Express news service (27 April 2008). "'Sachar Committee report is unconstitutional'". The Indian Express. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- "Former Judges – Justice Rajinder Sachar". Delhi High Court. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- Ghosh, Srikanta (1997). Indian Democracy Derailed Politics and Politicians. APH Publishing. ISBN 8170248663.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gupta, Dr. Deepak (1995). Corporate Social Accountability: Disclosures and Practices. Mittal Publications. ISBN 817099621X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jha, Durgesh Nandan (16 August 2011). "Justice Sachar, children tie cops in knots". The Times of India. Retrieved 25 April 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johari, J. C. (2007). The Constitution of India a Politico-legal Study. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 8120726545.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Khaitan, Tarunabh (10 May 2008). "Dealing with discrimination". Frontline. The Hindu Group. Retrieved 24 April 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leckie, Scott (2003). National Perspectives on Housing Rights. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9041120130.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mirchandani, G. G. (1977). Subverting The Constitution. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 8170170575.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mishra, Shree Govind (2000). Democracy in India. Sanbun Publishers. ISBN 3473473057.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mohammed, Dr. Iqbal (2011). Reservation for Women in Governance in the 21st Century. Pinnacle Technology. ISBN 161820274X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Guidelines for Consideration of requests for Inclusion and complaints of under Inclusion in the central list of OBCs". National Commission for Backward Classes. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- "Padmanabhaiah, Sachar, Mamata favourites for governor". The Times of India. 23 December 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- Panikkar, K. N.; Byres, T. J.; Patnaik, Utsa (2002). The Making of History: Essays Presented to Irfan Habib. Anthem Press. ISBN 1843310384.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peer, Yasmeen (2007). Communal Violence in Gujarat: Rethinking the Role of Communalism and Institutionalized Injustices in India. ProQuest. ISBN 0549517537.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Prasad, Kamala (2006). Indian Administration: Politics, Policies, and Prospects. Pearson Education India. ISBN 8177589296.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Justice Sachar Committee's term Extended". Pratiyogita Darpan. 1 (2). August 2006.

- Press Trust of India (2 October 2009). "Innocent people victimised during terror probes: Activists". The Times of India. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- Ramakrishna, G. V. (2004). Two Score and Ten: My Experiences in Government. Academic Foundation. ISBN 8171883397.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sachar, Rajindar (1992). The Realization of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights: The Right to Adequate Housing : Working Paper. United Nations Sub-commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities. p. 25.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sen, Sankar (2002). Tryst with Law Enforcement and Human Rights: Four Decades in Indian Police. APH Publishing. ISBN 8176483400.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Singh, Ujjwal Kumar (2007). The State, Democracy And Anti-Terror Laws In India. SAGE. ISBN 0761935185.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tellis, Ashley J.; Wills, Michael (2007). Domestic Political Change and Grand Strategy. NBR. ISBN 0971393885.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Times News Network (3 April 2003). "PUCL urges Supreme Court to quash Pota". The Times of India. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- Vincent, Pheroze (31 January 2012). "Drive to scrap gag law". The Telegraph (India). Retrieved 25 April 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zore, Prasanna D (16 August 2011). "Justice Sachar detained at Anna fast venue". Rediff.com India News. Retrieved 24 April 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)