Procurement

Procurement is the process of finding and agreeing to terms, and acquiring goods, services, or works from an external source, often via a tendering or competitive bidding process.[1]

Procurement generally involves making buying decisions under conditions of scarcity. If sound data is available, it is good practice to make use of economic analysis methods such as cost-benefit analysis or cost-utility analysis.

Procurement is used to ensure the buyer receives goods, services, or works at the best possible price when aspects such as quality, quantity, time, and location are compared.[2] Corporations and public bodies often define processes intended to promote fair and open competition for their business while minimizing risks such as exposure to fraud and collusion.

Almost all purchasing decisions include factors such as delivery and handling, marginal benefit, and price fluctuations.

History

Formalized acquisition of goods and services has its roots in Military logistics, where the ancient practice of foraging and looting was taken up by professional quartermasters, a term which dates from the 17th Century. The first written records of what would be recognized now as the purchasing department of an industrial operation is in the railway companies of the 19th Century.

"The intelligence and fidelity exercised in the purchase, care and use of railway supplies influences directly the cost of construction and operating and affect the reputations of officers and the profits of owners."[3]

An early reference book from 1922 explains that

"The modern purchasing agent is a more important man [sic] by far than he was in older days when purchasing agents were likely to be rubber stamps or bargainers for an extra penny.A Purchasing agent of the modern breed is a creative thinker and planner and now regards his work as a profession"[4]

Overview

An important distinction should be made between analyses without risk and those with risk. Where risk is involved, either in the costs or the benefits, the concept of best value should be employed.

Procurement activities are also often split into two distinct categories, direct and indirect spend. Direct spend refers to the production-related procurement that encompasses all items that are part of finished products, such as raw material, components and parts. Direct procurement, which is the focus in supply chain management, directly affects the production process of manufacturing firms. In contrast, indirect procurement concerns non-production-related acquisition: obtaining "operating resources" which a company purchases to enable its operations. Indirect procurement comprises a wide variety of goods and services, from standardized items like office supplies and machine lubricants to complex and costly products and services like heavy equipment, consulting services, and outsourcing services.[5][6]

| Direct procurement and indirect procurement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types | ||||

| Direct procurement | Indirect procurement | |||

| Raw material and production goods | Maintenance, repair, and operating supplies, outsourcing | Capital goods and services | ||

|

F E A T U R E S |

Quantity | Large | Low | Low |

| Frequency | High | Relatively high | Low | |

| Value | Industry-specific | Low | High | |

| Nature | Operational | Tactical | Strategic | |

| Examples | Crude oil in petroleum industry | Lubricants, spare parts | Crude oil storage facilities | |

Topics

Procurement vs. sourcing vs. acquisition

Procurement is one component of the broader concept of sourcing and acquisition. Typically procurement is viewed as more tactical in nature (the process of physically buying a product or service) and sourcing and acquisition are viewed as more strategic and encompassing.

The Institute of Supply Management (ISM)[7] defines strategic sourcing as the process of identifying sources that could provide needed products or services for the acquiring organization. The term procurement is used to reflect the entire purchasing process or cycle, and not just the tactical components. ISM defines procurement as an organizational function that includes specifications development, value analysis, supplier market research, negotiation, buying activities, contract administration, inventory control, traffic, receiving and stores. Purchasing refers to the major function of an organization that is responsible for acquisition of required materials, services and equipment.

The United States Defense Acquisition University (DAU) defines procurement as the act of buying goods and services for the government.[8] DAU defines acquisition as the conceptualization, initiation, design, development, test, contracting, production, deployment, Logistics Support (LS), modification, and disposal of weapons and other systems, supplies, or services (including construction) to satisfy Department of Defense needs, intended for use in or in support of military missions.[8]

Acquisition and sourcing are therefore much wider concepts than procurement.

Multiple sourcing business models exist, and acquisition models exist.

