Pro Tools

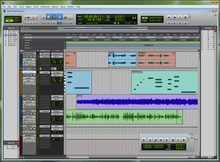

Pro Tools is a digital audio workstation developed and released by Avid Technology (formerly Digidesign)[1] for Microsoft Windows and macOS[2] used for music creation and production, sound for picture (sound design, audio post-production and mixing)[3] and, more generally, sound recording, editing and mastering processes.

| |

| Original author(s) | Evan Brooks Peter Gotcher |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Digidesign (now merged into Avid) |

| Initial release | January 20, 1989 |

| Stable release | Pro Tools 2020.5

/ May 21, 2020 |

| Written in | C, C++, Assembly |

| Operating system | macOS, Windows |

| Available in | 8 languages |

List of languages Chinese (Traditional and Simplified), English, French, German, Japanese, Korean, Spanish | |

| Type | Digital Audio Workstation |

| License | Proprietary |

| Website | www |

Pro Tools can run as standalone software or operate using a range of external analog-to-digital converters and internal PCIe cards with on-board digital signal processors (DSP), used to provide additional processing power to the host computer to process real-time effects—such as reverb, equalization and compression—[4] and to obtain lower latency audio performance.[5] Like all digital audio workstation software, Pro Tools can perform the functions of a multitrack tape recorder and a mixing console along with additional features that can only be performed in the digital domain, such as non-linear[6] and non-destructive editing—most of audio handling is done without overwriting the source files—, track compositing with multiple playlists,[7] and faster-than-realtime mixdown.

Audio, MIDI and video tracks are graphically represented in a timeline. Audio effects, virtual instruments and hardware emulators—such as microphone preamps or guitar amplifiers—can be added, adjusted and processed in real-time in a virtual mixer. 16-bit, 24-bit, and 32-bit float audio bit depths at sample rates up to 192 kHz are supported. Pro Tools supports mixed bit depths and audio formats in a session: BWF (WAV), AIFF and MXF[8] (SD2 format was dropped with Pro Tools 10).[9] It also imports and exports in the lossy formats mp3, aac, m4a and imports audio from video files (mov).[10] It has also incorporated video editing capabilities, so users can import and manipulate high definition video file formats such as XDCAM, MJPG-A, PhotoJPG, DV25, QuickTime, and more. It features time code, tempo maps, elastic audio and automation; supports mixing in surround sound, Dolby Atmos and VR sound using Ambisonics.[11]

The Pro Tools TDM mix engine, supported until 2011 with version 10, employed 24-bit fixed-point arithmetic for plug-in processing and 48-bit for mixing. Current HDX hardware systems, HD Native and native systems use 32-bit floating point resolution for plug-ins and 64-bit floating point summing;[4] the software and the audio engine were adapted to 64-bit architecture from version 11.[12]

History

| 1985 | Sound Designer |

|---|---|

| 1986 | |

| 1987 | Sound Designer Universal (1.5) |

| 1988 | |

| 1989 | Sound Tools |

| Sound Designer II | |

| 1990 | |

| 1991 | Pro Tools |

| 1992 | Sound Tools II |

| 1993 | Pro Tools II |

| 1994 | Pro Tools TDM |

| Pro Tools III | |

| 1995 | |

| 1996 | Pro Tools PCI |

| 1997 | Pro Tools 4 |

| Pro Tools | 24 | |

| 1998 | Pro Tools | 24 MIX |

| 1999 | Pro Tools 5 |

| Pro Tools LE | |

| 2000 | |

| 2001 | Pro Tools Free |

| 2002 | Pro Tools | HD |

| 2003 | Pro Tools 6 |

| 2004 | |

| 2005 | Pro Tools 7 |

| 2006 | |

| 2007 | |

| 2008 | Pro Tools 8 |

| 2009 | |

| 2010 | Pro Tools 9 |

| 2011 | Pro Tools | HDX |

| Pro Tools 10 | |

| 2012 | |

| 2013 | Pro Tools 11 |

| 2014 | |

| 2015 | Pro Tools 12 |

| Pro Tools | First | |

| 2016 | |

| 2017 | |

| 2018 | Pro Tools 2018+ |

The beginnings: Digidrums (1983–1985)

Pro Tools was developed by UC Berkeley graduates Evan Brooks, who majored in electrical engineering and computer science, and Peter Gotcher.[13]

In 1983, the two friends, sharing an interest in music and electronic and software engineering, decided to study the memory mapping of the newly released E-mu Drumulator drum machine to create EPROM sound replacement chips. The Drumulator was quite popular at that time, although it was limited to its built-in samples.[14]

They started selling the upgrade chips one year later under their new Digidrums label.[15] Five different upgrade chips were available, offering different alternate drum styles. The chips, easily switchable with the original ones, enjoyed great success between the Drumulator users, selling 60,000 units overall.[16]

Digidesign Sound Designer (1985–1989)

When Apple released its first Macintosh computer in 1984, the pair thought to develop a more functional and flexible solution which could take advantage of a graphical interface.[17] In collaboration with E-Mu, they developed a Mac-based visual sample editing system for the Emulator II keyboard, called Sound Designer, released under the Digidesign brand[18] and inspired to the interface of the Fairlight CMI.[19] This system, the first ancestor of Pro Tools, was released in 1985 at the price of US$995.[14]

Brooks and Gotcher rapidly ported Sound Designer to many other sampling keyboards, such as E-mu Emax, Akai S900, Sequential Prophet 2000, Korg DSS-1 and Ensoniq Mirage.[19] Thanks to the universal file specification subsequently developed by Brooks with version 1.5,[19] Sound Designer files could be transferred via MIDI between sampling keyboards of different manufacturers.[20] This universal file specification, along with the printed source code to a 68000 assembly language interrupt driven MIDI driver, were distributed through Macintosh MIDI interface manufacturer Assimilation, which manufactured the first MIDI interface for the Mac in 1985.

Starting from the same year, a dial-up service provided by Beaverton Digital Systems, called MacMusic, allowed Sound Designer users to download and install the entire Emulator II sound library to other less expensive samplers: sample libraries could be shared across different manufacturers platforms without copyright infringement. MacMusic contributed to Sound Designer success by leveraging both the universal file format and by developing the first online sample file download site in the world, many years before the World Wide Web use soared. The service used 2400-baud modems and 100 MB of disk with Red Ryder host on a 1 MB Macintosh Plus.[19]

With the release of Apple Macintosh II in 1987, which provided card slots, a hard disk and more capable memory, Brooks and Gotcher saw the possibility to evolve Sound Designer into a featured digital audio workstation. They discussed with E-mu the possibility of using the Emulator III as a platform for their updated software, but E-mu rejected this offer. Therefore, they decided to design both the software and the hardware autonomously. Motorola, which was working on their 56K series of digital signal processors, invited the two to participate to its development. Brooks designed a circuit board for the processor, then developed the software to make it work with Sound Designer. A beta version of the DSP was ready by December 1988.[17]

Digidesign Sound Tools and Sound Designer II software (1989–1990)

The combination of the hardware and the software was called Sound Tools. Advertised as the "first tapeless studio",[17] it was presented on January 20, 1989 at the NAMM annual convention. The system relied on a NuBus card called Sound Accelerator, equipped with one Motorola 56001 processor. The card provided 16-bit playback and recording at 44.1/48 kHz sample rates through a two-channel A/D converter (AD In), while the DSP handled signal processing, which included a ten-band graphic equalizer, a parametric equalizer, time stretching with pitch preservation, fade-in/fade-out envelopes and crossfades ("merging") between two sound files.[21][22]

Sound Tools was bundled with Sound Designer II software, which was, at this time, a simple mono or stereo audio editor running on Mac SE or Mac II; digital audio acquisition from DAT was also possible.[23] A two-channel digital interface (DAT-I/O) with AES/EBU and S/PDIF connections was made available later in 1989, while the Pro I/O interface came out in 1990 with 18-bit converters.[1]

The file format used by Sound Designer II (SDII) became eventually a standard for digital audio file exchange until the WAV file format took over a decade later. Hard drives were used to stream audio and non-destructive editing and the software was still limited by their performance, so densely edited tracks could cause glitches.[24] However, the rapidly-evolving computer technology allowed developments towards a multi-track sequencer.

