Prothonotary warbler

The prothonotary warbler (Protonotaria citrea) is a small songbird of the New World warbler family. It is the only member of the genus Protonotaria.[2]

| Prothonotary warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Protonotaria Baird, 1858 |

| Species: | P. citrea |

| Binomial name | |

| Protonotaria citrea (Boddaert, 1783) | |

| |

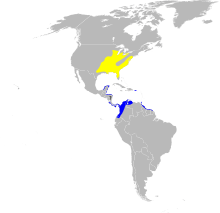

| Range of P. citrea Breeding range Wintering range | |

Taxonomy

The prothonotary warbler was described by the French polymath Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon in 1779 in his Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux from a specimen collected in Louisiana. Buffon coined the French name Le figuier protonotaire.[3] The bird was also illustrated in a hand-coloured plate engraved by François-Nicolas Martinet in the Planches Enluminées D'Histoire Naturelle which was produced under the supervision of Edme-Louis Daubenton to accompany Buffon's text.[4] Neither the plate caption nor Buffon's description included a scientific name but in 1783 the Dutch naturalist Pieter Boddaert coined the binomial name Motacilla citrea in his catalogue of the Planches Enluminées.[5] The prothonotary warbler is now the only species placed in the genus Protonotaria that was introduced in 1858 by the American naturalist Spencer Baird.[6][7] The species is monotypic, no subspecies are recognised.[7] The genus name is from Late Latin protonotarius, meaning "prothonotary", a notary attached to the Byzantine court who wore golden-yellow robes. The specific citrea is from Latin citreus meaning the colour "citrine".[8] It was once known as the golden swamp warbler.[9]

A molecular phylogenetic study of the family Parulidae published in 2010 found that the prothonotary warbler was a sister species to Swainson's warbler (Limnothlypis swainsonii).[10]

Description

The prothonotary warbler is 13 cm (5.1 in) long and weighs 12.5 g (0.44 oz). It has an olive back with blue-grey wings and tail, yellow underparts, a relatively long pointed bill, and black legs. The adult male has a bright orange-yellow head. Females and immature birds are duller and have a yellow head. In flight from below, the short, wide tail has a distinctive two-toned pattern, white at the base and dark at the tip.[11]

Distribution and habitat

It breeds in hardwood swamps in extreme southeastern Ontario and eastern United States. It winters in the West Indies, Central America and northern South America.[12] It is a rare vagrant to western states, most notably California.

Behavior and ecology

It is the only eastern warbler that nests in natural or artificial cavities, sometimes using old downy woodpecker holes. The male often builds several incomplete, unused nests in his territory; the female builds the real nest. It lays 3–7 eggs.

The preferred foraging habitat is dense, woody streams, where the prothonotary warbler forages actively in low foliage, mainly for insects and snails.

The song of this bird is a simple, loud, ringing sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet-sweet. The call is a loud, dry chip, like that of a hooded warbler. Its flight call is a loud seeep.[13]

Status

These birds are declining in numbers due to loss of habitat. They are also parasitized by the brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater), or outcompeted for nest sites by the house wren (Troglodytes aedon). It is listed as endangered in Canada. The species persists in protected environments such as South Carolina's Francis Beidler Forest, which is currently home to more than 2,000 pairs, the densest known population.[14]

In culture

The prothonotary warbler became known in the 1940s as the bird that, in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee, established a connection between Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss. Chambers had testified that Hiss enjoyed bird-watching, and once bragged about seeing a prothonotary warbler. Hiss later testified to the same incident, causing many members to become convinced of the pair's acquaintance.[15][16][17]

This bird is mentioned in A Sand County Almanac by Aldo Leopold as the "[J]ewel of my disease-ridden woodlot", "as proof that dead trees are transmuted into living animals, and vice versa. When you doubt the wisdom of this arrangement, take a look at the prothonotary." [18]

John James Audubon's painting of a prothonotary warbler is the third plate in his The Birds of America.

Kurt Vonneguts' novel Jailbird describes the warbler as "the only birds that are housebroken in captivity".

Gallery

In a cavity nest

In a cavity nest Painting by John James Audubon

Painting by John James Audubon.jpg) Painting by Robert Ridgway

Painting by Robert Ridgway

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Protonotaria citrea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curson, Jon; Quinn, David; Beadle, David (1994). New World Warblers. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 159–161. ISBN 0-7136-3932-6.

- Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc de (1779). "Le figuier protonotaire". Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux (in French). Volume 9. Paris: De L'Imprimerie Royale. p. 465.

- Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc de; Martinet, François-Nicolas; Daubenton, Edme-Louis; Daubenton, Louis-Jean-Marie (1765–1783). "Figuier à ventre et tête jaunes de la Loisiane". Planches Enluminées D'Histoire Naturelle. Volume 8. Paris: De L'Imprimerie Royale. Plate 704 Fig. 2.

- Boddaert, Pieter (1783). Table des planches enluminéez d'histoire naturelle de M. D'Aubenton : avec les denominations de M.M. de Buffon, Brisson, Edwards, Linnaeus et Latham, precedé d'une notice des principaux ouvrages zoologiques enluminés (in French). Utrecht. p. 38, Number 704 Fig. 2.

- Baird, Spencer F. (1858). Reports of explorations and surveys to ascertain the most practical and economical route for a railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean made under the direction of the secretary of war in 1853-1856. Volume 9 Birds. Washington: Printed by Beverly Tucker. pp. xix, xxxi, 235, 239.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2019). "New World warblers, mitrospingid tanagers". IOC World Bird List Version 9.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 109, 318. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Bird: The definitive visual guide. DK Publishing. 2007.

- Lovette, I.J.; Pérez-Emán, J.L.; Sullivan, J.P.; Banks, R.C.; Fiorentino, I.; Córdoba-Córdoba, S.; Echeverry-Galvis, M.; Barker, F.K.; Burns, K.J.; Klicka, J.; Lanyon, S.M.; Bermingham, E. (2010). "A comprehensive multilocus phylogeny for the wood-warblers and a revised classification of the Parulidae (Aves)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 57 (2): 753–770. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.07.018.

- Dunne, Pete (2006). Pete Dunne's Essential Field Guide Companion. Houghton Mifflin.

- Stiles, Gary; Skutch, Alexander (1989). A Guide to the Birds of Costa Rica. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9600-4.

- Alderfer, Jonathan (2006). National Geographic Complete Birds of North America. National Geographic Society.

- "BirdWatching:Francis Beidler Forest, Harleyville, South Carolina". Feb 15, 2013.

- Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. Random House. pp. 362, 564, 572, 573, 580. ISBN 0-89526-571-0.

- Linder, Doug (2003). "The Trials of Alger Hiss: A Commentary". Famous Trials. University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. Archived from the original on 2006-08-30.

- Miller, John J. (30 April 2007). "The Unsung Hero of the Cold War". National Review. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012.

- Aldo Leopold (1996). A Sand County Almanac. The Random House Publishing Group. p. 82.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Protonotaria citrea. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Protonotaria citrea |

- "Prothonotary warbler media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Prothonotary warbler Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Prothonotary warbler - Protonotaria citrea - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Prothonotary Warbler "The Swamp Songster" by Lisa Petit (January 1997) – Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center

- Prothonotary warbler recording at Florida Museum of Natural History

- Prothonotary warbler photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Prothonotary warbler species account at Neotropical Birds (Cornell Lab of Ornithology)