Proto-Surrealism

Proto-Surrealism is a term used for Surrealism avant-la-lettre. It is the study of various forms of art, literature, and other mediums that correspond to, reference, or share similarities to the 20th-century art movement known as Surrealism. This definition is considered a controversial topic, with many debating the suitability of the term surrealism to describe these bodies of work and instead opting to use the term Fantastique or Fantastic Art.

Definition

Surrealism is a 20th-century art movement. André Breton, a French poet, known as one of the core founders of the Surrealist movement, wrote two manifestos that define surrealism.[2] Many current art critics and historians aim to identify characteristics which enable works of art to be categorized as surrealism. These identifying elements include automatism and a spirit of spontaneity, hyper-realistic dreamlike scenes, psychology and mythology as themes, a focus on dreams, psychoanalysis, fantastic imagery, a break from imagery, illogical juxtapositions, distorted figures, and personal iconography.[1] Proto-surrealism doesn't adhere to Breton's strict definition of surrealism and its guidelines.

15th – 17th century art

During the Late Renaissance and Baroque era there was a prevalence of artwork and imagery created that shared aspects of surrealism. In particular, the work of artists like Hieronymus Bosch and Giuseppe Arcimboldo are credited by modern surrealists as being influential to the surrealist movement.

Hieronymus Bosch

A Dutch artist during the late 15th and early 16th century, Hieronymus Bosch began his career following the direction of his family of painters.[3] It was here that he acquired the skills of a painter and began to gain favor from court patrons. During his lifetime, Bosch created numerous paintings and drawings, and while much of his work has been lost to history, the paintings and drawings recovered and attributed to Bosch by art historians show scenes that contain very surreal and fantastic imagery. As German art historian Hans Belting writes, "Ever since research on Hieronymus Bosch began, his paintings have captivated the imagination, exerting a fascination that has spawned an insatiable demand for ever new interpretations, none of them quite satisfactory." [4]

In Bosch's most famous work - the triptych "The Garden of Earthly Delights" - the three panels show scenes that depict Heaven, Earth, and Hell.[3] The far left panel showcases a scene from Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Here God stands between the two while an assortment of real and mythological creatures crawl out from a hole below. Above the trio, there is a building that sits in the middle of a lake while various other mythological creatures roam above and around the structure. In the midst, a fantastical landscape begins to melt into the background. The large middle panel shows a scene of numerous nude humans dancing, swimming, riding animals that are both real and mythical and suggestively cavorting.

Moving to back of the panel, there are many structures with fish-like creatures flying above them, humans and human-like beings in and around the structures, and other beings interacting around the space can be seen. Throughout this middle panel, there are gigantic birds, humans inside crustacean-like creatures, caves, and an assortment of other activities and objects in the scenes. However, the panel that Bosch is most likely remembered for is the far-right panel, depicting hell. This panel contains very detailed imagery; a large knife blade protrudes from between two massive ears of pig dressed in a nun's garments while attempting to kiss a man's cheek, a man's hollow body cavity merges with a tree, and a bird-like creature that appears to swallow humans whole while excreting its human waste into a pit of other fallen humans.

Behind all this action, there are crowds of naked bodies that disappear into an ominous red pool and cities that appear to be burning and melting into the dark and misty background. The vision is dark and violent. According to Dr. Nils Büttner, author of Hieronymus Bosch: Visions and Nightmares, this panel depicts a "prototype of everything we understand as Hell," and "Other people came up with images of Hell, but nothing so fantastic."[5]The erotic scenes, wild strange monsters, fantasy fruits, and illogical juxtapositions lead some art historians to credit Bosch as being the forefather of the surrealist movement.[6]

Bosch's Christ in Limbo, features another hell-like scene with a giant humanoid creature who guzzles humans whilst other mythological creatures roam about with various human interactions. to his drawing of The Listening Wood and the Seeing Field, an ink drawing which displays two ears in a forest and a field full of eyeballs as an owl sits in a hollow tree,[7] Bosch has a reputation of using fantastic imagery, mythology, and bizarre and hellish dreamlike scenes within his work. This theme that historians like Laurinda Dixon, have attributed to hallucinations caused by St. Anthony's Fire, a common disease of the time which occurred after consuming the parasitic ergot fungus sometimes found on rye bread. This eventually created a form of LSD.[8]