Deck, Pro Tools, Sound Tools II and Pro Tools II (1990–1994)

The core engine and much of the user interface of the first iteration of Pro Tools was based on Deck. The software, published in 1990, was the first multi-track digital recorder based on a personal computer. It was developed by OSC, a small San Francisco company founded the same year, in conjunction with Digidesign and ran on Digidesign's hardware.[25] Deck could run four audio tracks with automation; MIDI sequencing was possible during playback and record, and one effect combination could be assigned to each audio track (2-band parametric EQ, 1-band EQ with delay, 1-band EQ with chorus, delay with chorus).[26]

The first Pro Tools system launched on June 5, 1991. It was based on an adapted version of Deck ("ProDeck") along with Digidesign's new editing software, "ProEdit"; Sound Designer II was still supplied for two-channel editing.[27] Pro Tools relied on Digidesign's Audiomedia card, mounting one Motorola 56001 processor[28] with a clock rate of 22.58 MHz[29] and offering two analog and two digital channels of I/O, and on the Sound Accelerator card. External synchronisation with audio and video tape machines was possible with SMPTE timecode and the Video Slave drivers.[27] The complete system was selling for US$6,000.[30]

Sound Tools II was launched in 1992 with a new DSP card, along with the Pro Master 20 interface, providing 20-bit A/D conversion,[27] and the Audiomedia II card, with one Motorola 56001 processor running at 33.86 MHz and improved digital converters.[31]

In 1993, Josh Rosen, Mats Myrberg and John Dalton, the OSC's engineers who developed Deck, split from Digidesign to focus on releasing lower-cost multi-track software that would run on computers with no additional hardware. This software was known as Session (for stereo-only audio cards) and Session 8 (for multi-channel audio interfaces) and was selling for US$399.[32][25]

Peter Gotcher felt that the software needed a major rewrite. Pro Tools II, the first software release fully developed by Digidesign, followed in the same year and addressed the weaknesses of its predecessor.[16] The editor and the mixer were merged into a single application, while a specific software, the Digidesign Audio Engine (DAE), was provided as a separate application to favor hardware support from third-party developers, enabling the use of Pro Tools hardware and plugins on other DAWs.[14] Selling more than 8,000 systems worldwide, Pro Tools II became the best selling digital audio workstation.[16]

Pro Tools II TDM: 16 tracks and real-time plug-ins (1994)

In 1994, Pro Tools 2.5 implemented Digidesign's newly developed time-division multiplexing technology, which allowed routing of multiple digital audio streams between DSP cards. With TDM, up to four NuBus cards could be linked obtaining a 16-track system, while multiple DSP-based plug-ins could be run simultaneously and in real-time.[33] The wider bandwidth required to run the larger number of tracks was achieved with a SCSI expansion card developed by Grey Matter Response, called System Accelerator.[27]

In the same year, it was announced that Digidesign would have merged into the American multimedia company Avid,[34] developer of the digital video editing platform Media Composer and one of Digidesign's major customers (25% of Sound Accelerator and Audiomedia cards produced was being bought by Avid). The operation was finalized in 1995.[33]

Pro Tools III: 48 tracks, DSP Farm cards and switch to PCI cards (1995–1997)

With a redesigned Disk I/O card, Pro Tools III was able to provide 16 tracks with a single NuBus card;[35] the system could be expanded using TDM to up to three Disk I/O cards, achieving 48 tracks.[33] To increase the processing power needed for a more extensive real-time audio processing, DSP Farm cards were introduced, each equipped with three Motorola 56001 chips running at 40 MHz;[36] multiple DSP cards could be added for additional processing power (each card could handle the playback of 16 tracks).[28] A dedicated SCSI card was still required to provide the required bandwidth to support multiple-card systems.[35]

With the launch of Pro Tools III, Digidesign launched the 888 interface, with eight channels of analog and digital I/O, and the cheaper 882 interface.[35] The Session 8 system included a control surface with eight faders.[37] A series of TDM plug-ins were bundled with the software, including dynamics processing, EQ, delay, modulation and reverb.[33]

In 1996, following Apple's decision to drop NuBus in favor of PCI bus, Digidesign added PCI support with the release of Pro Tools 3.21. The PCI version of the Disk I/O card incorporated a high-speed SCSI interface along with DSP chips,[35] while the upgraded DSP Farm PCI card included four Motorola 56002 chips running at 66 MHz.[38]

This change of architecture allowed convergence of Macintosh computers with Intel-based PCs, for which PCI had become the standard internal communication bus.[28] With the PCI version of Digidesign's Audiomedia card in 1997 (Audiomedia III),[39] Sound Tools and Pro Tools could be run on Windows platforms for the first time.[28]

24-bit audio and surround mixing: Pro Tools | 24 and Pro Tools | 24 MIX (1997–2002)

With the release of Pro Tools | 24 in 1997, a new 24-bit interface (the 888|24) and a new PCI card (the d24) were introduced. The d24 was based on Motorola 56301 processors, offering increased processing power and 24 tracks of 24-bit audio,[40] later increased to 32 tracks with a DAE software update. To keep up with the increased data throughput, a SCSI accelerator was needed. The proprietary Digidesign SCSI controller was dropped in favor of commercially available ones.[33]

64 tracks with dual d24 support were introduced with Pro Tools 4.1.1 in 1998,[41] while the updated Pro Tools | 24 MIX system provided three times more DSP power with the MIX Core DSP cards; MIXplus systems combined a MIX Core with a MIX Farm, obtaining a performance increase of 700% compared to a Pro Tools | 24 system.[33]

Pro Tools 5 saw two important software developments: extended MIDI functionality and integration in 1999 (an editable piano-roll view in the editor; MIDI automation, quantize and transpose)[33] and the introduction of surround sound mixing and multichannel plug-ins—up to the 7.1 format—with Pro Tools TDM 5.1[42] in 2001.[41]

It was at this point that the migration from traditional, tape-based analog studio technology to the Pro Tools platform took place within the industry.[17] Ricky Martin's "Livin' la Vida Loca" (1999) was the first Billboard Hot 100 number-one single to be recorded, edited, and mixed fully within the Pro Tools environment,[43] allowing a simpler and meticulous editing workflow (especially on vocals).[44]

While consolidating its presence in professional studios, Digidesign began to target the mid-range consumer market in 1999 with the introduction of the Digi001 bundle, consisting in a rack-mount audio interface with eight inputs and outputs with 24-bit, 44.1/48 kHz capability and MIDI connections. The package was distributed with Pro Tools LE, a specific version of the software without DSP support, limited to 24 mixing tracks.[14]

High-resolution audio and consolidation of digital recording and mixing: Pro Tools | HD (2002–2011)

Following the launch of Mac OS X operating system in 2001, Digidesign made a substantial redesign of Pro Tools hardware and software. Pro Tools | HD was launched in 2002, replacing the Pro Tools | 24 system and relying on a new range of DSP cards (HD Core and HD Process, replacing MIX Core and MIX Farm), new interfaces running at up to 192 kHz or 96 kHz sample rates (HD 192 and 96, replacing 888 and 882), along with a new version of the software (Pro Tools 6) with new features and a redesigned GUI, developed for OS X and Windows XP.[45] Two HD interfaces could be linked together for increased I/O through a proprietary connection. The base system was selling for US$12.000, while the full system was selling for US$20.000.[17]

