Puerto Rican citizenship

Puerto Rican citizenship is the status of having citizenship of Puerto Rico as a concept distinct from having citizenship of the United States. Such a citizenship was first legislated in Article 7 of the Foraker Act of 1900[1][2] and later recognized in the Constitution of Puerto Rico.[3][4] Puerto Rican citizenship existed before the U.S. takeover of the islands of Puerto Rico and continued afterwards.[3][5] Its affirmative standing was also recognized before and after the creation of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico in 1952.[5][6] Puerto Rican citizenship was recognized by the United States Congress in the early twentieth century and continues unchanged after the creation of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico.[5][6][7] The United States government also continues to recognize a Puerto Rican nationality.[8] Puerto Rican citizenship is also recognized by the Spanish Government, which recognizes Puerto Ricans as a people with Puerto Rican, in addition to, U. S. citizenship.[9] It may also grant Spanish citizenship to Puerto Ricans on the basis of their Puerto Rican (and not American) citizenship.[9]

| Puerto Rican citizenship | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

|

|

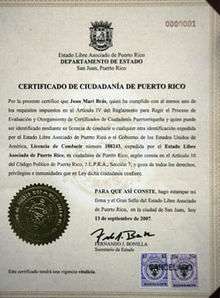

On 18 November 1997, the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico, through its ruling in Miriam J. Ramirez de Ferrer v. Juan Mari Brás, reaffirmed the standing existence of the Puerto Rican citizenship,[4] and on 25 October 2006, Puerto Rican Socialist Party president Juan Mari Brás became the first person to receive a Puerto Rican citizenship certificate from the Puerto Rico Department of State.[10] Since 2007, the Government of Puerto Rico has been issuing "Certificates of Puerto Rican Citizenship" to anyone born in Puerto Rico or to anyone born outside of Puerto Rico with at least one parent who was born in Puerto Rico.[11][12][13]

United States recognition of Puerto Rican citizenship

On 12 April 1900, the United States Congress enacted the Foraker Act of 1900, which replaced the governing military regime in Puerto Rico with a civil form of government. Section VII of this act created a Puerto Rican citizenship for the residents "born in Puerto Rico and, therefore, subject to its jurisdiction."[3] The Puerto Rican citizenship replaced the Spanish citizenship that Puerto Ricans held at the time[14] in 1898.[15] Such Puerto Rican citizenship was granted by Spain in 1897.[16] This citizenship was reaffirmed by the United States Supreme Court in 1904 by its ruling in Gonzales v. Williams which denied that Puerto Ricans were United States citizens and labeled them as noncitizen nationals.[17] In a 1914 letter of refusal to the offer of U.S. citizenship and addressed to both the President of the United States and the U.S. Congress, the Puerto Rico House of Delegates stated "We, Porto Ricans, Spanish-Americans, of Latin soul ... are satisfied with our own beloved Porto Rican citizenship, and proud to have been born and brethren in our own motherland."[18] The official 1916 Report by the American colonial governor of Puerto Rico to the U.S. Secretary of War (the former name for the Department of Defense[19]), addresses both citizenships, the Puerto Rican citizenship and United States citizenship,[20] in the context of the issuance of passports, further evidencing that the Puerto Rican citizenship did not disappear when the Americans took over the island in 1898.

Puerto Rican citizenship and Puerto Rican nationality

Since 2007, the Government of Puerto Rico has been issuing "Certificates of Puerto Rican Citizenship" to anyone born in Puerto Rico or to anyone born outside of Puerto Rico with at least one parent who was born in Puerto Rico. The Spanish Government recognizes Puerto Ricans as a people with Puerto Rican, "and not American", citizenship. It also provides Puerto Rican citizens privileges not provided to citizens of several other nations.[21] In 1942, a vote passed on HR 6165 to preserve Puerto Rican nationality.[22][23]

United States citizenship

On 2 March 1917, the Jones–Shafroth Act was signed, collectively making Puerto Ricans United States citizens without rescinding their Puerto Rican citizenship. In 1922, the U.S. Supreme court in the case of Balzac v. Porto Rico ruled that the full protection and rights of the U.S constitution do not apply to residents of Puerto Rico until they come to reside in the United States proper. Luis Muñoz Rivera, who participated in the creation of the Jones-Shafroth Act, gave a speech in the U.S. House floor that argued in favor of Puerto Rican citizenship. He declared that "if the earth were to swallow the island, Puerto Ricans would prefer American citizenship to any citizenship in the world. But as long as the island existed, the residents preferred Puerto Rican citizenship."[24] The Jones Act allowed locals to renounce the United States citizenship and remain exclusively Puerto Rican citizens, at the cost of being stripped of the right to vote.[25] At some point in time, 287 residents had formally done that.[25]

