Puddletown

Puddletown is a village and civil parish in Dorset, England. It is situated by the River Piddle, from which it derives its name, about 4.5 miles (7 km) northeast of the county town Dorchester. Its earlier name Piddletown fell out of favour, probably because of connotations of the word "piddle". The name Puddletown was officially sanctioned in the late 1950s. Puddletown's civil parish covers 2,908 hectares (7,185 acres) and extends to the River Frome to the south. In 2013 the estimated population of the civil parish was 1,450.

| Puddletown | |

|---|---|

.jpg) The Square, Puddletown | |

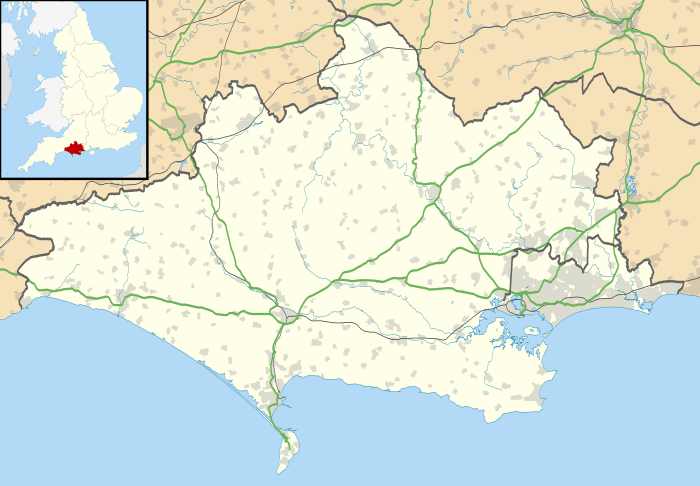

Puddletown Location within Dorset | |

| Population | 1,452 (2014 estimate) |

| OS grid reference | SY758943 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | DORCHESTER |

| Postcode district | DT2 |

| Dialling code | 01305 |

| Police | Dorset |

| Fire | Dorset and Wiltshire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Puddletown's parish church has significant architectural interest, particularly its furnishings and monuments. It has a 12th-century font and well-preserved woodwork, including 17th-century box pews. Thomas Hardy took an interest in the church, and the village provided the inspiration for the fictional settlement of Weatherbury in his novel Far from the Madding Crowd; Weatherbury Farm, the home of principal character Bathsheba Everdene, is based on a manor house within the parish.

Toponymy

The name Puddletown means 'farmstead on the River Piddle'. It derives from the Old English pidele, a river-name meaning fen or marsh, and tūn, meaning farmstead.[1] Several settlements along the river derive their names from it. In the upper reaches Piddletrenthide and Piddlehinton retain the piddle rivername, whereas downstream Puddletown, Tolpuddle, Affpuddle, Briantspuddle and Turners Puddle use puddle. In the Domesday Book of 1086 it was recorded as Pitretone, and in 1212 it was Pideleton.[1] John Speed used Puddletown for his county map of 1610.[2] In 1848 Samuel Lewis used Piddletown in A Topographical Dictionary of England.[3] In 1906 Sir Frederick Treves used Puddletown in Highways & Byways in Dorset—describing it as "the Town on the River Puddle" and a "curiously named place".[4] In 1946 Piddletown was the name on voters lists.[5] One explanation for the preference of Puddletown over Piddletown is that Major-General Charles William Thompson, who lived at Ilsington Lodge after returning from the Great War, pushed through the puddle variant because piddle had other connotations in army circles.[6] The broadcaster and writer Ralph Wightman (1901–71), a native of the Piddle Valley and one-time Puddletown resident,[6] believed it was due to Victorian "refinement", as he recalled that in his youth elderly aunts referred to Piddletrenthide as just "Trenthide".[5] Roland Gant in Dorset Villages stated more explicitly that the Victorians used puddle because piddle "became a euphemism for 'piss'".[7] The use of Puddletown rather than Piddletown was officially preserved in the late 1950s, when, according to Wightman, "a long County Council debate solemnly decided Piddletown should be Puddletown".[5][7]

