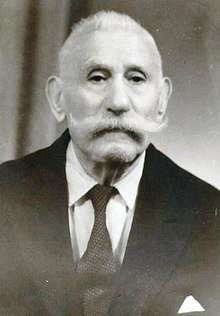

Rafael Moshe Kamhi

Rafael Moshe Kamhi (Bulgarian and Macedonian: Рафаел Моше Камхи, 1870–1970; military pseudonym Skander Beg)[2][3] was a Sephardic Jew from Monastir (now Bitola) in Ottoman Macedonia. Besides being Jewish, Kamhi felt also strong attachment to Macedonia as his native homeland.[4] Kamhi was elected as liaison officer of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO).[5] He directly participated in the Miss Stone Affair and in the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising of August 1903.

Rafael Moshe Kamhi | |

|---|---|

Rafael Moshe Kamhi (1963) | |

| Born | Рафаел Моше Камхи December 15, 1870[1] |

| Died | July 8, 1970 Tel Aviv, Israel |

| Nationality | Ottoman, Greek, Bulgarian, Israeli |

| Other names | Skander Beg |

Kamhi is among the few survivors of The Holocaust from Thessaloniki after being saved by Bulgarian authorities; 90% of the population was murdered.

Biography

Rafael Moshe Kamhi was born on 15 December 1870 in Bitola, Ottoman Empire (modern-day North Macedonia) in the family of Sephardi Jews. His father was Moshe Solomon Kamhi (1842–1891). At the end of 19th century around 4,000 Jews lived in Bitola.[6] Kamhi was educated at the Jewish Gymnasium and was multilingual: while he spoke Ladino, Turkish, Greek, French and Bulgarian. When he was 23 Kamhi decided to build for himself additional floor on his father's house. Later he hired there Fidan Gruev from Smilevo, an IMRO-activist who introduced him with his brother, Dame Gruev.[1] Afterwards he became de facto member of the IMRO in 1894 and in his house was made a shelter, where the archive and the case of the organization were kept. In the coming years Gotse Delchev, Gyorche Petrov, Milan Matov, Pere Toshev, Boris Sarafov and others also were hidden there. Later the shelter was discovered by the Ottoman authorities and Kamhi was arrested, but he was released after paying a bribe. In 1896, he was made de jure member and elected as Bitola-delegat on the Thessaloniki Congress of the organization. In Thessaloniki was taken a decision of changing the nationalistic character of the IMRO-statute, which determined its members can be only Bulgarians. In this way the IMRO was open to all inhabitants of European Turkey. In 1901–1902 he participated in the "Miss Stone Affair." After the decision to rise the Ilinden Uprising in 1903, Kamhi became responsible on the relations between the authorities in Bulgaria and the revolutionary organization. As a merchant he traveled often, and that made him convenient for that purpose. By these special trips he met with a number of Bulgarian politicians, including Ferdinand I and the Crown Prince, later Bulgarian Tsar - Boris III. Along with these frequent visits to Bulgaria, some of which involved his brother, they both were suspected and arrested by the Ottoman authorities. Subsequently, the brothers were interned in Debar.

Kamhi directly participated in the Ilinden uprising in Debar[7] while his brother, Menteš Kamhi (1877—1943), supplied rebels with weapons and other materials.[8] Later the brothers organized a campaign to raise funds to the victims of the uprising in the Jewish community in Macedonia. In 1905 Kamhi participated in the Rila Congress of IMRO.

After the subsequent split of the Organization, Kamhi maintained close links with left-wing activists of the Macedonian liberation movement as Gyorche Petrov and Dimo Hadzhidimov. He did not hide his dislike of the centralist's wing activists. The left-wing faction, opposed Bulgarian nationalism, but the centralist's faction drifted more and more towards it. After the Balkan wars Bitola remained in Serbia and he moved to Xanthi, then part of Bulgaria. At the end of World War I he joined the so-called Provisional representation of the former United Internal Revolutionary Organization. The Temporary representation advocated for autonomy of Macedonia as a part of a Balkan Federation. It threatened the autonomous Macedonia as a supranational state populated by different people as Bulgarians, Greeks, Serbs, Turks, Vlahs, Jews etc.[9][10] The Bulgarian government of Alexander Malinov offered at the end of the First World War in late 1918 the idea of a united autonomous Macedonian state under the jurisdiction of the Great Powers, but it was refused.[11] Due to the threat of a second national disaster for Bulgaria, before the signing of the Treaty of Neuilly, Kamhi conducted in 1919 a meeting with the then Prime Minister Teodor Teodorov, who struggled to keep order in the defeated country. He was offered to move to Thessaloniki, where the headquarters of the Triple Entente was located. He had to stand there with aim to present the interests of Bulgaria in Macedonia to the victors in the war. With the permission of the French General Charpy, he settled and stayed to live in the city. It is said he continued to work unofficially for Bulgarian interests in the period between the two World wars, when living in Greece.[12]

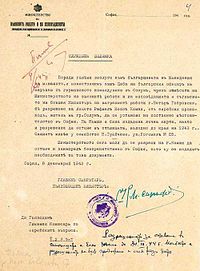

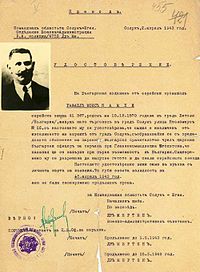

During World War II, after the occupation of Greece, Kamhi participated in the creation of Bulgarian Club in Thessaloniki. In 1943, Rafael Kamhi was arrested by the German occupying forces in the city and had to be sent to a concentration camp in Central Europe. With the support of Bulgarian organizations and institutions as the Macedonian Scientific Institute, the Ilinden (Organization), the Union of Macedonian brotherhoods, the premier Bogdan Filov, and Tsar Boris III himself, he was released. Meanwhile, nearly all 54,000 Salonica's Jews were shipped to the Nazi extermination camps. The Jewish communities of Bulgarian-controlled Yugoslavia and Greece territories, numbering 12,000 were also almost completely wiped out. Kamhi's brother, who lived in Bitola, together with his relatives there, and all his relatives in Thessaloniki, were deported in Treblinka. Nevertheless, 48,000 Bulgarian Jews native to the old borders of Bulgaria, were saved. Two of the few survivors were his niece Rosa and nephew Joseph Kamhi, the children of his brother. Rosa after the war married the Yugoslav General Beno Ruso and Joseph moved to Israel.

After his rescuing Kamhi moved to Sofia, where he remained until 1949, when he moved to Israel. After the war, at the request of the Macedonian Scientific Institute and the Jewish Institute in Sofia, he began working on his memoirs, still in Bulgaria. From Tel Aviv he continued his correspondence with both Institutes in Sofia. He died in ripe old age in 1970 in Tel Aviv.

Legacy

All the memories of Rafael Kamhi are now kept in the Bulgarian State Archive in the so-called Jewish collection of books and documents. The archives that he left contain documents in Bulgarian and Ladino. The collected memories of Rafael Kamhi were published under the title "I, the voyvoda Skender Bey" in 2000 in Sofia. In 2013, his memoirs were republished under the title "Rafael Kamhi: recollections of a Macedonian Jew revolutionary".

The first work of Macedonian historiography about Kamhi was written by Todor Simoski and published in 1953.[13]

In March 2011 the President of Macedonia addressed participants of the Central Commemorative gathering in remembrance of the Holocaust of the Macedonian Jews and emphasized that Kamhi "was one of the promoters of the idea of a free and independent Macedonia".[14] The Jewish Community in the Republic of Macedonia and Holocaust Memorial Fund of the Jews from Macedonia organized the event "Tribute to commander Rafael Kamhi and Heroes of Ilinden" during the national festival "10 days of the Krusevo Republic" in 2012.[15] A wax figure of Rafael Moshe Kamhi is among 109 wax figures of notable Macedonian revolutionaries and intellectuals exhibited at the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle in Skopje.[16]

Honours

Kamhi Point in Antarctica is named after Rafael Kamhi.[17]

References

- Stojanovski 2006, p. 42.

- Macedonian Review. Kulturen Zhivot. 1989. p. 11.

Rafael Moshe Kamhi, known by his military pseudonym of Skender Beg.

- Lebel, Jennie; Lebl, Ženi (30 April 2008). Tide and wreck: history of the Jews of Vardar Macedonia. Avotaynu. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-886223-37-0.

One of them, the best known of all, was Raphael Moshe Kamhi (1870-1970)

- Assa 1994, p. 78"This is one of the main reasons why Rafael Kamhi himself felt more like a Macedonian than a Jew. Like his fellow Macedonian Jews he loved Macedonia as his native land, the Macedonians as his brothers, and freedom as the primary aim of ..."