The surrealist qualities and elements found throughout much of Bosch's work have led some to title him as a proto-surrealist. In fact, in his first Surrealist Manifesto, Andre Breton dubbed Bosch as a forerunner to Surrealism, saying Bosch's work was "a strange marriage of fideism and revolt... the singer of the unconscious" and that his composition was "the example of automatic writing."[3]

Arguments against Hieronymus Bosch's title of Proto-Surrealist

Arguments against calling Bosch a proto-surrealist usually fall in line with art historian Walter Bosing's comments. Bosing writes in his book, Bosch, that "...the tendency to interpret Bosch's imagery in terms of modern Surrealism or Freudian psychology is anachronistic. We forget too often that Bosch never read Freud and that modern psychoanalysis would have been incomprehensible to the medieval mind... Modern psychology may explain the appeal Bosch's pictures have for us, but it cannot explain the meaning they had for Bosch and his contemporaries. Bosch did not intend to evoke the subconscious of the viewer, but to teach him certain moral and spiritual truths, and thus his images generally had a precise and premeditated significance."[9]

Giuseppe Arcimboldo

A 16th-century Italian court portraitist, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, has become the most famous in modern times for his composite portraits that utilize assortments of fruits, vegetables, animals, or every day objects to create personified portraits. His most famous painting, Vertumnus, utilizes an array of fruits and vegetables to create a portrait depicting Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor painted as Vertumnus, the Roman God of the seasons. Some art historians claim that much of Arcimboldo's composite portraiture, while comedic in some senses, was created in a larger sense to comment on various issues of the time. For example, in The Librarian, a composite portrait where a man's portrait is built out of books, historians argue this work was meant as a criticism of wealthy people who collected books only to own them, rather than to read them.[10] In other ways, art historian Benno Geiger, in his thorough analysis of Arcimboldo - I dipinti ghiribizzosi di Giuseppe Arcimboldi - writes that a line from a sonnet ("There's Neither Shape nor Form in it") reveals "the painter's secret intention, which was more that of a philosopher than a superficial glance might lead us to believe. His method was to cast a cloak of art over nature, that is, to present the truth by disguising it."[11] While his composite portraiture flourished under the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, his work was soon lost until the early 20th century when the Surrealist movement began to revive and take inspiration from his creations.[12] In fact during the 1930s, Alfred Barr, a famous American art historian, put him in a Museum of Modern Art exhibition, called Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism, in New York, and Salvador Dalí, a world-renowned surrealist painter, decided to honor Arcimboldo with the title of "father of Surrealism."[13]

Others

As historians look back through the various pieces of art created during the late Renaissance and Baroque era, they have begun to uncover more work that could be filed under the title of Proto-Surrealism. Below are a few examples of artists who produced work that could be labeled as proto-surrealist.