The other rivers of the parish have names that derive from Celtic river-names: the Frome, which forms the parish's southern boundary, means "fair, fine or brisk",[8] and the Devil's Brook, which forms the north-eastern boundary, means "dark stream".[9]

History

Evidence of prehistoric human occupation in the parish exists in the form of 30 round barrows, about half of which are sited over chalk and half over Reading Beds. Many of the barrows have been damaged by more recent activities. The remains of strip lynchets of 'Celtic' fields have been found near a few of the barrows. One of the three 'Rainbarrows' on Duddle Heath has been excavated; bucket urns containing cremations from the site were taken to the Dorset County Museum.[10]

The Roman road between Durnovaria (now Dorchester) and Badbury Rings passed through the area of the civil parish; it cut a WSW-ENE route through Puddletown Heath, between the village and the River Frome.[10] In the 21st century a section of the road, which is 26 metres (85 ft) wide, was discovered in Puddletown Forest.[11]

Part of the arm of a 9th- or 10th-century stone cross was discovered when a house in the village—Styles House, near the River Piddle—was demolished. The cross might have been connected with a meeting place.[12] The fragment was incorporated into the parish church's new chancel when it was rebuilt in 1911.[13]

At the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, Puddletown was a large and important manor that contained several villages, with 1,600 sheep recorded.[14]

Except for Puddletown village, the several small settlements within Puddletown parish have all either diminished or disappeared. The other settlements were Cheselbourne Ford (beside the Devil's Brook in the northeast of the parish), Bardolfeston (about half a mile northeast of Puddletown village, just north of the River Piddle), Hyde (now Druce Farm), Waterston, South Louvard (now Higher Waterston), Little Piddle (now Little Puddle Farm in neighbouring Piddlehinton parish) and Ilsington (in the south of the parish, by the River Frome). Cheselbourne Ford and Bardolfeston are abandoned. Cheselbourne Ford had a population of six in 1086, four in 1327, and by the mid-seventeenth century was just one ruinous house. In 1970 its remains covered about 5.7 hectares (14 acres) and consisted of ten closes bounded by low banks, though the site is not shown on modern Ordnance Survey maps. Records indicate that Bardolfeston was declining by the 13th century and, though still occupied in the 16th, it was completely deserted by the 17th century. Its site covers about 6.1 hectares (15 acres) and is well-preserved, revealing a 12 metres (40 ft)-wide hollow way aligned southwest-northeast, with the sites of at least eleven houses alongside, though the southern end of the site was destroyed when watermeadows were later created along the river.[10][15] The site at Waterston consists of earthworks covering about 2 hectares (4.9 acres) on a terrace on the south side of the River Piddle. Its medieval population was relatively stable, and ten households were recorded in 1662. The site was probably abandoned gradually.[16]

In the early 17th century Puddletown was one of the first places in Dorset where the use of watermeadows developed; the practice occurred at least as early as 1620, and in 1629 the manorial court decided to allow some tenants to continue making the necessary watercourses that would enable "the watering and Improvinge of theire groundes".[17] Watermeadows are generally no longer used in southern England, though their physical remnants have persisted in many places;[18] in Puddletown civil parish, several areas of watermeadow were shown by the Ordnance Survey as late as 1978, though none was shown in 2010.[15][19]

Records from 1801 show that at that time agriculture was the main component of Puddletown's economy, though cottage industry and artisan crafts were also an important element: 596 people in the parish were primarily employed in agriculture, with 221 employed in handicrafts, manufacture and trade. Cottage industry, often undertaken by women and children, was used to supplement agricultural income, though there were fewer opportunities for this after the French Revolution.[20]

In 1830 Puddletown was one of the places in Dorset where agricultural labourers took part in the Captain Swing riots of southern England, protesting against very low wages and long working hours. Threshing machines were damaged and ricks burned. Wages were raised from about six or seven shillings per week to ten as a result.[21]