In 1952, upon the U.S. Congress approving the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, it also said that Puerto Rican citizenship continued in full force. This was further reiterated in 2006 while the U.S. Senate probed into the President's Task Force on Puerto Rico's status.[5] In 1953, U.S Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., in a memorandum sent to the United Nations, said that "the people of Puerto Rico continue to be citizens of the United States as well as of Puerto Rico."[6]

Puerto Rican citizenship reaffirmed

In 1994, Puerto Rican activist Juan Mari Brás flew to Venezuela and renounced his US citizenship before a consular agent in the US Embassy in Caracas.[26] Mari Brás, through his renunciation of U.S. citizenship, sought to redefine Section VII as a source of law that recognized a Puerto Rican nationality separate from that of the United States.[27] In December 1995, his renunciation was confirmed by the US State Department. Among the arguments that ensued over his action was whether he would now be able to vote in elections in Puerto Rico. On 18 November 1997, the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico, through its ruling in Miriam J. Ramirez de Ferrer v. Juan Mari Brás, reaffirmed Puerto Rican citizenship by ruling that U.S. citizenship was not a requirement to vote in Puerto Rico (on non-federal matters).[4] According to the court's majority opinion, Puerto Rican citizenship is recognized several times in the Puerto Rican constitution, including in section 5 of article III, section 3 of article IV, and section 9 of article V.[4] In a 2006 memorandum, the Secretary of Justice of Puerto Rico concluded, based on the Mari Brás case, that Puerto Rican citizenship is "separate and different" from the United States citizenship.[6]

The Puerto Rico Supreme Court decision affirmed that persons born in Puerto Rico and persons subject to their jurisdiction are citizens of Puerto Rico under the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico Constitution. The Court cited. as part of the applicable jurisdiction to decide this case, United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1875) pp. 549, the U.S. Supreme Court affirm: There is in our political system a government of each of the several States, and a Government of the United States. Each is distinct from the others, and has citizens of its own who owe it allegiance, and whose rights, within its jurisdiction, it must protect. The same person may be at the same time a citizen of the United States and a citizen of a State, but his rights of citizenship under one of those governments will be different from those he has under the other.[28]

Also the Puerto Rico Supreme Court cited U.S. Supreme Court case Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U.S. 1, 7 (1943) that affirmed: The protection extended to citizens of the United States by the privileges and immunities clause includes those rights and privileges which, under the laws and Constitution of the United States, are incident to citizenship of the United States, but does not include rights pertaining to state citizenship and derived solely from the relationship of the citizen and his state established by state law. The right to become a candidate for state office, like the right to vote for the election of state officers, is a right or privilege of state citizenship, not of national citizenship, which alone is protected by the privileges and immunities clause.[29]

The Puerto Rico Supreme Court affirmed that Puerto Rican citizenship identifies the persons that have it as integral members of the Puerto Rican community, saying this is the integral juridical tie between the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico and their citizens.[4] The court stated that "Puerto Rican political community is defined better by the citizenship of Puerto Rico than by US citizenship. That is a fact not subject to historical rectifications and a reality which no law can change."[26]

On 17 November 1997, Governor Pedro Rosselló signed Law 132 amending Puerto Rico's Political Code. The law states "Toda persona que posea la nacionalidad y sea ciudadano de los Estados Unidos y residente dentro de la jurisdicción del territorio de Puerto Rico será ciudadano de Puerto Rico" ("Every person who possesses the nationality and is a citizen of the United States and resides within the jurisdiction of the territory of Puerto Rico shall be a citizen of Puerto Rico").