Both HD Core and Process cards mounted nine Motorola 56361 chips running at 100 MHz, each providing 25% more processing power than the Motorola 56301 chips mounted on MIX cards; this translated in about twice the power for a single card. A system could combine one HD Core card with up to two HD Process cards, supporting playback for 96/48/12 tracks at 48/96/192 kHz sample rates (with a single HD Core card installed) and 128/64/24 tracks at 48/96/192 kHz sample rates (with one or two HD Process cards).[46]

When Apple changed the expansion slot architecture of the Mac G5 to PCI Express, Digidesign launched a line of PCIe DSP cards that both adopted the new card slot format and also slightly changed the combination of chips. HD Process cards were replaced with HD Accel, each mounting nine Motorola 56321 chips running at 200 MHz and each providing twice the power than a HD Process card; track count for systems mounting an HD Accel was extended to 192/96/36 tracks at 48/96/192 kHz sample rates.[47] The use of PCI Express connection reduced round-trip delay time, while DSP audio processing allowed the use of smaller hardware buffer sizes during recording, assuring stable performance with very low latency.[5]

Through the decade, Pro Tools, offering a solid and reliable alternative to analog recording and mixing, eventually became a standard in professional studios, while editing features such as Beat Detective (introduced with Pro Tools 5.1 in 2001)[42] and Elastic Audio (introduced with Pro Tools 7.4 in 2007)[48] redefined the workflow adopted in contemporary music production.[14]

Other software milestones were background tasks processing (such as fade rendering, file conversion or relinking), real-time insertion of TDM plug-ins during playback, and a browser/database environment introduced with Pro Tools 6 in 2003;[45] Automatic plug-in Delay Compensation (ADC), introduced with Pro Tools 6.4 in 2004 and only available with TDM systems with HD Accel;[49] a new implementation of RTAS with multi-threading support and improved performance, Region groups, Instrument tracks and real-time MIDI processing, introduced with Pro Tools 7 in 2006;[50] VCA and volume trim, introduced with Pro Tools 7.2 in 2006;[51] support for 10 track inserts, MIDI Editor and MIDI Score, introduced with Pro Tools 8 in 2009.[52]

Pro Tools | MIX hardware support was dropped with version 6.4.1.

Native systems: Pro Tools LE and Pro Tools M-Powered

Pro Tools LE, first introduced and distributed in 1999 with the Digi 001 interface,[53] was a specific Pro Tools version in which the signal processing entirely relied on the host CPU. The software required a Digidesign interface to run, which acted as a copy-protection mechanism for the software. Mbox was the entry-level range of the available interface; Digi 001 and Digi 002/003, which also provided a control surface, were the upper range. The Eleven Rack also run on Pro Tools LE, included in-box DSP processing via a FPGA chip, offloading guitar amp/speaker emulation and guitar effects plug-in processing to the interface, allowing them to run without taxing the host system.

Pro Tools LE shared the same interface of Pro Tools HD, but had a smaller track count (24 tracks with Pro Tools 5, extended to 32 tracks with Pro Tools 6[45] and to 48 tracks with Pro Tools 8)[54] and supported a maximum sample rate of 96 kHz[55] (depending on the interface used). Some advanced software features, such Automatic Delay Compensation, surround mixing, multi-track Beat Detective, OMF/AAF support and SMPTE Timecode were not included. Some of them, as well as support for 48 tracks/96 voices (extended to 64 tracks/128 voices with Pro Tools 8) and additional plug-ins, were made available through an expansion package, called "Music Production Toolkit".[56] The "Complete Production Toolkit", introduced with Pro Tools 8, added support for surround mixing and for 128 tracks (while still being limited to 128 voices).[54]

With the acquisition of M-Audio in 2004–2005, Digidesign released a specific variant of Pro Tools, called M-Powered, which was equivalent to Pro Tools LE and could be run with M-Audio interfaces.[57]

The Pro Tools LE/M-Powered line was discontinued with the release of Pro Tools 9.

Advanced Instrument Research (AIR): built-in virtual instruments and plug-ins

In response to Apple's decision to include Emagic's complete line of virtual instruments in Logic Pro in 2004, and following Avid's acquisition of German virtual instruments developer Wizoo in 2005, Pro Tools 8 was supplied with its first built-in virtual instruments library, the AIR Creative Collection, as well as with some new plug-ins, to make it more appealing for music production.[54] An expansion was also available, called AIR Complete Collection.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pro Tools 9: hardware-independent native systems (2010–present)

Pro Tools 9, released on November 4, 2010, was the first version not requiring proprietary hardware, allowing use of the software with any interface. It could operate using the internal sound card of a PC via the ASIO driver and a Mac using Core Audio. Core Audio also allowed, for the first time, the use of aggregate devices, allowing the use of more than one interface at the same time. This could also be achieved on a PC by using any ASIO free anternatives. Some of the most advanced features of Pro Tools | HD software, such as automatic plug-in delay compensation, OMF/AAF file import, Timecode ruler and multitrack Beat Detective were included into the standard version of Pro Tools 9.[58]

When operating on a machine containing one or more HD Core, Accel or Native cards, the software ran as Pro Tools HD, with the complete HD feature set. In all other cases it ran as Pro Tools 9, with a smaller track count and a number of advanced features turned off.

Pro Tools | HDX (2011–present)

A new series of DSP PCIe cards, named HDX, was introduced in October 2011 along with Pro Tools 10. The new DSP processors, manufactured by Texas Instruments, allowed an increased computational precision (32-bit floating point resolution for plug-ins, instead of 24-bit fixed-point of TDM systems, and 64-bit floating point summing versus the previous 48-bit fixed),[4] thus improving dynamic range performance. Track playback and signal processing operations were managed independently by the processors; they also provided lower monitoring latency and more computational power.

The hardware line included HDX, relying on dedicated DSP and obtaining considerably lower latency for all DSP-reliant operations, and HD Native, relying on the host system's CPU for all audio processing. In order to maintain performance consistency, HDX products were specified with a fixed maximum number of voices (each voice representing a monophonic channel). Each HDX card enabled 256 simultaneous voices at 44.1/48 kHz; voice count halved when the sample rate doubled (128 voices at 88.2/96 kHz, 64 voices at 176.4/192 kHz). Up to three HDX cards could be installed on a single system for a maximum of 768/384/192 total voices and for increased processing power. On Native systems, voice count was limited to 96/48/24 voices with the standard version of Pro Tools, and to 256/128/64 voices with Pro Tools HD software.[4]

With Pro Tools 10, a new plug-in format was deployed for both Native and HDX systems, called AAX (acronym for Avid Audio eXtension).[59] AAX Native replaced RTAS plug-ins and AAX DSP, a specific format running on HDX systems, replaced TDM plug-ins. AAX was developed to provide the future implementation of 64-bit plugins, although 32-bit versions of AAX were still used in Pro Tools 10. TDM support was dropped with HDX,[60] while Pro Tools 10 would be the final release for Pro Tools | HD Process and Accel systems.