To the east of the church is Ilsington House, also known as the Old Manor, which was built in the late 17th to early 18th century.[22] It was originally owned by the 3rd Earl of Huntingdon and in 1724 by Robert Walpole. Between 1780 and 1830 it was leased to General Thomas Garth, principal equerry to King George III. The General adopted King George III's illegitimate grandson by Princess Sophia, and brought him up at the manor.[6] In 1861 the house was acquired by John Brymer and remained in the possession of the Brymer family for the next century.[6][23] The family built new cottages and a reading room in the village, and a new manor next to the church, which they restored.[24]

Governance

In the UK national parliament, Puddletown is within the West Dorset parliamentary constituency, which is currently represented by Oliver Letwin of the Conservative Party. In local government, Puddletown is governed by Dorset Council at the highest tier, and Puddletown Area Parish Council at the lowest tier.[25]

In national parliament and district council elections, Dorset is divided into several electoral wards, with Puddletown lying within Puddletown ward.[26][27][28] In county council elections, Dorset is divided into 42 electoral divisions, with Puddletown being within Linden Lea Electoral Division.[29]

Geography

Puddletown civil parish extends between the flood plain and watermeadows of the River Frome in the south to the chalk watershed of Puddletown Down in the north.[15][30] It covers 2,908 hectares (7,185 acres) and is bisected by the River Piddle, which crosses it from west to east.[10] Measured directly, Puddletown village is about 4.5 miles (7.2 km) northeast of Dorchester, 16 miles (26 km) west of Poole and 11 miles (18 km) southwest of Blandford Forum.[31]

The bedrock geology of the parish comprises rocks formed in the Santonian and Campanian ages of the Cretaceous period and the Eocene age of the Palaeogene period. In places these are overlain by younger Quaternary drift material: river terrace and head deposits, clay-with-flints, and alluvium—the last found only in the valley floors of the larger watercourses.[30] On Puddletown Heath (now mostly covered by Puddletown Forest) are more than 370 solution hollows or sinkholes; these constitute the largest concentration of hollows on the heathlands in the area.[32]

The River Frome, which forms the southern boundary of the parish, is designated by Natural England as a Site of Special Scientific Interest.[33] Southwest of the village and almost wholly within the parish is Puddletown Forest, which covers 301 hectares (740 acres) and is managed by the Forestry Commission. The forest is on the edge of the Dorset Heaths Natural Area and some of the forest is being restored to heathland; the heath flora consists of Calluna, Ulex gallii, Ulex minor and bilberry; fauna includes the rare smooth snake and sand lizard. Close to Puddletown Forest are Yellowham Wood and Ilsington Wood, which are ancient woodland sites, though Ilsington Wood has significant conifer plantings.[34]

Demography

In 2014 the estimated population of Puddletown civil parish was 1,452.[35] Figures from the 2011 census have been published for Puddletown parish combined with the small parish of Athelhampton to the east; in this area there were 663 dwellings,[36] 614 households and a population of 1,405.[37]

Notable buildings

Excluding ancient earthworks, there are fifty-six structures within the parish that are listed by Historic England for their historic or architectural interest, including two (the parish church and Waterston Manor) that are listed as Grade I, and three (Ilsington House, The Old Vicarage, and 8 The Square) that are Grade II*.[38][39]

Puddletown's parish church, dedicated to St Mary, has been described as being "of considerable architectural interest",[10] "of exceptional interest for its furnishings and monuments"[40] and "one of the most exciting parish churches in the county".[41] It has 12th-century origins—parts of the tower date from 1180–1200[41]—but was rebuilt and enlarged between the 13th and 16th centuries.[10][40] The 12th-century font is particularly notable, being of a tapering beaker shape, with diapering depicting crossing stems and Acanthus leaves; its cover is an octagonal pyramid dating from about 1635, when the church interior was refitted.[6][10] There is a panelled roof in the nave, and 17th-century box pews, pulpit and gallery. There are also a number of 15th- and 16th-century monumental brasses and some stained glass by Ninian Comper.[42] The South or Martyn family chapel has three 16th-century tombs with alabaster effigies. In 1910 the church was partially restored by Charles Ponting.[10][40] Thomas Hardy led an unsuccessful campaign to prevent enlargement of the original chancel.[41]

