Projector

A projector or image projector is an optical device that projects an image (or moving images) onto a surface, commonly a projection screen. Most projectors create an image by shining a light through a small transparent lens, but some newer types of projectors can project the image directly, by using lasers. A virtual retinal display, or retinal projector, is a projector that projects an image directly on the retina instead of using an external projection screen.

The most common type of projector used today is called a video projector. Video projectors are digital replacements for earlier types of projectors such as slide projectors and overhead projectors. These earlier types of projectors were mostly replaced with digital video projectors throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, but old analog projectors are still used at some places. The newest types of projectors are handheld projectors that use lasers or LEDs to project images. Their projections are hard to see if there is too much ambient light.

Movie theaters used a type of projector called a movie projector, nowadays mostly replaced with digital cinema video projectors.

Different projector types

Projectors can be roughly divided into three categories, based on the type of input. Some of the listed projectors were capable of projecting several types of input. For instance: video projectors were basically developed for the projection of prerecorded moving images, but are regularly used for still images in PowerPoint presentations and can easily be connected to a video camera for real-time input. The magic lantern is best known for the projection of still images, but was capable of projecting moving images from mechanical slides since its invention and was probably at its peak of popularity when used in phantasmagoria shows to project moving images of ghosts.

Real-time

- Camera obscura

- Concave mirror

- Opaque projector

- Overhead projector

- Document camera

Still images

- slide projector

- magic lantern

- magic mirror

- steganographic mirror (see below for details)

- enlarger (not for direct viewing, but for the production of photographic prints)

Moving images

- movie projector

- video projector

- handheld projector

- virtual retinal display

- trotting horse lamp (see below for details)

History

There probably existed quite a few other types of projectors than the examples described below, but evidence is scarce and reports are often unclear about their nature. Spectators not always provided the details needed to differentiate between for instance a shadow play and a lantern projection. Many did not understand the nature of what they had seen and few had ever seen other comparable media. Projections were often presented or perceived as magic or even as religious experiences, with most projectionists unwilling to share their secrets. Joseph Needham sums up some possible projection examples from China in his 1962 book series Science and Civilization in China[1]

Prehistory to 1100

Shadow play

The earliest projection of images was most likely done in primitive shadowgraphy dating back to prehistory. Shadow play usually does not involve a projection device, but can be seen as a first step in the development of projectors. It evolved into more refined forms of shadow puppetry in Asia, where it has a long history in Indonesia (records relating to Wayang since 840 CE), Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, China (records since around 1000 CE), India and Nepal.

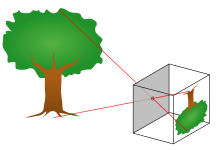

Camera obscura

Projectors share a common history with cameras in the camera obscura. Camera obscura (Latin for "dark room") is the natural optical phenomenon that occurs when an image of a scene at the other side of a screen (or for instance a wall) is projected through a small hole in that screen to form an inverted image (left to right and upside down) on a surface opposite to the opening. The oldest known record of this principle is a description by Han Chinese philosopher Mozi (ca. 470 to ca. 391 BC). Mozi correctly asserted that the camera obscura image is inverted because light travels in straight lines.

In the early 11th century, Arab physicist Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) described experiments with light through a small opening in a darkened room and realized that a smaller hole provided a sharper image.

The use of a lens in the opening of a wall or closed window shutter of a darkened room has been traced back to circa 1550. The shared history of camera and projector basically split with the introduction of the magic lantern in the later half of the 17th century. The camera obscura device would mostly live on as a drawing aid in the form of tents and boxes and was adapted into the photographic camera in the first decades of the 19th century.

Chinese magic mirrors

The oldest known objects that can project images are Chinese magic mirrors. The origins of these mirrors have been traced back to the Chinese Han dynasty (206 BC – 24 AD)[2] and are also found in Japan. The mirrors were cast in bronze with a pattern embossed at the back and a mercury amalgam laid over the polished front. The pattern seen on the back of the mirror is seen in a projection when light is reflected from the polished front onto a wall or other surface. No trace of the pattern can be discerned on the reflecting surface with the naked eye, but minute undulations on the surface are introduced during the manufacturing process and cause the reflected rays of light to form the pattern.[3] It is very likely that the practice of image projection via drawings or text on the surface of mirrors predates the very refined ancient art of the magic mirrors, but no evidence seems to be available.

Revolving lanterns

Revolving lanterns have been known in China as "trotting horse lamps" [走馬燈] since before 1000 CE. A trotting horse lamp is a hexagonal, cubical or round lantern which on the inside has cut-out silhouettes attached to a shaft with a paper vane impeller on top, rotated by heated air rising from a lamp. The silhouettes are projected on the thin paper sides of the lantern and appear to chase each other. Some versions showed some extra motion in the heads, feet and/or hands of figures by connecting them with a fine iron wire to an extra inner layer that would be triggered by a transversely connected iron wire.[4] The lamp would typically show images of horses and horse-riders.

