Russian Telegraph Agency

Russian Telegraph Agency (Russian: Российское телеграфное агентство, Rossiyskoye telegrafnoye agentstvo), abbr. ROSTA, was the state news agency in Soviet Russia (1918-35). After the creation of Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union in 1925, it remained the news agency of Soviet Russia. Its name was associated with Rosta windows (Russian: Окна Роста, Okna Rosta).

Rosta windows

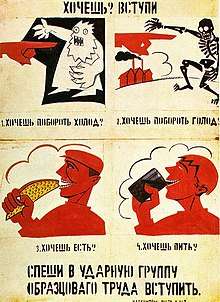

Rosta windows or satirical Rosta windows (Russian: Окна сатиры Роста, Okna satiry Rosta) were stencil-replicated propaganda posters created by artists and poets within the Rosta system, under the supervision of the Chief Committee of Political Education during 1919-21. Inheriting the Russian design traditions of lubok and rayok, the main topics were current political events. They were usually displayed in windows, hence the name.

The first Rosta window was created in Moscow by Mikhail Cheremnykh (1890-1962). He was soon joined by Vladimir Mayakovsky, a popular and prolific author, Dmitry Moor (1883-1946), Amshey Nurenberg (1887-1979), Alexander Rodchenko, Mikhail Volpin and others. Similar projects were performed in other Soviet cities. Cheremnykh and Mayakovsky, for example, produced a poster in 1921 satirising a French delegation led by Joseph Noulens.[1]

The design featured graphical simplicity suitable for viewing from distance and often used lubok-styled sequences of pictures according to some plot, similar to modern comics. The posters were not printed but rather painted with cut-out stencils made from cardboard. Once the required number of posters was painted, the stencils were sent to another city and put in circulation throughout the Soviet Union.

During the World War II, this approach was reproduced in Tass windows by Kukryniksy.

See also

- Media of Russia

External links

- Rosta Windows - Vladimir Mayakovsky (Russian)

- Parodies of Rosta Windows in the 1990s (Russian)

- ROSTA Posters exhibition(English)

Bibliography

- Ward, Alex (2008). Power to the People: Early Soviet Propaganda Posters in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. London, UK, Ashgate, ISBN 0-85331-981-2