Acquisition process

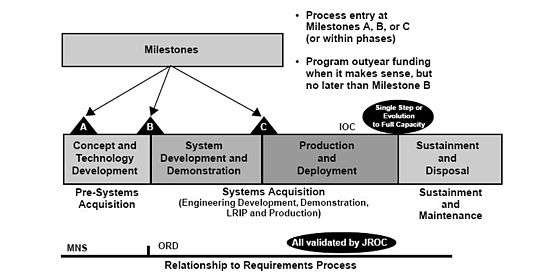

The revised acquisition process for major systems in industry and defense is shown in the next figure. The process is defined by a series of phases during which technology is defined and matured into viable concepts, which are subsequently developed and readied for production, after which the systems produced are supported in the field.[9]

The process allows for a given system to enter the process at any of the development phases. For example, a system using unproven technology would enter at the beginning stages of the process and would proceed through a lengthy period of technology maturation, while a system based on mature and proven technologies might enter directly into engineering development or, conceivably, even production. The process itself includes four phases of development:[9]

- Concept and technology development is intended to explore alternative concepts based on assessments of operational needs, technology readiness, risk, and affordability.

- The concept and technology development phase begins with concept exploration. During this stage, concept studies are undertaken to define alternative concepts and to provide information about capability and risk that would permit an objective comparison of competing concepts.

- The system development and demonstration phase could be entered directly as a result of a technological opportunity and urgent user need, as well as having come through concept and technology development.

- The last, and longest phase is the sustainable and disposal phase of the program. During this phase all necessary activities are accomplished to maintain and sustain the system in the field in the most cost-effective manner possible.

Sourcing business model

Procurement officials increasingly realize that their make-buy supplier decisions fall along a continuum from simple buying transactions to more complex, strategic buyer-supplier collaborations. It is important for procurement officials to use the right sourcing business model that fits each buyer-seller situation. There are seven models along the sourcing continuum: basic provider, approved provider, preferred provider, performance-based/managed services model, vested business model, shared services model and equity partnerships.

- A basic provider model is transaction-based; it usually has a set price for individual products and services for which there are a wide range of standard market options. Typically these products or services are readily available, with little differentiation in what is offered.

- An approved provider model uses a transaction-based approach where goods and services are purchased from prequalified suppliers that meet certain performance or other selection criteria.

- The preferred provider model also uses a transaction-based economic model, but a key difference between the preferred provider and the other transaction-based models is that the buyer has chosen to move to a supplier relationship where there is an opportunity for the supplier to add incremental value to the buyer's business to meet strategic objectives.

- A performance-based (or managed services model) is generally a formal, longer-term supplier agreement that combines a relational contracting model with an output-based economic model. It seeks to drive supplier accountability for output-based service-level agreements (SLAs) and/or cost reduction targets.

- A vested sourcing business model is a hybrid relationship that combines an outcome-based economic model with a relational contracting model. Companies enter into highly collaborative arrangements designed to create and share value for buyers and suppliers above and beyond.

- A shared services model is typically an internal organization based on an arm's-length outsourcing arrangement. Using this approach, processes are often centralized into an SSO that charges business units or users for the services they use.

- An equity partnership creates a legally binding entity; it can take different legal forms, from buying a supplier (an acquisition), to creating a subsidiary, to equity-sharing joint ventures or entering into cooperative (co-op) arrangements.

Procurement software

Procurement software (often labeled as e-procurement software) manages the purchasing processes electronically or via cloud computing.

Procurement life cycle

Most of the organizations think of their procurement process in terms of a life cycle. Different consulting firms and experts have developed various frameworks. Some of the most common steps from the most popular frameworks include:

- Identification of need and requirements analysis is an internal step that involves an understanding of business objectives by establishing a short term strategy (three to five years) for overall spend category followed by defining the technical direction and requirements.

- External macro-level market analysis: Once an organization understands its requirements, it should look outward to assess the overall marketplace. A key part of a market analysis is understanding the overall competitiveness of the marketplace and trends that are likely to impact the organization.

- Cost analysis is the accumulation, examination and manipulation of cost data for comparisons and projections. A cost analysis is important to help an organization make a make-buy decision.

- Supplier identification includes identifying particular suppliers that can provide the required product or services. There are many sources to search for potential suppliers. One good source is trade shows. Modern procurement software often incorporates a supplier catalog for standardized goods and services.