In France similar lanterns were known as "lanterne vive" (bright or living lantern) in Medieval times and "lanterne tournante" since the 18th century. An early variation was described in 1584 by Jean Prevost in his small octavo book La Premiere partie des subtiles et plaisantes inventions. In his "lanterne" cut-out figures of a small army were placed on wooden platform rotated by a cardboard propeller above a candle. The figures cast their shadows on translucent, oiled paper on the outside of the lantern. He suggested to take special care that the figures look lively: with horses raising their front legs as if they were jumping and soldiers with drawn swords, a dog chasing a hare, etcetera. According to Prevost barbers were skilled in this art and it was common to see these night lanterns in their shop windows. A more common version had the figures, usually representing grotesque or devilish creatures, painted on a transparent strip. The strip was rotated inside a cylinder by a tin impeller above a candle. The cylinder could be made of paper or of sheet metal perforated with decorative patterns. Around 1608 Mathurin Régnier mentioned the device in his Satire XI as something used by a patissier to amuse children.[5] Régnier compared the mind of an old nagger with the lantern's effect of birds, monkeys, elephants, dogs, cats, hares, foxes and many strange beasts chasing each other.[6]

John Locke (1632-1704) referred to a similar device when wondering if ideas are formed in our minds at regular intervals,"not much unlike the images in the inside of a lantern, turned round by the heat of a candle." Related constructions were used as Christmas decorations in England [7] and parts of Europe. A common type of rotating device that is closely related does not really involve light and shadows, but it simply uses candles and an impeller to rotate a platform with tiny wooden figurines.

Most modern electric versions of this type of lantern use all kinds of colorful transparent cellophane figures which are projected across the walls, especially popular for nurseries.

1100 to 1500

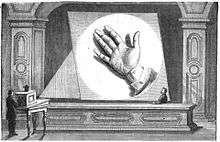

Concave mirrors

The inverted real image of an object reflected by a concave mirror can appear at the focal point in front of the mirror.[8] In a construction with an object at the bottom of two opposing concave mirrors (parabolic reflectors) on top of each other, the top one with an opening in its center, the reflected image can appear at the opening as a very convincing 3D optical illusion.[9]

The earliest description of projection with concave mirrors has been traced back to a text by French author Jean de Meun in his part of Roman de la Rose (circa 1275).[10] A theory known as the Hockney-Falco thesis claims that artists used either concave mirrors or refractive lenses to project images onto their canvas/board as a drawing/painting aid as early as circa 1430.[11]

It has also been thought that some encounters with spirits or gods since antiquity may have been conjured up with (concave) mirrors.[12]

Fontana's lantern

_giovanni_da_fontana_(probably)_-_apparentia_nocturna_ad_terrorem_videntiumR.jpg)

Around 1420 the Venetian scholar and engineer Giovanni Fontana included a drawing of a person with a lantern projecting an image of a demon in his book about mechanical instruments "Bellicorum Instrumentorum Liber".[13] The Latin text "Apparentia nocturna ad terrorem videntium" (Nocturnal appearance to frighten spectators)" clarifies its purpose, but the meaning of the undecipherable other lines is unclear. The lantern seems to simply have the light of an oil lamp or candle go through a transparent cylindrical case on which the figure is drawn to project the larger image, so it probably couldn't project an image as clearly defined as Fontana's drawing suggests.

Possible 15th century image projector

In 1437 Italian humanist author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher and cryptographer Leon Battista Alberti is thought to have possibly projected painted pictures from a small closed box with a small hole, but it is unclear whether this actually was a projector or rather a type of show box with transparent pictures illuminated from behind and viewed through the hole.[14]

1500 to 1700

16th to early 17th century

Leonardo da Vinci is thought to have had a projecting lantern - with a condensing lens, candle and chimney - based on a small sketch from around 1515.[15]

In his Three Books of Occult Philosophy (1531-1533) Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa claimed that it was possible to project "images artificially painted, or written letters" onto the surface of the moon with the means of moonbeams and their "resemblances being multiplied in the air". Pythagoras would have often performed this trick.[16]

In 1589 Giambattista della Porta published about the ancient art of projecting mirror writing in his book Magia Naturalis.[17][18]

Dutch inventor Cornelis Drebbel, who is a likely inventor of the microscope, is thought to have had some kind of projector that he used in magical performances. In a 1608 letter he described the many marvelous transformations he performed and the apparitions that he summoned by the means of his new invention based on optics. It included giants that rose from the earth and moved all their limbs very lifelike.[19] The letter was found in the papers of his friend Constantijn Huygens, father of the likely inventor of the magic lantern Christiaan Huygens.