Notable software features introduced with Pro Tools 10 were editable clip-based gain automation (Clip gain), the ability to load the session's audio data into RAM to improve transport responsiveness (Disk caching), quadrupled Automatic Delay Compensation length, audio fades processed in real-time, timeline length extended to 24 hours, support for 32-bit float audio and mixed audio formats within the session, and the addition of Avid Channel Strip plugin (based on Euphonix System 5 console's channel strip, following Avid's acquisition of Euphonix in 2010).[61][42]

Switch to 64-bit architecture: Pro Tools 11 (2013–present)

Features

Workflow in Pro Tools is organized into two main windows: the timeline is shown in the Edit window, while the mixer is shown in the Mix window. MIDI and Score Editor windows provide a dedicated environment to edit MIDI.[63] Different window layouts, along with shown and hidden tracks and their width settings, can be stored and recalled from the Window configuration list.[64]

Timeline

The timeline provides a graphical representation of all types of tracks: the audio envelope or waveform (when zoomed in) for audio tracks, a piano roll showing MIDI notes and controller values for MIDI and Instrument tracks, a sequence of frame thumbnails for video tracks, audio levels for auxiliary, master and VCA master tracks.[65] Alternate audio and MIDI content can be recorded, shown and edited in multiple layers for each track (called playlists), which can be used for track compositing.[66] All the mixer parameters (such as track and sends volume, pan and mute status) and plug-in parameters can be changed over time through automation.[67] Any automation type can be shown and edited in multiple lanes for each track.[68] Track-based volume automation can be converted to clip-based automation and vice versa;[69] automation of any type can also be copied and pasted to any other automation type.[70]

Tempo and meter changes can be programmed on the timeline; both MIDI and audio clips can move or time-stretch to follow tempo changes ("tick-based" tracks) or maintain their absolute position ("sample-based" tracks). Elastic Audio must be enabled in order to allow time stretching of audio clips.[71]

Editing

Audio and MIDI clips can be moved, cut and duplicated non-destructively on the timeline (edits change the clip organization on the timeline, but source files are not overwritten).[72] Time stretching (TCE), pitch shifting, equalization and dynamics processing can be applied to audio clips non-destructively and in real-time with Elastic Audio[73] and Clip Effects;[74] gain can be adjusted statically or dynamically on individual clips with Clip Gain;[75] fade and crossfades can be applied, adjusted and are processed in real time. All other type of audio processing can be rendered on the timeline with the AudioSuite (non-real-time) version of AAX plug-ins.[76]

MIDI notes, velocities and controllers can be edited directly on the timeline, each MIDI track showing an individual piano roll, or in a specific window, where several MIDI and Instrument tracks can be shown together in a single piano roll with color-coding. Multiple MIDI controllers for each track can be viewed and edited on different lanes.[77] MIDI tracks can also be shown in musical notation within a score editor.[78] MIDI data such as note quantization, duration, transposition, delay and velocity can also be altered non-destructively and in real-time on a track-per-track basis.[79]

Video files can be imported to one or more video tracks and organized in multiple playlists. Multiple video files can be edited together and played back in real-time. Video processing is GPU-accelerated and managed by the Avid Video Engine (AVE). Video output from one video track at once is provided in a separate window or can be viewed full-screen.[80]

Mixing

The virtual mixer shows controls and components of all tracks, including inserts, sends, input and output assignments, automation read/write controls, panning, solo/mute buttons, arm record buttons, the volume fader, the level meter and the track name. It also can show additional controls for the inserted virtual instrument, mic preamp gain, HEAT settings, and the EQ curve for each track.[81] Each track inputs and outputs can have different channel depths: mono, stereo, multichannel (LCR, LCRS, Quad, 5.0/5.1, 6.0/6.1, 7.0/7.1); Dolby Atmos and Ambisonics formats are also available for mixing.[82]

Audio can be routed to and from different outputs and inputs, both physical and internal. Internal routing is achieved using busses and auxiliary tracks; each track can have multiple output assignments.[83] Virtual instruments are loaded on Instrument tracks—a specific type of track which receives MIDI data in input and returns audio in output.[84]

Plug-ins are processed in real-time with dedicated DSP chips (AAX DSP format) or using the host computer's CPU (AAX Native format).[85]

Track rendering

Audio, auxiliary and Instrument tracks (or MIDI tracks routed to a virtual instrument plug-in) can be committed to new tracks containing their rendered output. Virtual instruments can be committed to audio to prepare an arrangement project for mixing; track commit is also used to free up system resources during mixing, or when the session is shared with systems not having some plug-ins installed. Multiple tracks can be rendered at a time; it is also possible to render a specific timeline selection and define which range of inserts to render.[86]

Similarly, tracks can be frozen with their output rendered at the end of the plug-in chain or at a specific insert of their chain. Editing is suspended on frozen tracks, but they can be subsequently unfrozen if further adjustments are needed. For example, virtual instruments can be frozen to free up system memory and improve performance, while keeping the possibility to unfreeze them to make changes to the arrangement.[87]

Mixdown

The main mix of the session—or any internal mix bus or output path—can be bounced to disk in real-time (if hardware inserts from analog hardware are used, or if any audio or MIDI source is monitored live into the session) or offline (faster-than-realtime). The selected source can be mixed to mono, stereo or any other multichannel format. Multichannel mixdowns can be written as an interleaved audio file or in multiple mono files. Multiple sources can also mixed down simultaneously—for example, to deliver audio stems.[88]

Audio and video can be bounced together to a QuickTime movie file.[89]

Session data exchange

Session data can be partially or entirely exchanged with other DAWs or video editing software that support AAF, OMF, or MXF. AAF and OMF sequences embed audio and video files with their metadata; when opened by the destination application, session structure is rebuilt with the original clip placement, edits and basic track and clip automation.[90]

Track contents and any of its properties can be selectively exchanged between Pro Tools sessions with Import Session Data (for example, importing audio clips from an external session to a designated track while keeping track settings, or importing track inserts while keeping audio clips).[91] Similarly, the same track data for any track set—a given processing chain, a collection of clips or a group of tracks with their assignments—can be stored and recalled as Track Presets.[92]

Cloud collaboration

Pro Tools projects can be synchronized to the Avid Cloud and shared with other users on a track-by-track basis. Different users can work on the project simultaneously and upload new tracks or any changes to existing tracks (such as audio and MIDI clips, automation, inserted plug-ins, and mixer status) or changes to the project structure (such as tempo, meter or key).[93]

Field recorder workflows

Pro Tools reads embedded metadata in media files to manage multichannel recordings made by field recorders in production sound. All stored metadata (such as scene and take numbers, tape or sound roll name, or production comments) can be accessed in the Workspace browser.[94]

Analogous audio clips are identified by overlapping longitudinal timecode (LTC) and by one or more user-defined criteria (such as matching file length, file name, or scene and take numbers). An audio segment can be replaced from matching channels (for example, to replace audio from a boom microphone with the audio from a lavalier microphone) while maintaining edits and fades in the timeline, or any matching channels can be added to new tracks.[95]

Multi-system linking and device synchronization

Up to twelve Pro Tools Ultimate systems with dedicated hardware can be linked together over an Ethernet network—for example, in multi-user mixing environments where different mix components (such as dialog, ADR, effects, and music) reside on different systems, or if a larger track count or processing power is needed. Transport, solo and mute are controlled by a single system and with a single control surface.[96] One system can also be designated for video playback to optimize performance.[97] Pro Tools can synchronized to external devices using SMPTE/EBU timecode or MIDI timecode.[98]

Editions

Pro Tools software is available in a standard edition (informally called "Vanilla")[99] providing all the key features for audio mixing and post-production, a complete edition (officially called "Ultimate" and known as "HD" between 2002 and 2018), which unlocks functionality for advanced workflows and a higher track count, and a starter edition, called "First", providing the essential features.