Since the summer of 2007, the Puerto Rico State Department has developed a protocol to grant Puerto Rican citizenship certificates to Puerto Ricans.[30] Certificates of Puerto Rican citizenship are issued on request to any persons born on the island as well as to those born outside of the island that have at least one parent who was born on the island.[11][12]

Judicial review

In the case of Colon v. U.S. Department of State, 2 F.Supp.2d 43 (1998), plaintiff was a United States citizen born in Puerto Rico and resident of Puerto Rico, who executed an oath of renunciation before a consular officer at the U.S. Embassy in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. In rejecting Plaintiff's renunciation, the Department notes that Plaintiff demonstrated no intention of renouncing all ties to the United States. While Plaintiff claims to reject his United States citizenship, he nevertheless wants to remain a resident of Puerto Rico. Plaintiff's response to the Secretary's position is to claim a fundamental distinction between United States and Puerto Rican citizenship. The U.S. Department of State position asserts that renunciation of U.S. citizenship must entail renunciation of Puerto Rican citizenship as well. The court does decide to not enter to the merits of the citizenship issue; however the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia rejected Colon's petition for a writ of mandamus directing the Secretary of State to approve a Certificate of Loss of Nationality in the case because the plaintiff wanted to retain one of the primary benefits of U.S. citizenship while claiming he was not a U.S. citizen. The Court described the plaintiff as a person, "claiming to renounce all rights and privileges of United States citizenship, [while] Plaintiff wants to continue to exercise one of the fundamental rights of citizenship, namely to travel freely throughout the world and when he wants to, return and reside in the United States. The court based this decision on the Immigration and Nationality Act section 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(38), that provide the term "United States" definition and evince that Puerto Rico is a part of the United States for such purposes.[31][32][33]

Based on the federal court ruling on Colon v. U.S. Department of State, on 4 June 1998—and several months after the U.S. Government had accepted his renunciation—the U.S. State Department notified the president of the Puerto Rico Socialist Party, Juan Mari Brás, that they were rescinding their acceptance, and refused to accept Juan Mari Brás' renunciation, determining that Mari Brás could not renounce his American citizenship because he lived in Puerto Rico and not in another country foreign to the United States. This, said the federal agency, made Mari Brás a U.S. citizen.[34][35]

Application Form for

Certificate of Puerto Rican Citizenship

Reverse side of the Application Form for

Certificate of Puerto Rican Citizenship

International recognition

The Spanish government recognizes the Certificado de Ciudadania Puertorriqueña as a legitimate document.[36] Based on the Spanish Civil Code's Organic Law 4/2000 (enacted 11 January 2000 and amended by Royal Decree on 20 April 2011) which covers the awarding of the Spanish citizenship to foreigners, those that possess the document are considered Ibero-American nationals.[36] On 25 June 2007, the General Directory of Registry and Notary Affairs of the Ministry of Justice the passed RDGRN 25-06-2007, which recognized Puerto Rico as an Ibero-American country as far as the Spanish Civil Code is concerned.[36] To further confirm this stance, the Ministry of Justice has included Puerto Rico in their list of Ibero-American countries eligible to acquire the Spanish citizenship with priority, while also excluding the Caribbean countries of Jamaica, Haiti, Guyana, and Trinidad & Tobago.[36] The certificate of Puerto Rican citizenship is the foremost requisite to qualify under these circumstances.[36] The other requisite is at least two years of continuous residence in Spanish soil.[36] Puerto Ricans who only possess the United States citizenship are not considered residents of an Iberoamerican country and do not receive priority, requiring instead ten years of continuous residence.[36] In legal terms, Puerto Ricans who acquire Spanish citizenship with the use of the certificate would possess four citizenships recognized in Europe: those of Puerto Rico, the United States, Spain and the European Union (automatically granted along that of Spain).[36] On 23 September 2013, Representative Manuel Natal Albelo presented a bill that would render official the international recognition of the Puerto Rican citizenship through the Secretary of State, pursuing more rights within the international community.[37]

References

- Puerto Rican Immigrants: A Resource Guide for Teachers and Students. Warren Stevenson, Joshua Romano, Kaitlin Quinn-Stearns, and Thomas Kennedy. Fitchburg State University. Immigration and the American Identity, Dr. Laura Baker. TAH Program. Summer 2009. Page 2. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- The law that made Puerto Ricans U.S. citizens, yet not fully American: The Jones Act Was Part of a Legal Patchwork That Bolstered Commercial Ties to the Island but Treated Residents as Foreigners. Charles R. Venator-Santiago. University of Connecticut. Joe Mathews and Lisa Margonelli, editors. Zocalo Public Square. 6 March 2018. Accessed 233 June 2019.