| Proto-Surrealist | Work |

|---|---|

| Pieter Huys |  The Temptation of St. Anthony [14] |

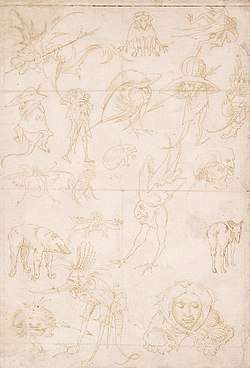

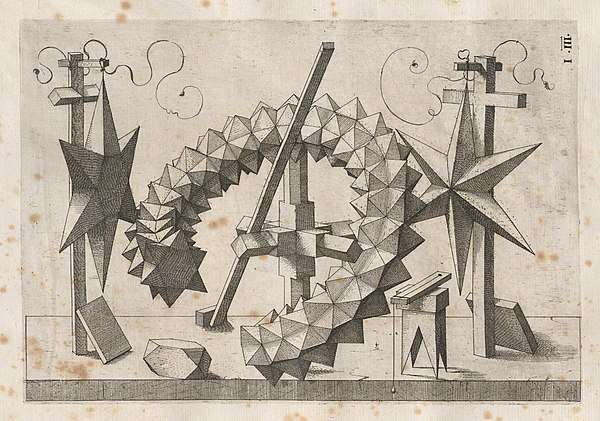

| Wenzel Jamnitzer |  Etching from Perspective Corporum Regularium 1568[15] |

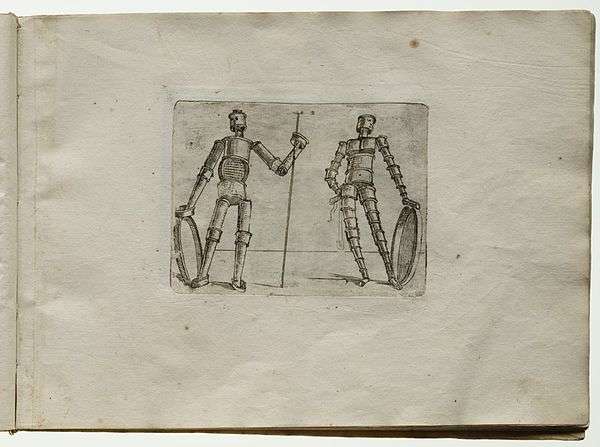

| Giovanni Battista Braccelli |  Bizzare di Varie Figure 44[16] |

| Pieter Breugel the Elder | .jpg) Temptation of Saint Anthony[17] |

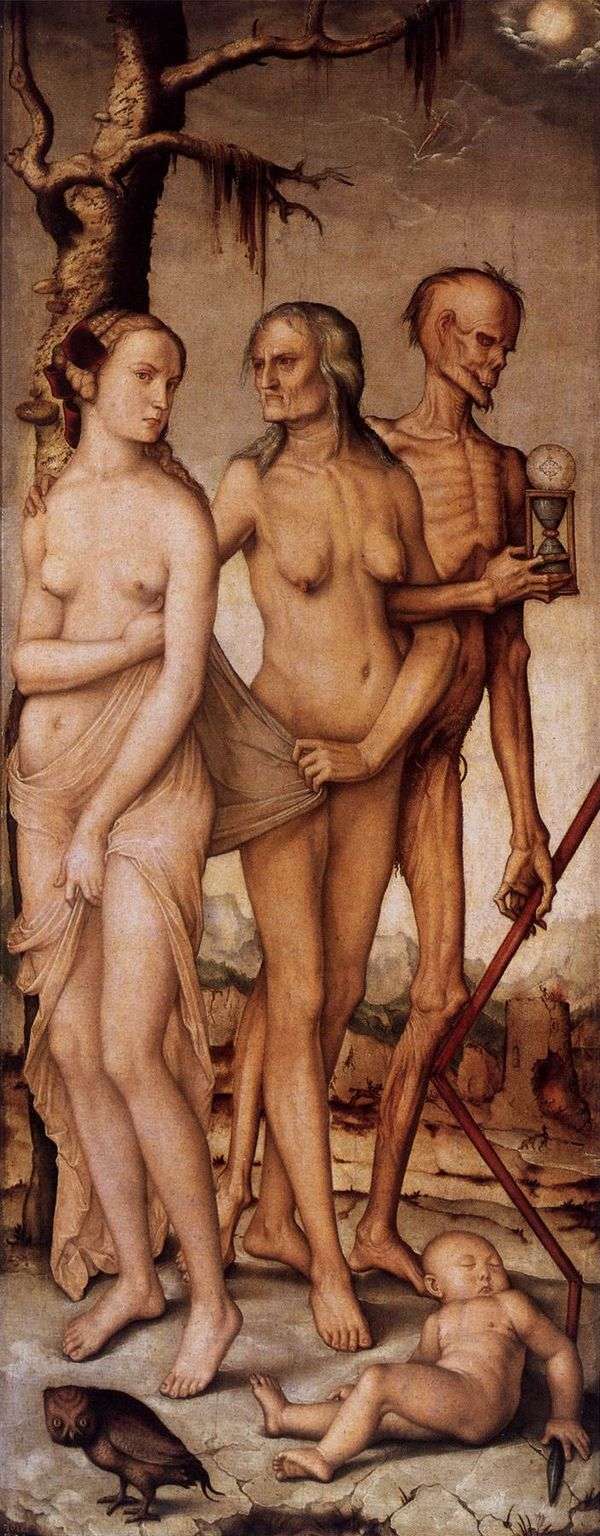

| Hans Baldung Grien |  The Ages of Woman and Death[18] |

| Joos de Momper |  From a series of four seasons in anthropomorphic landscapes: Allegory of Winter[19] |