| Pro Tools | First | Pro Tools | Pro Tools | Ultimate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| License type | Free | Paid (Perpetual/Subsciption) | |

| Price of perpetual licenses[103] | – | US$599 | US$2599 |

| Maximum voices, tracks and hardware inputs | |||

| Voices (48 / 96 / 192 kHz) |

16 / 16 / – (mono or stereo tracks) |

128 / 64 / 32 (mono or stereo tracks) |

384 / 192 / 96 (Native) |

| 786 / 384 / 192 (HDX) | |||

| I/O channels | 4 | 32 | 192 |

| MIDI tracks | 16 | 1024 | |

| Instrument tracks | 16 | 512 | |

| Auxiliary tracks | 16 | 128 | 512 |

| Video tracks | – | 1 | 64 |

| Bit depth, Sample rate | 32-bit float, 96 kHz | 32-bit float, 192 kHz | |

| Production tools | |||

| Editing tools | Basic | Standard | Advanced |

| MIDI editor, Elastic Audio, Elastic Pitch, Track presets |

Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Score editor, Beat Detective, Input monitoring, Clip gain |

No | Yes | Yes |

| Clip effects | No | Read-only | Full |

| Batch Track/Clip rename | No | Yes | Yes |

| Video editing tools | No | No | Yes |

| Mixing tools | |||

| Mixing output | Stereo | Stereo | Up to 7.1.2 surround |

| Automation | Standard | Standard | Advanced |

| Plug-in delay compensation, Offline bounce, Track freeze |

Yes | Yes | Yes |

| VCA, AFL/PFL solo path, Timecode, Advanced metering |

No | Yes | Yes |

| Dolby Atmos, Ambisonics VR and surround mixing |

No | No | Yes |

| HEAT | No | No | Yes (Paid) |

| Program features | |||

| Cloud collaboration | Yes (includes 1 GB of free storage space) | ||

| AAF / OMF / MXF file support | No | Yes | Yes |

| Session data importing | No | Yes | Yes |

| Disk cache | No | Yes | Yes |

| Satellite link (sync up to 12 systems) |

No | No | Yes |

Control surfaces

In mid 1990s, Digidesign started working on a studio device which could replace classic analog consoles and provide integration with Pro Tools. ProControl (1998) was the first Digidesign control surface, providing motorised, touch-sensitive faders, an analog control room communication section and connecting to the host computer via Ethernet. ProControl could be later expanded by adding up to five fader packs, each providing eight additional fader strips and controls.[33]

Control 24 (2001) added 5.1 monitoring support and included 16 class A preamps designed by Focusrite. Icon D-Control (2004) incorporated an HD Accel system and was developed for larger TV and film productions in mind. Command|8 (2004) and D-Command (2005) were the smaller counterparts of Control 24 and D-Control, connected with the host computer via USB; Venue (2005) was a similar system specifically designed for live sound applications.[42]

C|24 (2007) was a revision of Control 24 with improved preamps, while Icon D-Control ES (2008) and Icon D-Command ES (2009) were redesigns of Icon D-Control and D-Command.[42]

In 2010 Avid acquired Euphonix, manufacturer of the Artist Series and System 5 control surfaces. They were integrated with Pro Tools along with the EuCon protocols. The Avid S6 (2013) and Avid S3 (2014) control surfaces followed merging the Icon and System 5 series. Pro Tools Dock (2015) was a iPad-based control surface running Pro Tools Control software.[104]

Timeline of Pro Tools hardware and software

| Year | Software | Hardware | Release information |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1985 | Sound Designer | Macintosh-based visual sample editing software developed for the E-Mu Emulator II sampler dedicated ports of the original software were subsequently released for Emax, Prophet 2000, S900, DSS-1 and Mirage samplers[19] | |

| 1987 | Sound Designer 1.5 | Sound Accelerator | universal version with enhanced editing features through the Mac's hardware (mix, crossfade, gain and equalization) and supporting a variety of samplers compatible with Sound Accelerator NuBus card, equipped with one Motorola 56001 chip, providing dedicated DSP hardware[19] |

| 1989 | Sound Tools | stereo hard-disk recording and editing system with 16-bit audio, 44.1 kHz or 48 kHz sample rate adopting the SDII proprietary audio format[105] relies on a Sound Accelerator NuBus card connected to an external 2-channel AD converter and Sound Designer II software running on Macintosh SE and Mac II[1] | |

| Sound Designer II | Sound Accelerator Audiomedia I | ||

| 1991 | Pro Tools | Mac-based 4-track digital production system handled by ProEdit (editing software) and ProDeck (mixing software) MIDI sequencing and automation[105][27] | |

| ProEdit ProDeck |

|||

| 1992 | Pro Tools 1.1 | 4–16 voices support in mixing using up to 4 cards/interfaces[105] | |

| Sound Tools II | support for Pro Master 20 interface with 20-bit A/D conversion[27] | ||

| 1993 | Pro Tools II | editing and mixing software merged in a single application called Pro Tools with the component DAE (Digidesign Audio Engine) 4 voices support[27][41] | |

| Audiomedia II | |||

| 1994 | Pro Tools II TDM (2.5) | TDM technology enables real-time effects to run as software plug-ins; up to 4 NuBus cards can be linked together[27][41] | |

| Pro Tools III | 16–48 voices on NuBus-based Mac systems (up to 3 cards linkable)[35] DSP Farm NuBus card equipped with 3 Motorola 56001 chips (40 MHz clock speed) for additional processing power[36] software editing functionality improved | ||

| DSP Farm | |||

| 1996 | Pro Tools III PCI | 16–48 voices for PCI-based Mac systems (up to 3 cards linkable) 88x series interfaces with 8 channels I/O, 16-bit AD/DA converters, AES/EBU I/O[35][41] DSP Farm PCI card equipped with 4 Motorola 56002 chips (66 MHz clock speed)[38] | |

| Pro Tools 3.21 | 888 I/O, 882 I/O DSP Farm | ||

| 1997 | Pro Tools 4 | Pro Tools Project Card | WAV and QuickTime file support; Sound Designer file editing features integrated in AudioSuite tool set runs on Pro Tools III NuBus/PCI systems or without TDM hardware with limitations (Project or PowerMix versions) destructive editing integrated, fade improvements, Strip Silence, continuous playback during editing, independently-resizable tracks, up to 26 track groups, automation extended to all mixer and plug-in parameters, new automation modes Loop Record, Half-Speed Record, Destructive Record, QuickPunch (punch-in and out recording during playback) Edit window configurations can be saved and recalled with Memory Locations[41][106] |

| Pro Tools | 24 | 24–48 or 32–64 channels of 24-bit audio I/O support via the d24 PCI card[40] 88x interface line upgraded with 24-bit AD converters, 20-bit DA converters (888|24), 20-bit AD/DA converters (882|20)[107] | ||

| Pro Tools 4.1 | d24 888|24, 882|20 | ||

| 1998 | Pro Tools | 24 MIX | 16–48 I/O channels, 64 voices MIX, MIXplus and MIX3 system configurations with one MIX Card and up to two MIX Farm PCI cards equipped with 6 Motorola Onyx chips[107] | |

| Pro Tools 4.3 | MIX Card MIX Farm | ||

| ADAT Bridge I/O | 20-bit digital interface with 16 ADAT optical input channels[108] | ||

| ProControl | first dedicated control surface for Pro Tools using Ethernet connection with microphone and line inputs[109] | ||

| 1999 | Pro Tools 5 | integrated MIDI and audio editing/mixing,[109] MIDI piano-roll display, graphic MIDI velocity editing, MIDI quantize single-stroke key commands for editing, Region Replace, floating video window[53] | |

| 2000 | Pro Tools LE | Digi 001 (LE) | mid-level recording system with 24 tracks, 8 analog I/O channels, 2 microphone preamps, 24-bit AD/DA, digital I/O and MIDI rack-mountable interface connected with a PCI card running a new feature-limited software line ("Light Edition") with RTAS host-based processing (without DSP)[110][53] |

| Control|24 | touch-sensitive control surface equipped with 24 Focusrite preamps[110] | ||

| 2001 | Pro Tools Free | free version with essential features, based on version 5, runs natively on OS 9, OS 8.6, Windows 98, Windows ME 8 audio tracks, 48 MIDI tracks, RTAS support | |

| Pro Tools 5.1 | surround mixing, Beat Detective (TDM)[41] | ||

| 2002 | Pro Tools | HD | HD software and hardware line adds support for 192 kHz and 96 kHz sample rates, runs with 192 I/O and 96 I/O interfaces providing 32–96 I/O channels HD1–HD3 systems are based on one HD Core adding up to two HD Process PCI-based cards equipped with 9 Motorola 56361 DSP chips (100 MHz clock speed) 96/48/12 tracks at 48/96/192 kHz sample rates with HD1 systems 128/64/24 tracks at 48/96/192 kHz sample rates with HD2/HD3 systems[110][41][46] | |

| Pro Tools 5.3.1 | 192 I/O, 96 I/O SYNC, MIDI, PRE | ||

| HD Core HD Process | |||

| Mbox (LE) | low-cost USB-powered audio interface with 2 analog inputs, 1 mic preamp, S/PDIF digital I/O, bundled with Pro Tools LE software[110] | ||

| Digi 002 (LE) | mid-level FireWire audio interface with 8 analog inputs, 24-bit/96 kHz converters, touch-sensitive control surface, running Pro Tools LE 5.3.2 on Windows XP and Mac OS 9[110][55] | ||

| 2003 | Pro Tools 6 | support for Mac OS X platform (OS 9 dropped), GUI redesign, real-time plug-in insertion for TDM systems Relative Grid mode, support for timeline vertical selection Digibase (workspace browser and database environment) for media/project management 256 MIDI tracks, Groove Template, additional MIDI commands, Import Session Data replaces Import Tracks new DigiRack plug-ins, more powerful LE version[45] | |

| Pro Tools 6.1 | support for Windows XP and ReWire, support for AAF[41] | ||

| Digi 002 Rack (LE) | mid-level FireWire audio interface with up to 18 I/O channels, 4 mic preamps, 24-bit/96 kHz AD/DA, support for 32 tracks with Pro Tools LE software[111] | ||

| HD Accel (HD) | DSP cards expansion equipped with 9 Motorola 56321 chips (200 MHz clock speed) twice the power as the HD Process cards, extends track count to 192/96/36 tracks at 48/96/192 kHz sample rates (combined with one HD core card)[111][47] | ||

| 2004 | Pro Tools 6.4 | +12 dB fader range support for Command 8 control surface, Automatic Delay Compensation, TrackPunch, input monitoring on single tracks (HD)[49] | |

| Pro Tools 6.9 | 160 auxiliary tracks, 128 busses, Surround Panner support, selectable PFL/AFL solo paths (HD) selectable solo mode (Latch or X-OR), new keyboard shortcuts, I/O setup improvements[112] | ||

| ICON D-Control ICON D-Command |

modular control surface line with 16–32 (D-Control) or 8–24 (D-Command) touch-sensitive faders and HD3 Accel DSP system[113] | ||

| 2005 | Pro Tools M-Powered | standalone feature-limited product line bundled with M-Audio interfaces, same as Pro Tools LE[57] | |

| Pro Tools 7 | HD Accel PCIe (HD) | multi-threading RTAS engine improves performance on multi-core systems, support for 10 sends per track, Instrument tracks, Region Groups, region looping, real-time MIDI processing, new session format with Mac/PC interoperability; 160 I/O at 96 kHz (HD)[50] | |

| VENUE | new line of modular digital mixing consoles with DSP and integrated playback and recording with Pro Tools[114] | ||

| Mbox 2 (LE) | second generation of the Mbox USB audio interface[115] | ||

| 2006 | Pro Tools 7.11 | support for Intel-based Macs, Hybrid and Xpand! software sampler plug-ins added | |

| Pro Tools 7.2 | digital VCA groups, enhanced automation, enhanced track grouping system, extended support for contextual menus, Dubber and Field Recorder enhancements; support for multiple Video tracks (HD)[51] | ||

| Pro Tools 7.3 | Dynamic Transport, Windows Configurations, Key Signature timeline ruler, MIDI selection enhancements, fade editing enhancements, continuously-resizable tracks, mixer configurations changes possible without stopping playback, mouse scroll wheel and right-click enhancements, Memory Location and Digibase enhancements, Signal Tools and Time Shift plug-ins added, MIDI data can be exchanged with Sibelius scoring software[116] | ||

| Mbox 2 Pro (LE) Mbox 2 Mini (LE) |

new formats/variants of Mbox 2 | ||

| 2007 | Pro Tools 7.4 | Elastic Audio, Digibase browser enhancements[48] | |

| Digi 003 (LE) Digi 003 Rack (LE) |

|||

| Mbox 2 Micro (LE) | portable USB interface with mini-jack stereo output and bundled with Pro Tools LE; support limited to 44.1/48 kHz sample rates[117] | ||

| 2008 | Pro Tools 8 | revamped user interface, support for 10 inserts per track, Playlist view and enhanced track compositing tools, support for multiple automation lanes view, Elastic Pitch, MIDI Editor, Score Editor, AIR Creative Collection; Automatic Delay Compensation on sends (HD)[52] | |

| Digi 003 Rack + (LE) | |||

| 2009 | Eleven Rack | guitar effects processor with Pro Tools LE DSP | |

| Mbox (LE) Mbox Pro (LE) Mbox Mini (LE) |

third generation, first full release by Avid | ||

| 2010 | Pro Tools 8.1 | HEAT software add-on (HD) | |

| Pro Tools 9 | "standard" version replaces LE and M-Powered lines, gets most of the HD-only software features and can be run on native systems with ASIO or Core Audio driver protocols full HD features can be purchased with Complete Production Toolkit 2 added 7.0/7.1 surround support (HD)[58][118] | ||

| HD I/O, HD OMNI, HD MADI, SYNC HD | HD Series Interfaces introduced, replaces the previous "blue" HD series[119] | ||

| HD Native | PCI card or Thunderbolt interface, enables to run HD software on up to two HD (or HD-compatible) interfaces with low-latency performance and without DSP[120] | ||

| 2011 | Pro Tools | HDX | 96 voices, 512 Instrument tracks, 128 aux inputs, 1 video track, 128/64/32 tracks at 48/96/192 kHz sample rates (standard version) 256–768 voices, 512 Instrument tracks, 512 aux inputs, 64 video tracks, 256–768 tracks at 48 kHz sample rates, 64–192 I/O channels (HDX systems with 1–3 HDX cards) HDX replaces HD Core systems and HD1–HD3 configurations; each PCI card is equipped with 18 Texas Instruments DSP chips (350 MHz clock speed), can run AAX DSP plug-ins AAX (Avid Audio eXtension) plug-in format introduced with 64-bit ready SDK (32-bit still used); AAX DSP plug-ins replaces TDM plug-ins in HD systems, RTAS still supported improved recording playback performance (disk cache, NAS support, disk scheduler improvements) Clip Gain, disk cache, real-time fades, 4x maximum Automatic Delay Compensation, 24-hour timeline, support for mixed file formats and 32-bit float resolution, interface improvements, Avid Channel Strip plug-in[4][118] | |