Helioscope

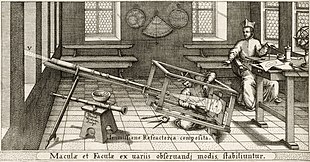

In 1612 Italian mathematician Benedetto Castelli wrote to his mentor, the Italian astronomer, physicist, engineer, philosopher and mathematician Galileo Galilei about projecting images of the sun through a telescope (invented in 1608) to study the recently discovered sunspots. Galilei wrote about Castelli's technique to the German Jesuit priest, physicist and astronomer Christoph Scheiner.[20]

From 1612 to at least 1630 Christoph Scheiner would keep on studying sunspots and constructing new telescopic solar projection systems. He called these "Heliotropii Telioscopici", later contracted to helioscope.[20]

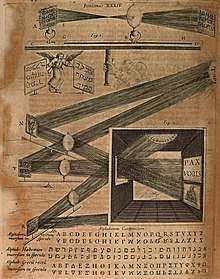

Steganographic mirror

The 1645 first edition of German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher's book Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae included a description of his invention, the steganographic mirror: a primitive projection system with a focusing lens and text or pictures painted on a concave mirror reflecting sunlight, mostly intended for long distance communication. He saw limitations in the increase of size and diminished clarity over a long distance and expressed his hope that someone would find a method to improve on this.[21] Kircher also suggested projecting live flies and shadow puppets from the surface of the mirror.[22] The book was quite influential and inspired many scholars, probably including Christiaan Huygens who would invent the magic lantern. Kircher was often credited as the inventor of the magic lantern, although in his 1671 edition of Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae Kircher himself credited Danish mathematician Thomas Rasmussen Walgensten for the magic lantern, which Kircher saw as a further development of his own projection system.[23][24]

Although Athanasius Kircher claimed the Steganographic mirror as his own invention and wrote not to have read about anything like it,[24] it has been suggested that Rembrandt's 1635 painting of "Belshazzar's Feast" depicts a steganographic mirror projection with God's hand writing Hebrew letters on a dusty mirror's surface.[25]

In 1654 Belgian Jesuit mathematician André Tacquet used Kircher's technique to show the journey from China to Belgium of Italian Jesuit missionary Martino Martini.[26] It is sometimes reported that Martini lectured throughout Europe with a magic lantern which he might have imported from China, but there's no evidence that anything other than Kircher's technique was used.

Magic lantern

By 1659 Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens had developed the magic lantern, which used a concave mirror to reflect and direct as much of the light of a lamp as possible through a small sheet of glass on which was the image to be projected, and onward into a focusing lens at the front of the apparatus to project the image onto a wall or screen (Huygens apparatus actually used two additional lenses). He did not publish nor publicly demonstrate his invention as he thought it was too frivolous and was ashamed about it.

The magic lantern became a very popular medium for entertainment and educational purposes in the 18th and 19th century. This popularity waned after the introduction of cinema in the 1890s. The magic lantern remained a common medium until slide projectors came into widespread use during the 1950s.

1700 to 1900

Solar microscope

A few years before his death in 1736 Polish-German-Dutch physicist Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit reportedly constructed a solar microscope, which basically was a combination of the compound microscope with camera obscura projection. It needed bright sunlight as a light source to project a clear magnified image of transparent objects. Fahrenheit's instrument may have been seen by German physician Johann Nathanael Lieberkühn who introduced the instrument in England, where optician John Cuff improved it with a stationary optical tube and an adjustable mirror.[27] In 1774 English instrument maker Benjamin Martin introduced his "Opake Solar Microscope" for the enlarged projection of opaque objects. He claimed:

The Opake Microsc[o]pe, not only magnifies the natural Appearance or Size of Objects of every Sort, but at the ſame time throws ſuch a Quantity of Solar Rays upon them, as to make all their Colours appear vaſtly more vivid and ſtrong than to the naked Eye; and their Parts ſo expanded and diſtinct upon a fixed Screen, that they are not only viewed with the utmoſt Pleaſure, but may be drawn with the greateſt Eaſe by any ingenious Hand."[28]

Opaque projectors

Swiss mathematician, physicist, astronomer, logician and engineer Leonhard Euler demonstrated an opaque projector, now commonly known as an episcope, around 1756. It could project a clear image of opaque images and (small) objects.[29] French scientist Jacques Charles is thought to have invented the similar "megascope" in 1780. He used it for his lectures.[30] Around 1872 Henry Morton used an opaque projector in demonstrations for huge audiences, for example in the Philadelphia Opera House which could seat 3500 people. His machine did not use a condenser or reflector, but used an oxyhydrogen lamp close to the object in order to project huge clear images.[31]