Waterston Manor, about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) WNW of Puddletown village, is of early 17th-century origin, though it was largely rebuilt after a fire in 1863, and altered again in about 1911.[43]

Ilsington House dates from the late 17th to early 18th century, with alterations made in the late 18th to early 19th century and enlargement later in the 19th. It has plaster-covered brick walls, quoins of ashlar, and a hipped slate roof.[22] In 2000 it was presented with a "Dorset Architectural Heritage Award".[23]

The Old Vicarage, previously the east wing of the vicarage, was originally a timber-framed building built about 1600. It was clad in brick in the 18th century (after the vicarage had been extended west in 1722) and a third storey added early in the 19th century. The 1722 west-wing extension became 8 The Square and is listed separately.[10][44][45]

Community facilities

Puddletown has a village hall, which has a kitchen and bar, full disabled facilities and access, and a capacity for between 100 and 160.[46] Since 2013 it has also housed Puddletown Community Library, which is operated solely by volunteers.[47] On Athelhampton Road there is a doctor's surgery, which also treats patients who live in surrounding villages.[48] Puddletown has a recreation ground on Three Lanes Way; it has one cricket pitch and two grass football pitches (one junior, one full-size).[49]

Literary connections

Puddletown is the basis for the village of "Weatherbury" in Thomas Hardy's novel Far from the Madding Crowd.[6] Weatherbury Farm, the house of Bathsheba Everdene, is based on Waterston Manor, between Puddletown and Piddlehinton.[50] Hardy's cousin, Tryphena Sparks, who was the inspiration for Hardy's poem Thoughts of Phena at News of Her Death, lived in Puddletown.[51]

Notable people

Cardinal Pole, the last Roman Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury, was vicar of the parish from 1532 to 1536.[41] The author and broadcaster Ralph Wightman (1901–1971) lived in Puddletown in the later years of his life; he lived in the 16th-century Tudor Cottage in The Square.[6][10] The writer Constantine Fitzgibbon (1919–1983) owned Waterston Manor for part of the 20th century.[50]

See also

- Puddletown Hundred

References

Notes

- Mills, David (2011). A Dictionary of British Place Names. Oxford University Press. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-19-960908-6.

- "John Speed's Map of Dorset 1610". Charmouth Local History Society. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- Lewis, Samuel (1848). A Topographical Dictionary of England. British History Online. pp. 567–571. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- Treves, Sir Frederick (1906). Highways & Byways in Dorset. Macmillan and Co. Ltd. pp. 365–6.

- Wightman 1983, p. 70.

- Hannay, Clive; Legg, Rodney (September 2006). "Puddletown". Dorset Life Magazine. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- Gant 1980, p. 188.

- Mills, David (2011). A Dictionary of British Place Names. Oxford University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-19-960908-6.

- Mills, David (2011). A Dictionary of British Place Names. Oxford University Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-19-960908-6.

- "'Puddletown', in An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 3, Central (London, 1970), pp. 222–231". British History Online. University of London. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- MacDonagh, Diarmuid (29 January 2011). "Roman road found in Puddletown Forest". dorsetecho.co.uk. Newsquest Media (Southern) Ltd. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Baker, John; Brookes, Stuart (2015). "Identifying outdoor assembly sites in early medieval England" (PDF). Journal of Field Archaeology. University of Nottingham. 40 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1179/0093469014z.000000000103. ISSN 0093-4690.

- Cramp, Rosemary (2006). Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture: South-West England. British Academy. p. 108. ISBN 9780197263341.