- Non-disclosure agreement (NDA): It is quite normal to request vendors to sign an NDA prior to engaging with them. This protects the organisation where sensitive information is shared with multiple potential vendors ahead of releasing detailed requirements which often point to strategic decisions a firm has taken.

- Supplier communication: When one or more suitable suppliers have been identified, an organization will typically conduct a competitive bidding process. Organizations can use a variety of competitive bidding methods including requests for quotation, requests for proposals, requests for information, requests for tender, request for solution or a request for partnership. Some institutions choose to use a notification service in order to raise the competition for the chosen opportunity. These systems can either be direct from their e-tendering software, or as a re-packaged notification from an external system. During this step direct contact may be made with the suppliers. References for product/service quality are consulted, and any requirements for follow-up services including installation, maintenance, and warranty are investigated. Samples of the product/service being considered may be examined, or trials undertaken. Organizations should do a risk assessment, total cost of ownership analysis and best value assessment before selecting the final suppliers/solution.

- Negotiations and contracting: Negotiations are undertaken that often include price, availability, customization, and delivery schedules. The details are outlined in a purchase order or more formal contract.

- Logistics and performance management: Supplier preparation, expediting, shipment, delivery, and payment for the product/service are completed, based on contract terms. Installation and training may also be included. An organization should evaluate the performance of the product/service as they are consumed. A supplier scorecard is a popular tool for this purpose. When the product/service has been consumed or disposed of, the contract expires, or the product or service is to be re-ordered, the organization should review their experience with the product/service. If the product/service is to be re-ordered, the company determines whether to consider other suppliers or to continue with the same supplier.

- Supplier management and liaison: Organizations that have more strategic goods or services that require ongoing interfaces with a supplier will use a supplier relationship management process. Strategic outsourcing relationships should set up formal governance processes.

Procurement performance

The Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply (CIPS) promotes a model of "five rights", which it suggests are "a traditional formula expressing the basic objectives of procurement and the general criteria by which procurement performance is measured", namely that goods and services purchased should be of the right quality, in the right quantity, delivered to the right place at the right time and obtained at the right price.[10] CIPS has in the past also offered an alternative listing of the five rights as "buy[ing] goods or services of the right quality, in the right quantity, from the right source, at the right time and at the right price.[11] Right source is added as a sixth right in CIPS' 2018 publication, Contract Administration.[12]

Ardent Partners published a report in 2011 which presented a comprehensive, industry-wide view into what was happening in the world of procurement at that time by drawing on the experience, performance, and perspective of nearly 250 chief procurement officers and other procurement executives. The report includes the main procurement performance and operational benchmarks that procurement leaders use to gauge the success of their organizations. This report found that the average procurement department manages 60.6% of total enterprise spend. This measure, commonly called "spend under management", refers to the percentage of total enterprise spend (which includes all direct and indirect spend) that a procurement organization manages or influences. Alternatively, the term may refer to the percentage of addressable spend which is influenced by procurement, "addressable spend" being the expenditure which could potentially be influenced.[13] The average procurement department also achieved an annual savings of 6.7% in the last reporting cycle, sourced 52.6% of its addressable spend, and has a contract compliance rate of 62.6%.[14]

Relationship with Finance

Procurement and Finance have, as functions within the corporate structure, been at odds. The contentious nature of their relationship can perhaps be attributed to the history of procurement itself. Historically, Procurement has been considered Finance's underling. One reason behind this perception can be ascribed to semantics. When Procurement was in its infancy, it was referred to as a "commercial" operation. And so the procurement department was referred to as the commercial department rather than the procurement department: the word "commercial" was understood to be associated with money. And so it was obvious that Procurement would become directly answerable to Finance. Another factor, equally grounded in semantics, was that procurement departments (or rather, commercial departments) were always seen as "spending the money". This impression was enough to situate Procurement within the Finance function.[15] It's easy to see why Procurement and Finance are functions with interests that are mutually irreconcilable. Whereas Procurement is fundamentally concerned with the spending or disbursal of money, Finance, by its very nature, performs a cost-cutting role. That is fundamentally the reason why Procurement's aspirations have been constantly checked by Finance's cost-cutting imperatives.[16] This notion, however, has been changing as more chief procurement officers have begun to argue for more autonomy and less interference from Finance departments.