20th century to present day

In the early and middle parts of the 20th century, low-cost opaque projectors were produced and marketed as a toy for children. The light source in early opaque projectors was often limelight, with incandescent light bulbs and halogen lamps taking over later. Episcopes are still marketed as artists’ enlargement tools to allow images to be traced on surfaces such as prepared canvas.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, overhead projectors began to be widely used in schools and businesses. The first overhead projector was used for police identification work. It used a cellophane roll over a 9-inch stage allowing facial characteristics to be rolled across the stage. The U.S. Army in 1945 was the first to use it in quantity for training as World War II wound down.

From the 1950s to the 1990s slide projectors for 35 mm photographic positive film slides were common for presentations and as a form of entertainment; family members and friends would occasionally gather to view slideshows, typically of vacation travels.

In the early 2000s, slides were largely replaced by digital images.

See also

Notes and references

- Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in China, vol. IV, part 1: Physics and Physical Technology (PDF). pp. 122–124. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-03. Retrieved 2016-08-30.

- Mak, Se-yuen; Yip, Din-yan (2001). "Secrets of the Chinese magic mirror replica". Physics Education. 36 (2): 102–107. Bibcode:2001PhyEd..36..102M. doi:10.1088/0031-9120/36/2/302.

- "Oriental magic mirrors and the Laplacian image" Archived 2014-12-19 at the Wayback Machine by Michael Berry, Eur. J. Phys. 27 (2006) 109–118, DOI: 10.1088/0143-0807/27/1/012

- Yongxiang Lu (2014-10-20). A History of Chinese Science and Technology, Volume 3. pp. 308–310. ISBN 9783662441633. Archived from the original on 2016-10-22.

- Laurent Mannoni Le grand art de la lumiere et de l'ombre (1995) p. 37-38

- "Les satyres et autres oeuvres de regnier avec des remarques". 1730.

- S. Alexander Locke's Lantern in Mind (1929)

- skullsinthestars (17 April 2014). "Physics demonstrations: The Phantom Lightbulb". Archived from the original on 18 January 2017.

- "PhysicsLAB: Demonstration: Real Images". Archived from the original on 2017-02-02.

- "Rose -". Archived from the original on 2016-09-16.

- "Art Optics -". Archived from the original on 2016-09-11.

- Ruffles, Tom (2004-09-27). Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife. pp. 15–17. ISBN 9780786420056. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07.

- Fontana, Giovanni (1420). "Bellicorum instrumentorum liber". p. 144. Archived from the original on 2016-09-18.

- "Camera Obscura - Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 2016-10-22.

- "The History of The Discovery of Cinematography - 1400 - 1599". Archived from the original on 2018-01-31.

- Agrippa (1993). Three Books of Occult Philosophy. ISBN 9780875428321. Archived from the original on 2017-09-21.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-07-21. Retrieved 2017-09-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Natural magick". 1658.

- Drebbel, Cornelis (1608). "brief aan Ysbrandt van Rietwijck" (PDF) (in Dutch). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-10-05.

- Whitehouse, David (2004). The Sun: A Biography. ISBN 9781474601092. Archived from the original on 2016-10-05.

- Kircher, Athanasius (1645). Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae. p. 912. Archived from the original on 2017-09-12.

- Gorman, Michael John (2007). Inside the Camera Obscura (PDF). p. 44. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-12-22.

- Rendel, Mats. "about Athanasius Kircher". Archived from the original on 2008-02-20.

- Rendel, Mats. "About the Construction of The Magic Lantern, or The Sorcerers Lamp". Archived from the original on 2016-03-27.

- Vermeir, Koen (2005). The magic of the magic lantern (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-12-20.

- "De zeventiende eeuw. Jaargang 10" (in Dutch and Latin). Archived from the original on 2017-09-04.

- S. Bradbury (2014). The Evolution of the Microscope. pp. 152–160. ISBN 9781483164328. Archived from the original on 2017-01-16.

- Martin, Benjamin (1774). The Description and Use of an Opake Solar Microscope. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01.

- Euler, Leonhard (1773). Briefe an eine deutsche Prinzessinn über verschiedene Gegenstände aus der Physik und Philosophie - Zweyter Theil (in German). pp. 192–196. Archived from the original on 2017-01-16.

- Hankins, Silverman (2014). Instruments and the Imagination. ISBN 9781400864119. Archived from the original on 2017-01-16.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Moigno's, François (1872). L'art des projections. Archived from the original on 2018-02-09.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Projectors. |