Tasmanian giant crab

The Tasmanian giant crab, Pseudocarcinus gigas (sometimes known as the giant deepwater crab, giant southern crab or queen crab) is a very large species of crab that resides on rocky and muddy bottoms in the oceans off Southern Australia.[2][3] It is the only species in the genus Pseudocarcinus.[4]

| Tasmanian giant crab | |

|---|---|

| |

| male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Infraorder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Pseudocarcinus H. Milne-Edwards, 1834 |

| Species: | P. gigas |

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudocarcinus gigas (Lamarck, 1818) | |

| Synonyms [1] | |

|

Cancer gigas Lamarck, 1818 | |

Habitat

The Tasmanian giant crab lives on rocky and muddy bottoms in the oceans off Southern Australia on the edge of the continental shelf at depths of 20–820 metres (66–2,690 ft).[2][3] It is most abundant at 110–180 metres (360–590 ft) in the summer and 190–400 metres (620–1,310 ft) in the winter.[3] The seasonal movements generally follow temperature as it prefers 12–14 °C (54–57 °F).[3] The full temperature range where the species can be seen appears to be 10–18 °C (50–64 °F).[5]

Description

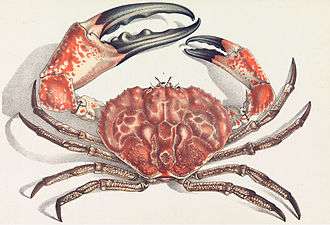

The Tasmanian giant crab is one of the largest crabs in the world, reaching a mass of 17.6 kg (39 lb) and a carapace width of up to 46 cm (18 in).[6] Among crabs only the Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi) can weigh more.[5] Male Tasmanian giant crabs reach more than twice the size of females,[7] which do not exceed 7 kg (15 lb).[6] Males have one normal-sized and one oversized claw (which can be longer than the carapace width[5]), while both claws are normal-sized in the females.[6] This crab is mainly whitish-yellow below and red above; the tips of the claws are black.[8] Small individuals are yellowish-and-red spotted above.[5]

Behaviour

The Tasmanian giant crab feeds on carrion and slow-moving species, including gastropods, crustaceans (anomura and brachyura) and starfish.[3][7] Cannibalism also occurs.[3] They breed in June and July, and the female carries the 0.5–2 million eggs for about four months.[7] After hatching, the planktonic larvae float with the current for about two months before settling on the bottom.[5] The species is long-lived and slow-growing; juveniles moult their carapace every three-four years and adult females about once every nine years.[5][6] This greatly limits the breeding frequency, as mating is only possible in the period immediately after the old carapace has been shed, and the new is still soft.[6]

Fishery

The Tasmanian giant crab has been commercially fished in Tasmanian waters since 1992 and a minimum size was established in Australia in 1993.[7] Fishing is typically by pots in water deeper than 140 m (460 ft).[6] Following concerns surrounding the sustainability of catch numbers, the total allowable catch was adjusted in 2004 to 62.1 tonnes (137,000 lb).[9] Twenty-five operators competed for the catch in 2005, delivering a total catch valued at about A$2 million.[9] The Tasmanian giant crab is very long-lived and slow-growing, making it vulnerable to overfishing.[7] Before export, they are sometimes kept alive in tanks with water that is 10–14 °C (50–57 °F).[3]

References

- Peter Davie (2010). "Pseudocarcinus gigas (Lamarck, 1818)". World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved October 9, 2010.

- Palomares, M. L. D. and Pauly, D., eds. (2013). "Pseudocarcinus gigas" in SeaLifeBase. December 2013 version.

- Levings, A.H. & P.C. Gill (2010). Seasonal Winds Drive Water Temperature Cycle and Migration Patterns of Southern Australian Giant Crab Pseudocarcinus gigas. In: G.H. Kruse, G.L. Eckert, R.J. Foy, R.N. Lipcius, B. Sainte-Marie, D.L. Stram, & D. Woodby (eds.), Biology and Management of Exploited Crab Populations under Climate Change. ISBN 978-1-56612-154-5. doi:10.4027/bmecpcc.2010.09

- P. K. L. Ng, D. Guinot & P. J. F. Davie (2008). "Systema Brachyurorum: Part I. An annotated checklist of extant Brachyuran crabs of the world" (PDF). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 17: 1–286.

- Poore, G.C.B. (2004). Marine Decapod Crustacea of Southern Australia: A Guide to Identification. CSIRO Publishing. p. 445. ISBN 0-643-06906-2.

- Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (12 February 2013). "Giant crab". ABC Hobart. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- D. R. Currie & T. M. Ward (2009). South Australian Giant Crab (Pseudocarcinus gigas) Fishery (PDF). South Australian Research and Development Institute. Fishery Assessment Report for PIRSA. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- N. Coleman (1991). Encyclopedia of Marine Animals. Blandford, Villiers House. p. 107. ISBN 0-7137-2289-4.

- "Giant crab fishery". Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. December 15, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

External links