| Pro Tools 10 | HDX | ||

| 2013 | Pro Tools 11 | application upgraded with 64-bit architecture. 32-bit RTAS and TDM plug-in support dropped in favor of 64-bit AAX format; support discontinuation for HD Accel systems Offline bouncing, Dynamic Plug-In processing optimizes session performance; up to 16 sources can be bounced simultaneously, advanced metering options (HD)[12] | |

| 2014 | Duet Quartet |

two/four channel USB interface and monitor controller with 192 kHz AD/DA conversion developed by Apogee | |

| 2015 | Pro Tools | First | free software line with essential features, cloud-based sessions up to 96 kHz sample rate, 16 tracks per type (audio, MIDI, Instrument and auxiliary), 4 I/O channels, MIDI editor, Elastic Time, Elastic Pitch, Workspace, AAX Native and AudioSuite[62][118] | |

| Pro Tools 12 | available as monthly or yearly subscription; metadata tagging, updated I/O setup[118] | ||

| Pro Tools 12.1 | increased track count, AFL/PFL solo modes, copy to sends, native HEAT support (HD)[118] | ||

| Pro Tools 12.2 | VCAs, Disk Caching, advanced metering options unlocked to standard version[118] | ||

| Pro Tools 12.3 | Commit, fade presets, batch fades, clip graphic overlay[118] | ||

| Pro Tools 12.4 | Track Freeze, fade workflows[118] | ||

| 2016 | Pro Tools 12.5 | Cloud Collaboration, updated Avid Video Engine, send to playback (Interplay)[118] | |

| Pro Tools 12.6 | Clip Effects, Layered Editing, playlist improvements[118] | ||

| Pro Tools 12.7 | project revision history, workspace improvements software support for Pro Tools | MTRX[118] | ||

| 2017 | Pro Tools 12.8 | Pro Tools | MTRX | Dolby Atmos integration and NEXIS optimization (HD); workspace and project enhancements; Cloud Collaboration (First)[118] |

| Pro Tools 12.8.2 | Ambisonics VR Track support, Dolby Atmos enhancements, improved MIDI editing and recording features, Batch renaming features[118] | ||

| 2018 | Pro Tools 2018.1 | iLok Cloud support, Track Presets, assignable target playlist, retrospective MIDI record, MIDI editing enhancements, EQ Curve can be shown in the Mix window, improved Import Session Data[118] First version to adopt new version numbering scheme with a release year and month being a version number. | |

| Pro Tools 2018.4 | "Pro Tools | HD" software line rebranded as "Pro Tools | Ultimate" bug fixes and stability improvements[118] | ||

| Pro Tools 2018.7 | real-time search in track inserts and I/O (busses and sends), multiple selection within I/O and interface menus, playlist navigation shortcuts added, Relative Grid mode extended to cut, copy, paste, and merge, retrospective MIDI record enhancements, Low Latency Monitoring enhancements; bug fixes[121] | ||

| Pro Tools 2018.12 | bug fixes and stability improvements[122] | ||

| 2019 | Pro Tools 2019.5 | 384–96 voices on native systems (Ultimate), 1024 MIDI tracks performance improvements (HDX / HD Native) continuous playback on most timeline and track interactions, key commands added; bug fixes[123] | |

| Pro Tools 2019.6 | bug fixes[124] | ||

| Pro Tools 2019.10 | support for up to 130 outputs with Dolby Audio Bridge, multi-stem bounce in a single file (Ultimate) updated Avid Video Engine with 4K/60 fps support and H.264 playback performance improvements, steep break-point smoothing option added, AAF importing improvements, SMPTE ID support for wave files, key commands added; bug fixes[125] | ||

| Pro Tools 2019.12 | bug fixes and stability improvements[126] | ||

| 2020 | Pro Tools 2020.3 | Pro Tools | MTRX Studio | Folder Tracks, Resources section added in System Usage, H.264 performance improvements extended; bug fixes and stability improvements support for Pro Tools | MTRX Studio[127] |

| Pro Tools 2020.5 | optimizations for session storage on cloud services; bug fixes and stability improvements[128] | ||

See also

- Comparison of multitrack recording software

- List of music software

References

Footnotes

- Collins 2002, p. 9.

- "Pro Tools Operating System Compatibility Chart". avid.force.com. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- "Pro Tools | Ultimate - Audio Editing Software - Features". Avid. July 25, 2019. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- Wherry, Mark (April 2012). "Avid HDX". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- Thornton, Mike (February 2015). "Working Late". Sound on Sound. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- Avid 2019, p. 7, 2. Pro Tools Concepts.

- Thornton, Mike (April 2009). "Track Comping". Sound on Sound. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- Avid 2019, p. 158, 11. Session and Projects.

- "Sound Designer II audio file support with Pro Tools 10.3.6 and higher". avid.force.com. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- "What type of files can Pro Tools import? | Sweetwater". SweetCare. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- Sherbourne, Simon (October 18, 2017). "Ambisonics and VR/360 Audio in Pro Tools | HD". Avid Blogs. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- Wherry, Mark (September 2013). "Avid Pro Tools 11". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- Payne, John (October 4, 2008). "The Software Chronicles". EQ Mag. Archived from the original on October 4, 2008. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- "A brief history of Pro Tools". MusicRadar. May 30, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- Battino & Richards 2005, p. 38–39.

- "Digidesign Past & Present". Sound on Sound. March 1995. Archived from the original on June 6, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- Milner 2009, p. 245.

- Devereux, Brian (May 1986). "Sound Designer 2000 Software". Electronic & Music Maker: 24 – via http://www.muzines.co.uk.

- "Sample Editors: Sound Designer". Emulator Archive. February 25, 2009. Archived from the original on February 25, 2009. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- Mellor, David (October 1988). "Sound Designer Universal". Sound on Sound. 36: 24–26 – via http://www.muzines.co.uk/.

- Manning 2013, p. 387.

- Lehrman, Paul D. (August 1989). "Digidesign Sound Tools". Sound on Sound. 46: 60–63 – via http://www.muzines.co.uk/.

- Mellor, David (November 1991). "Hands on: Sound Tools". Sound on Sound. 73: 70–74 – via http://www.muzines.co.uk/.

- Brooks, Evan (January 20, 2007). "NAMM Library: Oral History". NAMM.org. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- Goldberg, Michael (December 1994). "Consume the Minimum, Produce the Maximum". Wired. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- Lehrman, Paul D. (November 1990). "Digidesign Deck". Sound on Sound. 61: 60–64 – via http://www.muzines.co.uk.

- Collins 2002, p. 10.

- Manning 2013, p. 389.

- "Audiomedia I in/out specification - Avid Pro Audio Community". duc.avid.com. Retrieved January 12, 2020.

- Millner 2009, p. 216.

- "Audiomedia II". archive.digidesign.com. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- Waugh, Ian (November 1993). "Digidesign Session 8". Music Technology. 85: 56–58 – via www.muzines.co.uk.

- Thornton, Mike (November 3, 2018). "The History of Pro Tools - 1994 to 2000". Production Expert. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- The Associated Press (October 26, 1994). "Company News; Avid Technology Plans to Acquire Digidesign". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- Collins 2002, p. 11.

- "DSP Farm - NuBus". archive.digidesign.com. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- Boss, Todd D. (March 1994). "Test Drive: The Digidesign Session 8 - Radio And Production". rapmag.com. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- "DSP Farm, PCI". archive.digidesign.com. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- "Audiomedia III". archive.digidesign.com. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- Collins, Mike (1998). "Digidesign Pro Tools". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- "Release dates and versions for Pro Tools HD/TDM (prior to v9)". avid.force.com. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- Thornton, Mike (November 3, 2018). "The History of Pro Tools - 2000 to 2007 | Pro Tools". Production Expert. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- Daley, Dan (November 1999). "Recordin' "La Vida Loca": the making of a hard disk hit". Mix Magazine. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011.

