Arson in medieval Scandinavia

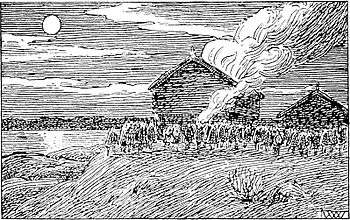

Arson in medieval Scandinavia (Old Norse hús-brenna or hús-bruni, "house-burning") was a technique sometimes employed in blood feuds and political conflicts in order to assassinate someone. In committing arson, a group of attackers would set fire to the home of an opponent, sometimes by quickly and surreptitiously piling wood, brush and other combustible materials against the exterior of a dwelling and set it on fire. Typically the attackers would surround the house to prevent the escape of its inhabitants, although women, the elderly, and small children were sometimes allowed to leave.[1][2]

In Iceland

Under Icelandic law as codified in the Gragas, quickfire could be punished by death only if the arsonists were killed in the act. However, if captured alive the arsonists had to be tried and sentenced to outlawry, even if they were thralls. Failure to observe these formalities could result in the killer of quickfire-arsonists being prosecuted himself.[3] At least some Icelanders considered quickfire dishonorable, hence when the enemies of Gunnar Hámundarson attacked his home they refused to burn him inside, despite the fact that it would have been faster and less costly in lives.[4] Members of Gunnar's clan showed no such scruples when, around 1010, they burned Bergthorshvoll, home of Gunnar's erstwhile ally Njáll Þorgeirsson, his wife Bergþóra, his sons Helgi and Skarphéðinn Njálsson, and his grandson Þórður Kárason. It is because of this occurrence of quickfire that the name of the saga in Icelandic is Brennu-Njáls saga, "The Saga of the Burning of Njáll". One son-in-law, Kári Sölmundarson, escaped and later killed many of the burners.[1] Here is the description of the arson of Njáll's house :

Now they took fire, and made a great pile before the doors. […] Then the women threw whey on the fire, and quenched it as fast as they lit it. Some, too, brought water, or slops. Then Kol Thorstein's son said to Flosi : "A plan comes into my mind; I have seen a loft over the hall among the crosstrees, and we will put the fire in there, and light it with the vetch-stack that stands just above the house."

Then they took the vetch-stack and set fire to it, and they who were inside were not aware of it till the whole hall was ablaze over their heads. Then Flosi and his men made a great pile before each of the doors, and then the women folk who were inside began to weep and to wail. […]

Now the whole house began to blaze. Then Njal went to the door and said : "Is Flosi so near that he can hear my voice?"

Flosi said that he could hear it.

"Wilt thou," said Njal, "take an atonement from my sons, or allow any men to go out?"

"I will not," answers Flosi, "take any atonement from thy sons, and now our dealings shall come to an end once for all, and I will not stir from this spot till they are all dead; but I will allow the women and children and house-carles to go out."

— The Story of Burnt Njal[5]

Another instance of quickfire is told in the Eyrbyggja Saga. According to it, in the late 10th century in Iceland, Ulfar, a freedman, was the victim of an attempted quickfire by thralls (slaves, or serfs) owned by his enemy Thorolf. Thorolf's own son, Arnkel Goði, captured the thralls in the act and had them executed the following day. Arnkel's rival Snorri Goði prosecuted Arnkel, at Thorolf's request, for the unlawful killing of the thralls.[6]

The Sturlunga saga reports that in 1253, during the Age of the Sturlungs, the Flugumýri Arson was an unsuccessful attempt on the life of Gissur Þorvaldsson by his Icelandic enemies. This account is quite similar to what is told in Brennu-Njáls saga : an assault against a house is faltering, so the attackers have the idea to use fire against the besieged defenders.[7] According to Lee M. Hollander, it is possible that this account inspired that of the burning of Njáll.[8] However, the episode of the burning of Njáll also appears in the Landnámabók and several other sources.[9]

In mainland Scandinavia

In both Norway and Sweden, arson had the specificity of being used by kings, either during succession wars (such as the civil war era in Norway) or during attempts at unification and expansion of territorial control by a king (for instance Harald Fairhair in Norway or Ingjald Illråde in Sweden). According to the medieval Swedish ballad Stolt Herr Alf, Odin himself advised a king to kill one of his vassals with quickfire.

Sweden

In Sweden, at least three kings are told as having used quickfire as a way to kill their opponents. The semi-legendary king Ingjald Illråde (who may have reigned in the 7th century) used quickfire at least twice: first he used it to kill several invited petty kings in order to directly rule their territories, and lastly he used it to kill Granmar, the last independent king of Södermanland.[10] The regnal list of the Westrogothic law gave the 11th-century Swedish king Anund Jakob (King of Sweden 1022 – c. 1050) the epithet "charcoal-burner" because of his methods. He was said to have been "generous in burning down men's homes".

According to the Orkneyinga saga and the Saga of Hervör and Heithrek, the exiled Swedish king Inge the Elder retook the Swedish throne by using quickfire against his pagan opponent Blot-Sweyn. This happened c. 1087 :

King Ingi set off with his retinue and some of his followers, thought it was but as small force. He then rode eastwards by Småland and into Östergötland and then into Sweden. He rode both day and night, and came upon Svein suddenly in the early morning. They caught him in his house and set it on fire and burned the band of men who were within. There was a baron called Thjof who was burnt inside. He had been previously in the retinue of Svein the Sacrificer. Svein himself left the house, but was slain immediately. Thus Ingi once more received the Kingdom of Sweden; and he reestablished Christianity and ruled the Kingdom till the end of his life, when he died in his bed. — The Saga of Hervör and Heithrek[11]

The Altuna Runestone[12] in Sweden also tells that a father and a son were burnt to death inside their home :

Vifast, Folkad, kuþar had this stone raised in memory of their father Holmfast [and of their brother] Arnfast. Father and son were both burnt in. And Balle and Frösten, Livsten's retainers [carved].[13]

Norway

In the Heimskringla, Snorri Sturluson records many accounts of quickfire used in the struggles between powerful men in Norway. According to him, Harald Fairhair, the Norwegian king traditionally credited with unifying Norway at the end of the 9th century, often used quickfire, as an alternative to, and in addition with, battles. One of his first deeds was the killing, either by fire or with weapons, of four petty kings in a single quickfire raid. According to Snorri, this allowed Harald to seize control over "Hedemark, Ringerike, Gudbrandsdal, Hadeland, Thoten, Raumarike, and the whole northern part of Vingulmark".[2] Later, Snorri recounts how arson was used to kill a rival king when a conventional armed expedition was not possible due to the season :

After this battle (A.D. 868) King Harald subdued South More; but Vemund, King Audbjorn's brother, still had Firdafylke. It was now late in harvest, and King Harald's men gave him the counsel not to proceed south-wards round Stad. Then King Harald set Earl Ragnvald over South and North More and also Raumsdal, and he had many people about him. King Harald returned to Throndhjem. The same winter (A.D. 869) Ragnvald went over Eid, and southwards to the Fjord district. There he heard news of King Vemund, and came by night to a place called Naustdal, where King Vemund was living in guest-quarters. Earl Ragnvald surrounded the house in which they were quartered, and burnt the king in it, together with ninety men. Then came Berdlukare to Earl Ragnvald with a complete armed long-ship, and they both returned to More. The earl took all the ships Vemund had, and all the goods he could get hold of. — Harald Harfarger's Saga, chapter 12.[2]

In contrast with Icelandic accounts of quickfire in the Brennu-Njáls saga and the Sturlunga saga, where it is used when a siege becomes difficult, accounts given by the Heimskringla of arsons in Norway rely heavily on surprise, and setting fire to the targeted house is the first thing done. Thus, surprise and good knowledge of the target's whereabouts are at a premium. This is shown by this account of an attempt by Gregorius Dagsson to kill Hákon herðibreiðr, who at that time (during the civil war era in Norway) vied for succession with Ingi Haraldsson :

Soon after Gregorius heard that Hakon and his men were at a farm called Saurby, which lies up beside the forest. Gregorius hastened there; came in the night; and supposing that King Hakon and Sigurd would be in the largest of the houses, set fire to the buildings there. But Hakon and his men were in the smaller house, and came forth, seeing the fire, to help their people. There Munan fell, a son of Ale Uskeynd, a brother of King Sigurd Hakon's father. Gregorius and his men killed him, because he was helping those whom they were burning within the house. Some escaped, but many were killed. […]

King Hakon and Sigurd escaped, but many of their people were killed. Thereafter Gregorius returned home to Konungahella. Soon after King Hakon and Sigurd went to Haldor Brynjolfson's farm of Vettaland, set fire to the house, and burnt it. Haldor went out, and was cut down instantly with his house-men; and in all there were about twenty men killed. Sigrid, Haldor's wife, was a sister of Gregorius, and they allowed her to escape into the forest in her night-shift only; but they took with them Amunde, who was a son of Gyrd Amundason and of Gyrid Dag's daughter, and a sister's son of Gregorius, and who was then a boy about five years old.

— Saga of Hakon Herdebreid (Hakon the Broad-Shouldered), chapter 13.[2]

Popular culture

- In Vikings, Ragnar Lothbrok murders his "former" enemy Jarl Borg's warriors by burning their couters.

- In Saxon Stories, and its TV adaptation, The Last Kingdom, the house of the adoptive father of the protagonist Uhtred of Bebbanburg, Earl Ragnar, burns in similar fashion.

References

- Njal's Saga § 129.

- Sturluson, Snorri (1844). Heimskringla. Laing, Samuel (trans.). London.

- Eyrbyggja Saga § 31. In this edition the translation given is simply "arson"; however, the earlier translation by William Morris and Eirikr Magnusson (Bernard Quaritch, London, 1892) uses the translation "quickfire".

- Njal's Saga § 77.

- Anonymous (1861). "128". The Story of Burnt Njal. George W. DaSent (trans.).

- Eyrbyggja Saga § 31.

- Ker, W.P. (2008) [1931]. Epic and Romance. BiblioBazaar (2008 reprinting).

- Anonymous (1998). Lee M. Hollander (ed.). Njals saga. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions.

- Lönnroth, Lars (1976). Njáls saga: a critical introduction. Berkeley: University of California Press.

there are also references to the fire.

- Sturluson, Snorri (1844). Heimskringla. Laing, Samuel (trans.). London., Ynglinga Saga Archived July 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, chapter 40

- The Saga of Hervör and Heithrek, in Stories and Ballads of the Far Past, translated from the Norse (Icelandic and Faroese), by N. Kershaw.Cambridge at the University Press, 1921. Archived 2006-12-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Jansson, S. B. F. (1987). Runes in Sweden. ISBN 91-7844-067-X p. 150

- Sawyer, Birgit (2003) [2000]. The Viking-Age Rune-Stones: Custom and Commemoration in Early Medieval Scandinavia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820643-7.

Bibliography

- Cook, Robert, trans. Njal's Saga. Penguin Classics, 2002.

- Lang, Samuel, trans. "Ynglinga Saga, or The Story of the Yngling Family from Odin to Halfdan the Black". Heimskringla. London, 1844; with corrections and edits by Douglas B. Killings; as published by northvegr.org, 2007.

- Palsson, Hermann and Paul Edwards, trans. Eyrbyggja Saga. Penguin Classics, 1989.