Terminology Debate

In the end, Proto-Surrealism is a category of art that is up for debate. Apart from identifying obscure works of art, the categorization and terminology used leaves more questions than answers. Those who want to label this bizarre work as proto-surrealist soon begin to ask themselves the following questions:

- "How does one define Surrealism?"

- "Can you label certain "fantastique" art as surrealist if the artist didn’t study Freudian theory?"

- "If one agrees that certain fantastique art is to be considered surrealism, where is the line drawn?"

- "Is all surrealism fantastique work? Or is all fantastique work surrealism? Or is there an overlap?"

- "If there is an overlap how does one define that overlap area?"

- "Are Proto-Surrealists artists who surrealists draw inspiration from?"

- "Does one have to study Freud's psychoanalysis and utilize his studies in one's work in order to be considered a surrealist?"

- "Does the artists define his work as Surrealism or does the viewer?"

- "Who judges what is Surrealism and what is not? Is that the viewer's choice or that of the art critic?"

In WGBH Educational Foundation series "Studio Talk," Karl Fortress, Dennis E. Byng, and William Klenk offer discussion and debate over the topic of defining, in the episode entitled: Surrealism: Karl Fortress.[20]

References

- Craven, Jackie Craven Jackie; Writing, Doctor of Arts in; Architecture, Has Over 20 Years of Experience Writing About; decor, the arts She is the author of two books on home; Design, Sustainable; Poetry, A. Collection of Art-Themed. "These Artists Thrived on Dreams - Discover Their Surreal World". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- "André Breton | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- Cohen, Alina (2018-04-24). "Why Bosch Is Used to Describe Everything from High Fashion to Heavy Metal". Artsy. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- Belting, Hans (2016). Hieronymus Bosch - The Garden of Earthly Delights. Prestel. ISBN 978-3-7913-8205-0.

- Cohen, Alina (2018-04-24). "Why Bosch Is Used to Describe Everything from High Fashion to Heavy Metal". Artsy. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- "Hieronymous Bosch - The Complete Works - hieronymus-bosch.org". www.hieronymus-bosch.org. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- "The hearing forest and the sighted field by Hieronymus Bosch: History, Analysis & Facts". Arthive. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- "St. Anthony's Fire -- Ergotism". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2019-11-19.

- Bosing, Walter. (2000). Hieronymus Bosch, c. 1450-1516 : between heaven and hell. London: Taschen. ISBN 3822858560. OCLC 45329900.

- Elhard, K. C. (2005). "Reopening the Book on Arcimboldo's Librarian". Libraries & the Cultural Record. 40 (2): 115–127. doi:10.1353/lac.2005.0027. ISSN 1932-9555.

- "History of Art: Renaissance - Arcimboldo". www.all-art.org. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- Afterword (2011-01-18). "Giuseppe Arcimboldo: The prince of produce portraiture | National Post". Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- https://nationalpost.com/afterword/giuseppe-arcimboldo-the-prince-of-produce-portraiture

- "The Temptation of Saint Anthony". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- "Perspectiva Corporum Regularium,1568". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- "Причудливые узоры — Просмотр — Mировая цифровая библиотека". www.wdl.org. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- Ruddley, John; Foote, Timothy (April 1969). "The World of Bruegel c.1525-1569". Art Education. 22 (4): 29. doi:10.2307/3191348. ISSN 0004-3125. JSTOR 3191348.

- "The Ages of Woman and Death - The Collection". Museo Nacional del Prado. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- hoakley (2018-11-24). "The Four Seasons: Before Poussin". The Eclectic Light Company. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- "Studio Talk; Surrealism: Karl Fortress". American Archive of Public Broadcasting. Retrieved 2019-04-23.