- Milner 2009, p. 216.

- Price, Simon (May 2003). "Digidesign Pro Tools 6". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Denten, Michael; Hawkins, Erik (September 2002). "Digidesign Pro Tools|HD". Mix Magazine. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- "Digidesign HD Accel PCI Card". Mix Magazine. September 15, 2003. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- Thornton, Mike (January 2008). "Digidesign Pro Tools 7.4". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Price, Simon (July 2004). "Pro Tools 6.4 Update". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Wherry, Mark (January 2006). "Digidesign Pro Tools 7". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Price, Simon (September 2006). "Digidesign Pro Tools 7.2". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Wherry, Mark (January 2009). "Digidesign Pro Tools 8". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- "Digidesign Digi 001". Sound on Sound. December 1999. Archived from the original on June 9, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- Mark, Wherry (February 2009). "Digidesign Pro Tools 8: Part 2". Sound on Sound. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- Poyser, Debbie; Johnson, Derek (December 2002). "Digidesign Digi 002". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- Inglis, Sam (June 2006). "Digidesign Hybrid & Music Production Toolkit". Sound on Sound. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- Inglis, Sam (June 2005). "Pro Tools M-Powered". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- Inglis, Sam (January 2011). "Avid Pro Tools 9". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Hughes, Russ (September 22, 2014). "A-Z of Pro Tools - A is for AAX". Production Expert. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- "Pro Tools DigiRack Plug-Ins Guide: Version 5.0.1 for Macintosh and Windows" (PDF). Digidesign, Inc. 2000. p. 18. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- Wherry, Mark (March 2012). "Avid Pro Tools 10". Sound on Sound. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- Wherry, Mark (January 2016). "Avid Pro Tools 12.3". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- Avid 2019, p. 187–190, 12. Pro Tools Main Windows.

- Avid 2019, p. 205–213, 12. Pro Tools Main Windows.

- Avid 2019, p. 190, 12. Pro Tools Main Windows.

- Avid 2019, p. 691, 32. Playlists.

- Avid 2019, p. 1125–1126, 50. Automation.

- Avid 2019, p. 1135–1138, 50. Automation.

- Avid 2019, p. 947, 43. Clip Gain and Clip Effects.

- Avid 2019, p. 1160, 50. Automation.

- Avid 2019, p. 16, 2. Pro Tools Concepts.

- Avid 2019, p. 653–664, 30. Editing Clips and Selections.

- Avid 2019, p. 695, 44. Elastic Audio.

- Avid 2019, p. 949–950, 43. Clip Gain and Clip Effects.

- Avid 2019, p. 941, 43. Clip Gain and Clip Effects.

- Avid 2019, p. 929, 42. AudioSuite Processing.

- Avid 2019, p. 787, 35. MIDI Editors.

- Avid 2019, p. 805, 36. Score Editor.

- Avid 2019, p. 780, 34. MIDI Editing.

- Avid 2019, p. 1355–1357, 60. Working with Video in Pro Tools.

- Avid 2019, p. 188, 12. Pro Tools Main Windows.

- Avid 2019, p. 1201–1203, 52. Pro Tools Setup for Surround.

- Avid 2019, p. 1057, 48. Basic Mixing.

- Avid 2019, p. 1046, 48. Basic Mixing.

- Avid 2019, p. 1058, 48. Basic Mixing.

- Avid 2019, p. 995–999, 45. Committing, Freezing, and Bouncing Tracks.

- Avid 2019, p. 1000–1002, 45. Committing, Freezing, and Bouncing Tracks.

- Avid 2019, p. 1188–1190, 51. Mixdown.

- Avid 2019, p. 1381, 60. Working with Video in Pro Tools.

- Avid 2019, p. 19–23, 2. Pro Tools Concepts.

- Avid 2019, p. 420–421, 20. Importing and Exporting Session Data.

- Avid 2019, p. 267–270, 14. Track Presets.

- Avid 2019, p. 381, 19. Track Collaboration.

- Avid 2019, p. 1333–1336, 59. Working with Field Recorders in Pro Tools.

- Avid 2019, p. 1341–1346, 59. Working with Field Recorders in Pro Tools.

- Avid 2019, p. 1387, 61. Satellite Link.

- Avid 2019, p. 1397, 62. Pro Tools Video Satellite.

- Avid 2019, p. 1267, 57. Working with Synchronization.

- Thornton, Mike (July 4, 2018). "Pro Tools HD ends - Avid announce Pro Tools 2018.4 and rebrand Pro Tools HD as Pro Tools Ultimate". Production Expert. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- "Pro Tools - Music Editing Software - Comparison". Avid. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- Thornton, Mike (August 9, 2018). "Pro Tools HD Native and HDX Hardware - Do we still need them?". Production Expert. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- Avid 2019, p. 37–40, 5. Pro Tools Systems.

- "Avid Are Changing Pro Tools Pricing On July 1st 2019 - Is This Good Or Bad News For You? | Pro Tools". Production Expert. Retrieved December 17, 2019.

- Thornton, Mike (March 25, 2018). "The History of Pro Tools - 2012 to 2018 | Pro Tools". Production Expert. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- "The History of Pro Tools - 1984 to 1993 | Pro Tools". Production Expert. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- "Digidesign Pro Tools 4". Sound on Sound. July 1997. Archived from the original on June 6, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2018.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Collins 2002, p. 14.

- Collins 2002, p. 13.

- Collins 2002, p. 15.

- Collins 2002, p. 16.

- Collins 2002, p. 17.

- Thornton, Mike (July 2005). "What's new in Pro Tools 6.9". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

- Wherry, Mark (August 2006). "Digidesign Icon". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- "Product news from PLASA: Digidesign VENUE Live Sound Environment, D-Show Mixing Console". Mix Magazine. September 16, 2004. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- Inglis, Sam (November 2005). "Digidesign Mbox 2". Sound on Sound. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- Thornton, Mike (April 2007). "Pro Tools: What's New In 7.3". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- "Digidesign M Box 2 Micro". Sound on Sound. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- "Release dates and versions for Pro Tools (v9 and later)". avid.force.com. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- "Avid HD Omni |". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- "Avid Pro Tools HD Native |". Sound on Sound. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- "Pro Tools 2018.7 Release Notes". avid.force.com. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- "Pro Tools 2018.12 Release Notes". avid.force.com. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- "Pro Tools 2019.5 Release Notes". avid.force.com. Retrieved May 12, 2019.

- "Pro Tools 2019.6 Release Notes". avid.force.com. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- "Pro Tools 2019.10 Release Notes". avid.force.com. February 19, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Pro Tools 2019.12 Release Notes". avid.force.com. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- "Pro Tools 2020.3 Release Notes". avid.force.com. March 24, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- "Pro Tools 2020.5 Release Notes". avid.force.com. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

Bibliography

- Collins, Mike (2002). "2. The Evolution of Pro Tools – A Historical Perspective". Pro Tools for music production: recording, editing and mixing. Oxford: Focal Press. ISBN 978-0-24-051943-2. OCLC 60663870.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manning, Peter (2013). "20. The Personal Computer". Electronic and Computer Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974639-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Milner, Greg (2009). "8: Tubby's Ghost". Perfecting Sound Forever: The Story of Recorded Music. Granta Publications. ISBN 978-1-84708-605-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Battino, David; Richards, Kelli (2005). "Peter Gotcher". The Art of Digital Music: 56 Visionary Artists and Insiders Reveal Their Creative Secrets. San Francisco: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-830-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Avid (2019). Pro Tools Reference Guide (PDF). Avid.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)