- "Ley Foraker del 1900 de Puerto Rico". www.lexjuris.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 31 July 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- (Spanish) 97 DTS 135 – Ramírez de Ferrer v. Mari Brás

- Puerto Rico: Hearing before the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. US Senate. 109th Congress, 2nd Session on The Report by the President's Task Force on Puerto Rico's Status. 15 November 2006. page 114.

- "Opinion de Secretario de Justicia 2006-7" (PDF) (in Spanish). Gobierno de Puerto Rico. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- They say I am not an American…: The Noncitizen National and the Law of American Empire. Christina Duffy Burnett. Columbia University. 1 July 2008

- CIA World Factbook Found at: CIA World Factbook > Central America and Caribbean > Puerto Rico > People > Nationality. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- La eficacia y alcance del Certificado de Ciudadanía Puertorriqueña. Enrique Acosta Pumarejo. Microjuris. 30 August 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- "Race Space and the Puerto Rican Citizenship". academic.udayton.edu. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "(Spanish) Citizenship application. Puerto Rico Department of State". Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Departamento de Estado expedirá certificados de ciudadanía puertorriqueña

- Puertorriqueños pueden solicitar certificado de ciudadanía por internet. Primera Hora. San Juan, Purto Rico. 11 June 2007. Accessed 16 August 2020.

- Chronology of Puerto Rico in the Spanish–American War. US Library of Congress. Hispanic Division. In, "The World of 1898: The Spanish–American War." Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- Porto Rico Federal Reports, Vol II. United States District Court (Puerto Rico). Vol. II. Pages 470-473. United States District Court for the District of Porto Rico. Rochester, N.Y.: The Lawyers Cooperative Publishing Company. 1908. Retrieved 28 June 2012.

- "Citizenship in Puerto Rico: Question of the Status of the Island's 800,000 Inhabitants" The New York Times

- ""They say I am not an American…": The Noncitizen National and the Law of American Empire". 1 July 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Puerto Rico: Culture, Politics, and Identity. Nancy Morris. Greenwood Publishing Group. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers. 1995. Page 31. (From the Congressional Record 1914: 6718-20.) Retrieved 18 May 2012.

- National Security Act of 1947

- Department, United States War (16 August 1916). "Annual Report of the Secretary of War". U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved 16 August 2020 – via Google Books.

- La eficacia y alcance del Certificado de Ciudadanía Puertorriqueña. Enrique Acosta Pumarejo. Microjuris. 30 August 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- United States. Congress House (1941). Calendars of the United States House of Representatives and History of Legislation. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 162.

- "H.R. 6165" (PDF). Center for Puerto Rican Studies. US Congress. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- Maldonado, A. W. Luis Muñoz Marín: Puerto Rico's Democratic Revolution. Editorial UPR, 2006. P.35, ISBN 0-8477-0158-1

- Roberto Colón Ocasio (2009). Antonio Fernós Insern, Soberanista – Luis Muñoz Marín, Autonomista: Divergencias ideológicas y su efecto en el desarollo del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Fundación Antonio Fernós Insern, Inc. p. 37. ISBN 9781934461662.

- Efrén Rivera Ramos. American Colonialism in Puerto Rico: The Judicial and Social Legacy. Markus Wiener Publishers, 2007. p. 174. ISBN 1-55876-410-0.

- Ciudadanía Nacional de Puerto Rico. Juan Mari Brás Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine (Spanish).

- "United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1875)". U.S. Supreme Court. Justia.com U.S. Supreme Court Center. 1875. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- "Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U.S. 1 (1944)". U.S. Supreme Court. Justia.com U.S. Supreme Court Center. 17 January 1944. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- "Ciudadanía de Puerto Rico" (in Spanish). Departamento de Estado, Estado del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ""Renunciation of U.S. Citizenship". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Alberto O. Lozada Colon, Plaintiff, v. U.S. Department of State, et al., Defendants". The United States District Court, District of Columbia. Retrieved 15 January 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - See 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(36) and 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(38) Providing the term "State" and "United States" definitions on the U.S. Federal Code. 8 U.S.C. § 1101a

- Weekly News Update on the Americas. Archived 2012-09-07 at the Wayback Machine Nicaragua Solidarity Network of Greater New York. Issue #437, 14 June 1998. (News strip #12, "US State Department Denies Puerto Rican Citizenship.")

