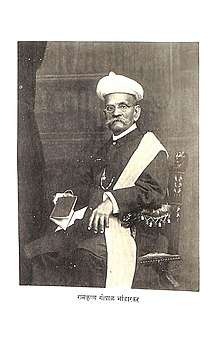

R. G. Bhandarkar

Sir Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarkar (Marathi: रामकृष्ण गोपाळ भांडारकर) KCIE (6 July 1837 – 24 August 1925) was an Indian scholar, orientalist, and social reformer.

Sir Ramakrishna Gopal Bhandarkar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 July 1837 |

| Died | 24 August 1925 (aged 88) |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Known for | Oriental studies |

| Children | Devadatta Ramakrishna Bhandarkar (son) |

| Signature | |

Early life

Bhandarkar was born in Malvan in Sindhudurg district of Maharashtra in a Goud Saraswat Brahmin family.[1] After early schooling in Ratnagiri, he studied at Elphinstone College in Bombay. Along with Mahadev Govind Ranade, Bhandarkar was among the first graduates in 1862 from Bombay University. He obtained his Master’s degree the following year, and was awarded a PhD from University of Göttingen in 1885.[2]

Career

Bhandarkar taught at Elphinstone College,(Mumbai) and Deccan College (Pune) during his distinguished teaching career. He was involved in research and writing throughout his life. He retired in 1894 as the Vice Chancellor of Bombay University. He participated in international conferences on Oriental Studies held in London (1874) and Vienna (1886), making invaluable contributions. Historian R. S. Sharma wrote of him: "He reconstructed the political history of the Deccan of the Satavahanas and the history of Vaishnavism and other sects. A great social reformer, through his researches he advocated widow marriages and castigated the evils of the caste system and child marriage."[3]

As an educationist, he was elected to the Council of India in 1903 as a non-official member. Gopal Krishna Gokhale was another member to the Council.[4] In 1911 Bhandarkar was awarded by the British colonial government of India with the title of Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire.[5]

Social reformer

In 1853, while a student, Bhandarkar became a member of the Paramhansa Sabha, an association for furthering liberal ideas which was then secret to avoid the wrath of the powerful and orthodox elements of contemporary society.[2] Visits from Keshub Chandra Sen during 1864 had inspired the members of the Sabha.

Prarthana Samaj

In 1866, some of the members held a meeting at the home of Atmaram Pandurang and publicly pledged to certain reforms, including:

- Denunciation of the caste system

- encouragement of widow remarriage

- encouragement of female education

- abolition of child marriage.

The members concluded that religious reforms were required as a basis for social reforms. They held their first prayer meeting on 31 March 1867, which eventually led to the formation of the Prarthana Samaj. Another visit by Keshub Chunder Sen and visits of Protap Chunder Mozoomdar and Navina Chandra Rai, founder of Punjab Brahmo Samaj, boosted their efforts.

Girls' Education

In 1885, Bhandarkar along with noted social reformers Vaman Abaji Modak, and Justice Ranade established the Maharashtra Girls Education Society (MGE) .[6] The society is the parent body of the first native run girls' high school in Pune popularly known as Huzurpaga.[7][8] The school curriculum included subjects such as English literature, Arithmetics and Science right from its founding.[9] The establishment of the school and its curriculum were vehemently opposed by Nationalist leader Lokmanya Tilak in his newspapers, the Mahratta and Kesari.[10][11]

Legacy

- The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute in Pune is named after him.[12]

References

- P. R. Dubhashi (2000). Building up a new university. p. 45.

The Saraswat Samaj has been traditionally cosmopolitan. It has produced great people like Ramakrishna Bhandarkar after whom the Bhandarkar Research Institute of Oriental Studies of Poona has been named

- "Ramkrishna Gopal Bhandarkar - orientalist par excellence". The Times of India. 12 July 2003.

- Sharma, R.S. (2009). Rethinking India's Past. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-569787-2.

- "India- Governor General Council". UK Parliament. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- Tikekar, Aroon and Tikekara, Aruna (2006), The Cloister's Pale: A Biography of the University of Mumbai, page 27, Popular Prakashan, Mumbai, India

- Ghurye, G. S. (1954). Social Change in Maharashtra, II. Sociological Bulletin, page 51.

- Bhattacharya, edited by Sabyasachi (2002). Education and the disprivileged : nineteenth and twentieth century India (1. publ. ed.). Hyderabad: Orient Longman. p. 239. ISBN 978-8125021926. Retrieved 12 September 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Huzurpaga". Huzurpaga.

- Bhattacharya, edited by Sabyasachi (2002). Education and the disprivileged : nineteenth and twentieth century India (1. publ. ed.). Hyderabad: Orient Longman. p. 240. ISBN 978-8125021926. Retrieved 12 September 2016.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Rao, P.V., 2008. Women's Education and the Nationalist Response in Western India: Part II–Higher Education. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 15(1), pp.141-148.

- Rao, P.V., 2007. Women's Education and the Nationalist Response in Western India: Part I-Basic Education. Indian Journal of Gender Studies, 14(2), p.307.

- http://www.bori.ac.in/ Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute