Pyrenean brook salamander

The Pyrenean brook salamander or Pyrenean newt (Catalan: tritó pirinenc; Basque: uhandre piriniarra; Spanish: tritón pirenaico), Calotriton asper, is a largely aquatic species of salamander in the family Salamandridae.[1][2] It is found in the Pyrenees of Andorra, France, and Spain. The IUCN lists it as "near threatened" due to habitat loss.[1]

| Pyrenean brook salamander | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Salamandridae |

| Genus: | Calotriton |

| Species: | C. asper |

| Binomial name | |

| Calotriton asper (Dugès, 1852) | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Description

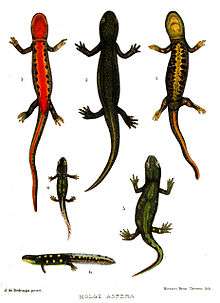

The Pyrenean brook salamander grows to about 16 cm (6.3 in) in length, half of which is the laterally flattened tail. The females are usually larger than the males. The body is sturdy with a flattened head and small eyes, and the limbs are short. There are no parotoid glands and the skin is covered with small, rough tubercles. The colour is very variable, the upper side usually being some shade of olive, grey, charcoal, or muddy brown, sometimes mottled with ochre, with an intermittent yellowish stripe down the spine. The underside has a row of dark splotches at either side and the centre is red, orange, or yellow. The male has a rounded cloacal swelling while the female has a conical one.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The Pyrenean brook salamander is endemic to the Pyrenees and surrounding mountains and is found at altitudes ranging from 700 to 2,500 metres (2,300 to 8,200 ft). It is a mostly aquatic species usually frequenting slow-moving streams and shallow mountain lakes. It favours water below 15 °C (59 °F) with scarce vegetation on rocky or pebbly bottoms.[3] Some Pyrenean brook salamanders live entirely inside caves where they breed over a long period of the year due to lack of day length stimulus.[4]

Biology

The Pyrenean brook salamander is infrequently seen, though it is active by day, as well as by night. It is mostly aquatic in summer. It feeds on insects and other slow-moving invertebrate prey, and is itself eaten by trout, so it is often scarce in locations in which they are abundant.[3] It is sensitive to pesticides in the water which are absorbed through the skin and accumulate in the tissues.[4]

The Pyrenean brook salamander sometimes aestivates in hot weather in the lower parts of its range. It hibernates in winter on land at higher altitudes, emerging in the spring. During courtship, the male displays his brightly coloured underparts before grasping the female around the loins with his tail and transferring one to four spermatophores directly into her cloaca in a process that lasts several hours. The female lays 20 to 40 eggs over the course of a few weeks, sticking them to rocks or inside crevices with her extensible cloaca. The eggs hatch after about six weeks; the larvae have external gills and are entirely carnivorous. They may overwinter one or more times before metamorphosis and become mature in two or more years, depending on altitude, with the females taking longer.[3] The juvenile newts are a dark colour with a thin, yellow line along the spine.[4]

References

- Bosch, J.; Tejedo, M.; Lecis, R.; Miaud, C.; Lizana, M.; Edgar, P.; Martínez-Solano, I.; Salvador, A.; García-París, M.; Recuero Gil, E.; Marquez, R. & Geniez, P. (2009). "Calotriton asper". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009: e.T59448A11943040. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009.RLTS.T59448A11943040.en.

- Frost, Darrel R. (2014). "Calotriton asper (Dugès, 1852)". Amphibian Species of the World: an Online Reference. Version 6.0. American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Arnold, Nicholas; Ovenden, Denys (2002). Reptiles and Amphibians of Britain and Europe. London: Harper Collins Publishers Ltd. pp. 37–38.

- "Calotriton asper". AmphibiaWeb. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

External links

Further reading

- Carranza, S. & Amat, F. (2005). "Taxonomy, biogeography and evolution of Euproctus (Amphibia: Salamandridae), with the resurrection of the genus Calotriton and the description of a new endemic species from the Iberian Peninsula" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 145 (4): 555–582. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00197.x.