- J H Bettey (1974). Dorset. City & County Histories. David & Charles. pp. 34–39. ISBN 0-7153-6371-9.

- Ordnance Survey (1978) 1:25,000 Second Series, Sheet SY 69/79 (Dorchester)

- "Medieval settlement immediately west of Waterston House". Historic England. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- J H Bettey. "The Development of Water Meadows in Dorset during the Seventeenth Century" (PDF). bahs.org.uk (British Agricultural History Society) (scan). pp. 37–39. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- Bettey, Joseph (1999). "The Development of Water Meadows in the Southern Counties". In Hadrian Cook; Tom Williamson (eds.). Water Management in the English Landscape (PDF). Edinburgh University Press. pp. 179–195. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Ordnance Survey (2010) 1:25,000 Explorer Series, Sheet 117 (Cerne Abbas & Bere Regis), ISBN 978-0-319-24122-6

- Ottaway, Susannah R. (2004). The Decline of Life: Old Age in Eighteenth-Century England. Cambridge University Press. pp. 191–192. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- J H Bettey (1974). Dorset. City & County Histories. David & Charles. pp. 136–137. ISBN 0-7153-6371-9.

- "Ilsington House, Puddletown". British Listed Buildings. britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Maslen, Adrianne (7 July 2010). "Dorset's Ilsington Estate on sale for £18million". dorsetecho.co.uk. Newsquest Media (Southern) Ltd. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- Wightman 1983, p. 75.

- "Welcome to the Puddletown Area Parish Council Website". Puddletown Area Parish Council. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- "The West Dorset (Electoral Changes) Order 2015". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- "Dorset West: Seat, Ward and Prediction Details". electoralcalculus.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- "Interactive map of District councillors". dorsetforyou.com. Dorset County Council. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- "Electoral division profiles 2013". dorsetforyou.com. Dorset County Council. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- British Geological Survey (2000) 1:50,000 Series, Sheet 328 (Dorchester), ISBN 0-7518-3310-X

- Bartholomew (1980) 1:100,000 National Map Series, Sheet 4 (Dorset), ISBN 0-7028-0327-8

- Goudie, A. S.; Gardner, R. (2013) [1992]. Discovering Landscape in England & Wales. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 136–7. ISBN 978-0-412-47850-5.

- "COUNTY: DORSET. SITE NAME: RIVER FROME" (PDF). naturalengland.org.uk. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- "Plan Name: Puddletown" (PDF). Forestry Commission. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- "Area Profile for Puddletown & Athelhampton". geowessex.com. Dorset County Council. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- "Area: Puddletown (Parish). Dwellings, Household Spaces and Accommodation Type, 2011 (KS401EW)". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "Area: Puddletown (Parish), Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Listed Buildings in Puddletown, West Dorset, Dorset". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- "Search Results for 'Puddletown'". Historic England. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- "Church of Saint Mary, Puddletown". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "Puddletown St Mary's". The Dorset Historic Churches Trust. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- Betjeman, John, ed. (1968) Collins Pocket Guide to English Parish Churches; the South. London: Collins; p. 176

- "Waterston Manor, Puddletown". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- "The Old Vicarage Including Garden Walls Adjoining Islington House, Puddletown". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "8 the Square, Puddletown". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "Puddletown Village Hall". Dorset Halls Network. Dorset Village Halls Association. 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- "Welcome to Puddletown Community Library". communitylibrarypuddletown.org. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Puddletown Surgery". puddletownsurgery.co.uk. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Puddletown Recreation Ground". sports-facilities.co.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- Gant 1980, p. 190.

- Millgate, Michael Thomas Hardy: a biography revisited (2004) Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-927566-1

General references

- Gant, Roland (1980). Dorset Villages. Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 0-7091-8135-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wightman, Ralph (1983). Portrait of Dorset (4 ed.). Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 0-7090-0844-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Puddletown. |