Public procurement

Public procurement generally is an important sector of the economy. In Europe, public procurement accounted for 16.3% of the Community GDP in 2013.[17]

Public procurement

In public procurement (PP), contracting authorities and entities take environmental issues into account when tendering for goods or services. The goal is to reduce the impact of the procurement on human health and the environment.[18]

In the European Union, the Commission has adopted its communication on public procurement for a better environment, where proposes a political target of 50% Green public procurement to be reached by the Member States by the year 2010.[19] The European Commission has recommended GPP criteria for 21 product/service groups which may be used by any public authority in Europe.[20]

PP can be applied to contracts both above and below the threshold for application of the Procurement Directives. The 2014 Procurement Directives enable public authorities to take environmental considerations into account. This applies during pre-procurement, as part of the procurement process itself, and in the performance of the contract. Rules regarding exclusion and selection aim to ensure a minimum level of compliance with environmental law by contractors and sub-contractors. Techniques such as life-cycle costing, specification of sustainable production processes, and use of environmental award criteria are available to help contracting authorities identify environmentally preferable bids.[21]

Accessible procurement

The United States Section 508[22] and European Commission standard EN 301 549[23] require public procurement to promote accessibility. This means buying products and technology that has accessibility features built in to promote access for the around 1 billion people worldwide who have disabilities.[24]

Alternative competitive bidding procedures

There are several alternatives to traditional competitive bid tendering that are available in formal procurement. One approach that has gained increasing momentum in the construction industry and among developing economies is the selection in planning (SIP) process, which enables project developers and equipment purchasers to make significant changes to their requirements with relative ease. The SIP process also enables vendors and contractors to respond with greater accuracy and competitiveness as a result of the generally longer lead times they are afforded. University of Tennessee research[25] shows that Request for Solution and Request for association (also known as request for partner or request for partnership) methods are also gaining traction as viable alternatives and more collaborative methods for selecting strategic suppliers – especially for outsourcing.

Fraud

The OECD has published guidelines on how to detect and combat bid rigging.[26]

Procurement fraud can be defined as dishonestly obtaining an advantage, avoiding an obligation or causing a loss to public property or various means during procurement process by public servants, contractors or any other person involved in the procurement.[27] An example is a kickback, whereby a dishonest agent of the supplier pays a dishonest agent of the purchaser to select the supplier's bid, often at an inflated price. Other frauds in procurement include:

- Collusion among bidders to reduce competition.

- Providing bidders with advance "inside" information.

- Submission of false or inflated invoices for services and products that are not delivered or work that is never done. "Shadow vendors", shell companies that are set up and used for billing, may be used in such schemes.

- Intentional substitution of substandard materials without the customer's agreement.

- Use of "sole source" contracts without proper justification.

- Use of prequalification standards in specifications to unnecessarily exclude otherwise qualified contractors.

- Dividing requirements to qualify for small-purchase procedures to avoid scrutiny for contract review procedures of larger purchases.

Integrity Pacts are one tool to prevent fraud and other irregular practices in procurement projects. The G20 has recommended their use in their 2019 Compendium of Good Practices for Promoting Integrity and Transparency in Infrastructure Development.[28] A major European Commission pilot project entitled Integrity Pacts - Civil Control Mechanism for Safeguarding EU Funds is seeking to evaluate the effectiveness of Integrity Pacts in reducing corruption in 17 EU-funded projects in 11 Member States with a total value of over EUR 920 million.[29]

See also

- Agreement on Government Procurement

- Auction

- Bidder conferences

- Buyer leverage

- Call for bids

- Contract management

- E-procurement

- Expediting

- Global sourcing

- Group purchasing organization

- National Association of State Procurement Officials

- Presales

- Procurement outsourcing

- Performance Based Contracting

- Preferred Partnership

- Purchase order

- Purchasing

- Rate contract

- Reverse auction

- Selection in planning

- Spend analysis

- Strategic sourcing

- Tender notification

- Total cost of acquisition

- Turnkey

References

- Laffont, Jean-Jacques; Tirole, Jean (1993). A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation. MIT Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780262121743.

tirole laffont.

- Weele, Arjan J. van (2010). Purchasing and Supply Chain Management: Analysis, Strategy, Planning and Practice (5th ed.). Andover: Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1-4080-1896-5.

- Kirkman, Marshall Monroe (1887). The Handling of Railway Supplies: Their Purchase and Disposition. Chicago.

- Hysell, Helen (1922). The Science of Purchasing. New York: Appleton.

- Lewis, M.A. and Roehrich, J.K. (2009), Contracts, relationships and integration: Towards a model of the procurement of complex performance. International Journal of Procurement Management, 2(2):125–142.

- Caldwell, N.D. Roehrich, J.K. and Davies, A.C. (2009)

- "ISM - Supply Management Defined". Archived from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- "Glossary of Defense Acquisition Acronyms and Terms, 12th Edition (plus updates since publication), accessed on 22 April 2009, Defense Acquisition University". Archived from the original on 4 April 2007. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- Systems Engineering Fundamentals. Defense Acquisition University Press, 2001 Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- CIPS in partnership with Profex Publishing, Procurement and Supply Operations, 2012, revised 2016, pp. 1-2

- CIPS, Procurement Glossary - F Archived 14 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 14 March 2017

- Mason, L. (2018), Contract Administration, Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply, p. 114

- Jaggaer, How do you optimize addressable spend?, published 24 May 2016, accessed 16 January 2018

- "Ardent Partners Research - CPO 2011: Innovative Ideas for the Decade Ahead". Archived from the original on 24 September 2011.

- "Here's What Happened To This Company After Procurement Was Freed From Finance's Control". Procurement Sense. 22 February 2017. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- "Calling All CPOs: Here's How You Can Stand Up To Your CFO". Procurement Sense. 25 January 2017. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- "Public contracts - Your Europe - Business". Europa.eu. Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- "EC.Europa.eu". EC.Europa.eu. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- "EC.europa.eu". EC.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- "European Commission - PP Criteria".

- Buying Green - A Handbook on green public procurement. European Commission. 2016. p. 4.

- "Section508.gov - GSA Government-wide Section 508 Accessibility Program". www.section508.gov. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Standard - EN 301 549 - Mandate 376". mandate376.standards.eu. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "World report on disability". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Vitasek, Kate; Kling, Jeanne; Keith, Bonnie; Handley, David (2016). Unpacking Collaborative Bidding (PDF). Tennessee, USA: HASLAM COLLEGE OF BUSINESS. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- networkthoughts (6 July 2016). "Detecting Bid Rigging in Public Procurement – OECD Guidelines". Archived from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- "Combating Procurement Frauds Author Dr Irfan Ahmad".

- "G20 Compendium of Good Practices for Promoting Integrity and Transparency in Infrastructure Development" (PDF). OECD. OECD. 2019.

- "Improving how funds are invested and managed: Integrity Pacts". European Commission. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

Further reading

- N., Shaw, Felecia (1 October 2010). "The Power to Procure: A Look inside the City of Austin Procurement Program". Retrieved 26 October 2016. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Benslimane, Y.; Plaisent, M.; Bernard, P.: Investigating Search Costs and Coordination Costs in Electronic Markets: A Transaction Costs Economics Perspective, in: Electronic Markets, 15, 3, 2005, pp. 213–224.

- Hodges Silverstein, S.; Sager, T.: 2015. Legal Procurement Handbook (New York: Buying Legal Council).

- Keith, B.; Vitasek, K.; Manrodt, K.; Kling, J.: 2016. Strategic Sourcing in the New Economy: Harnessing the Potential of Sourcing Business Models for Modern Procurement (New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

External links

| Look up procurement in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Federal Procurement Data System (United States)

- Green public procurement (European Commission)

- Systems Engineering Fundamentals. Defense Acquisition University Press, 2001

- Disability:INclusive Workplaces – Accessible Technology Procurement Toolkit