- Lebel, Jennie; Lebl, Ženi (30 April 2008). Tide and wreck: history of the Jews of Vardar Macedonia. Avotaynu. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-886223-37-0.

Raphael Kamhi was unanimously elected liaison officer of the VMRO

- Macedonian Review. Kulturen Zhivot. 1981. p. 51.

According to the 1890 census taken in the vilayets of Salonika, Monastir and Kosovo, 4,000 Jews lived in Bitola...

- Kolonomos, Žamila (1978). Poslovice, izreke i priče sefardskih Jevreja Makedonije. Savez Jevrejskih Ops̆tina Jugoslavije. p. 57.

...the Jewish communities of Macedonia supported Macedonian liberation movements within the limits of their possibilities and notion. In 1903 they gave active support to the »Ilinden« uprising. Rafael Kamhi participated directly in the uprising...

- Macedonian Review. Kulturen Zhivot. 1981. p. 51.

Rafael Kamhi participated directly in the uprising and was in permanent contact with the leadership of the movement. Mentes (Mentesh) Kamhi took weapons and other materials to the rebels.

- The IMARO activists saw the future autonomous Macedonia as a multinational polity, and did not pursue the self-determination of Macedonian Slavs as a separate ethnicity. Therefore, Macedonian was an umbrella term covering Bulgarians, Turks, Greeks, Vlachs, Albanians, Serbs, Jews, and so on. Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia, Historical Dictionaries of Europe, Dimitar Bechev, Scarecrow Press, 2009, ISBN 0810862956, Introduction.

- Statement of the Provisional Representation of the former United Internal Revolutionary Organization to the members of the Bulgarian Government, "Macedonia: documents and materials," Liubomir Panaĭotov, Voin Bozhinov, Bŭlgarska akademiia na naukite, 1978, str. 706.

- Gerginov, Kr., Bilyarski, Ts. Unpublished documents for Todor Alexandrov's activities 1910–1919, magazine VIS, book 2, 1987, p.214 – Гергинов, Кр. Билярски, Ц. Непубликувани документи за дейността на Тодор Александров 1910–1919, сп. ВИС, кн. 2 от 1987, с. 214.

- Вестник Сега, 22 Август 2000 г.: Спасеният евреин Рафаел Камхи изобличава.

- Karajanov 2003, p. 256: "Првиот податок во македонската историографија за Рафаел Камхи ќе го регистрира историчарот Тодбр Симовски во својата научна студија "За учеството на малцинствата во Илинденското востание", објавена во Зборникот на ИНИ... во 1953"

- Ivanov, Gjorge. "Address by the President of the Republic of Macedonia Dr. Gjorge Ivanov at the Central Commemorative gathering in remembrance of the Holocaust of the Macedonian Jews". Website of the president of the Republic of Macedonia. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

Therefore, we must never forget that, as Raphael Kamhi was one of the promoters of the idea of a free and independent Macedonia,....

- ""Tribute to Commander Rafael Kamhi and Heroes of Ilinden" ("Jewish evening")". Memorial Centre of the Holocaust of the Jews from Macedonia – Holocaust Fund of the Jews from Macedonia, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia. 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- "ХЕРОИТЕ НА ИЛИНДЕН - ЕВРЕИ". Web site Then-day Kruševo Republic. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

Рафаел Камхи – восочна фигура во Музејот на македонската борба за државност и самостојност

- Kamhi Point. SCAR Composite Gazetteer of Antarctica

Sources

- Assa, Aaron (1994) [First published in Bulgarian language in Jerusalem in 1972]. Macedonia and the Jewish people. Macedonian Review. ISBN 978-9989-645-02-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karajanov, Petar (2003). Rafael Moše Kamhi: ilindenski deec od evrejsko poteklo. Veda.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stojanovski, Aleksandar (2006). Македонија под турската власт: статии и други прилози. Ин-т за национална историја.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Рафаел Камхи: Спомени на един евреин македонски революционер, съставител: Цочо Билярски, издателство: Синева, ISBN 9786197086010, второ издание, 2013 год.

Further reading

- Камхи, Рафаел; Билярски, Цочо; Бурилкова, Ива (2000). Аз войводата Скендер Бей (in Bulgarian). Синева. ISBN 978-954-9983-03-6.