- "The San Juan Star--06/07/98". www.puertorico-herald.org. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Enrique Acosta Pumarejo (30 August 2013). "La eficacia y alcance del Certificado de Ciudadanía Puertorriqueña" (in Spanish). Microjuris.com. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- "Natal busca reconocer la ciudadanía puertorriqueña" (in Spanish). Metro Puerto Rico. 23 September 2013. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

External links

- Santos, José. A., Nuevo Certificado de Ciudadanía Puertorriqueña: Artículo que explica como el Certificado de Ciudadanía de Puerto Rico que expide el Departamento de Estado de PR, es un documento imprescindible e insustituible ante el Registro Civil Español para que, un puertorriqueño acredite el concepto de PR como país iberoamericano y adquirir su nacionalidad española .1 de noviembre de 2010. (Spanish)

- Application for Certificate of Citizenship of Puerto Rico (in Spanish)

- La eficacia y alcance del Certificado de Ciudadanía Puertorriqueña (Spanish)

- De extranjera ilegal a litigante en el Supremo: El caso de Isabel González influyó en las relaciones entre la Isla y EE.UU. Rut N. Tellado Domenech. El Nuevo Dia. 29 December 2013.(Spanish) Archived at the Wayback Machine on 1 January 2014.

- 7 FAM 1120 US State Dept Doc -On US Nationality vs. US Citizenship

- "Código Político de 1902", según enmendado (Spanish)

- Opinión del Secretario de Justicia de Puerto Rico en la Consulta Núm. 06-56-B hecha por el Secretario de Estado de Puerto Rico el 13 de septiembre de 2006 sobre si el Departamento de Estado en 2006 tenía la facultad para emitir una certificación reconociendo la condición jurídica del Lcdo. Juan Mari Brás como ciudadano de Puerto Rico. Específicamente, le solicitan que evaluaran si dicha acción es viable al amparo del caso Ramírez de Ferrer v. Mari Brás, 144 D.P.R. 141 (1997) ("Ramírez de Ferrer v. Mari Brás II". A esos fines, ellos examinado la jurisprudencia aplicable y las disposiciones de ley pertinentes, concluyen que el Departamento de Estado sí podía emitir la certificación solicitada, es decir el Certificado de Ciudadanía de Puerto Rico) (Spanish)

- Reglamento del Secretario de Estado 7347 para Regir el Proceso de Evaluación y Otorgamiento de Certificados de Ciudadanía Puertorriqueña (Spanish)

- LEY NUM. 132 DEL 17 DE NOVIEMBRE DE1997. Intento de Enmienda y deroga del Código Político de Puerto Rico 1902 que fracasa para eliminar el concepto de ciudadanía de Puerto Rico que recoge el Art 10 en su Título II (Spanish)

- RDGRN 25-06-2007. Resolución de 25 de junio de 2007, de la Dirección General de los Registros y del Notariado del Ministerio de Justicia Español, en el recurso interpuesto contra Resolución dictada por Encargado de Registro Civil Consular Español en Puerto Rico, en expediente sobre inscripción de nacimiento y opción a la nacionalidad española por un ciudadano de Puerto Rico de padre español. (Spanish)

- Tener la doble nacionalidad: ¿Qué implicaciones tiene la doble nacionalidad? Ministerio de Justicia Español. 18 August 2015. (Website of the Ministerio de Justicia Español where it explains how Puerto Ricans can have dual citizenship with their US citizenshipo.] (In Spanish)

- Acts of the Legislature of Puerto Rico. Acts and Resolutions of the First Session of the Second Legislative Assembly of Porto Rico (including the Organic Act of [US] Congress providing for a civil government). Government of Puerto Rico. (For information on Puerto Rican citizenship, see Section 7, page iv.) 1903. Accessed 28 July 2017.

- Extended Statehood in the Caribbean ~ Fifty Years of Commonwealth ~ The Contradictions Of Free Associated Statehood in Puerto Rico. Jorge Duany & Emilio Pantojas-Garcia. Rozenberg Quarterly: The Magazine. Dated c. July 2002.

- The Constitutionality of Decolonization by Associated Statehood: Puerto Rico's Legal Status Reconsidered. Gary Lawson Robert D. Sloane. Boston University School of Law. Working Paper No. 09-11. Revised 3 August 2009. Archived by the Wayback Machine on 18 October 2019.