Prison–industrial complex

The term "prison–industrial complex" (PIC), derived from the "military–industrial complex" of the 1950s,[1] describes the attribution of the rapid expansion of the US inmate population to the political influence of private prison companies and businesses that supply goods and services to government prison agencies for profit.[2] The most common agents of PIC are corporations that contract cheap prison labor, construction companies, surveillance technology vendors, companies that operate prison food services and medical facilities,[3] correctional officers unions,[4] private probation companies,[3] lawyers, and lobby groups that represent them.

The portrayal of prison-building/expansion as a means of creating employment opportunities and the utilization of inmate labor are particularly harmful elements of the prison-industrial complex as they boast clear economic benefits at the expense of the incarcerated populace. The term also refers to the network of participants who prioritize personal financial gain over rehabilitating criminals. Proponents of this view, including civil rights organizations such as the Rutherford Institute[5] and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU),[6] believe that the desire for monetary gain through prison privatization has led to the growth of the prison industry and contributed to the increase of incarcerated individuals. These advocacy groups assert that incentivizing the construction of more prisons for monetary gain will encourage incarceration, which would affect people of color at disproportionately high rates.[7]

History

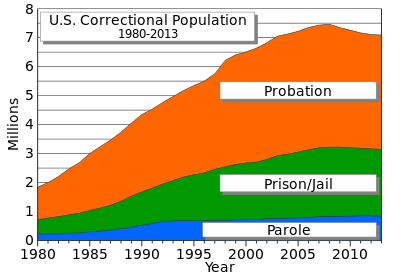

Following the War on Drugs and the passing of harsher sentencing legislation, private sector prisons began to emerge to keep up with the rapidly expanding prison population.[8]

Late 1970s

The Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP) is a federal program that was initiated along with the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and the Prison-Industries Act in 1979.[9] This program legalized the transportation of prison-made goods across state lines and allows prison inmates to earn market wages in private sector jobs that can go towards tax deductions, victim compensation, family support, and room and board.[10] The PIECP, ALEC, and Prison-Industries Act were created with the goal of motivating state and local governments to create employment opportunities that mimic private sector work, generate services that allow offenders to contribute to society, offset the cost of their incarceration, reduce inmate idleness, cultivate job skills, and improve the success rates of transition back into the community after release.[11] Before these programs, prison labor for the private sector had been outlawed for decades to avoid competition. The introduction of prison labor in the private sector, the implementation of PIECP, ALEC, and Prison-Industries Act in state prisons all contributed a substantial role in cultivating the prison-industrial complex.[9] Between the years 1980 through 1994, prison industry profits jumped substantially from $392 million to $1.31 billion.[12]

1980s

In January 1983, the Corrections Corporations of America (CCA) was founded by Nashville businessmen and would grow to become one of the oldest and largest for-profit private prison companies in America, laying the groundwork for a transformation in layout of corrections facilities across the country.[13][14] The 58 was established with the goal of creating public-private partnerships in corrections by substituting government shortcomings with more efficient solutions. The first facility managed by CCA opened in April 1984 in Houston, Texas.[15] As of 2012, the multibillion-dollar corporation, now known as CoreCivic, manages over 65 correctional facilities and boasts of a revenue exceeding over 1.7 billion dollars.[16]

To run the most efficient prisons possible, CCA cut costs by reducing personnel and designing its prisons to include more video cameras for surveillance and clustered cell blocks for easier monitoring. For private prisons, labor is the biggest expense at 70 percent of overall costs, and as a result, CCA and other private prisons have become motivated to cut labor costs by understaffing its prisons.[17]

In 1988, the second largest for-profit private prison corporation, Wackenhut Corrections Corporation (WCC) was established as a subsidiary of The Wackenhut Corporation. The WCC would later develop into GEO Group and as of 2017, their U.S. Corrections and Detention division manages 70 correctional and detention facilities.[18] Their mission statement is as follows:

To develop innovative public-private partnerships with government agencies around the globe that deliver high quality, cost-efficient correctional, detention, community reentry, and electronic monitoring services while providing industry leading rehabilitation and community reintegration programs to the men and women entrusted to our care.[19]

1990s

In 1992, William Barr, then United States Attorney General, authored a report, The Case for More Incarceration, which argued for an increase in the United States incarceration rate.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32]

The passing of mandatory minimum sentencing and truth in sentencing legislature contributed greatly to the exponential growth in the prison population throughout the 1990s.[33] Mandatory minimum sentencing had a disproportionately high effect on the number of African-American and other minority inmates in detention facilities.[34] Throughout the 1990s, the CCA and GeoGroup were both heavily connected to the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), and were recognized for their substantial contributions in 1999.[35]

In 1994, President Bill Clinton passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, the largest crime bill in history.[34] The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act directly allotted an increase of funding of $9.7 billion for prisons and introduced the three-strikes law, which subjected convicts of three offences to exceedingly long sentences (25 year to life minimum), amplifying the effects of mass incarceration and increasing the profit margins of the private specialized corporations such as CCA and GeoGroup and their subsidiaries.[6][7][36] By May 1995, there were over 1.5 million people incarcerated, an increase from 949,000 inmates in 1993.[34]

2000s

From 1984 to 2000, the overall state spending on prisons increased at an alarmingly high rate and from the year 1970 to 2005, the number of inmates in the United States surged by 700 percent.[37] Developments in privatization of prisons continued to progress and by 2003, 44.2% of state prisoners in New Mexico were held in private prison facilities.[8] Other states such as Arizona, Vermont, Connecticut, Alabama, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Utah, Ohio, and Florida also began expanding their private prison contracts.[8] As of 2015, there were 91,300 state inmates and 26,000 federal inmates housed in private prison facilities, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Nationwide, this is 7 percent and 13 percent of inmates, respectively.[38]

In late 2016, the Obama Administration issued an executive policy to reduce the number of private federal prison contracts. On August 18, 2016, then-Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates issued a memorandum that stated: "I am directing that, as each contract [with a private prison corporation] reaches the end of its term, the Bureau should either decline to renew that contract or substantially reduce its scope in a manner consistent with the law and the overall decline of the Bureau's inmate population."[38]

Less than a month into Donald Trump's presidency, Attorney General Jeff Sessions reversed the Obama Administration policy. The Trump Administration has so far increased immigration enforcement and instituted harsher criminal sentences.[38]

Many critics of private prisons argue that prison privatization serves as a large agent for cultivating and feeding into the prison-industrial complex in the United States. John W. Whitehead, constitutional attorney and founder of the Rutherford Institute asserts "Prison privatization simply encourages incarceration for the sake of profits, while causing millions of Americans, most of them minor, nonviolent criminals, to be handed over to corporations for lengthy prison sentences which do nothing to protect society or prevent recidivism"[7] and argues that it characterizes an increasingly inverted justice system dependent upon an advancement in power and wealth of the corporate state.[7]

Private prisons have become a lucrative business, with CCA generating enough revenue that it has become a publicly traded company. Financial institutions have taken notice and are now some of the largest investors in private prisons, including Wells Fargo (which currently has around $6 million invested in CCA), Bank of America, Fidelity Investments, General Electric, and The Vanguard Group.[17]

According to a 2010 investigation by the United States Department of Justice, many of the employees and prisoners were exposed to toxic metals from not being sufficiently trained nor were given the resources to handle toxic material. Injury and illness as a result were not reported to appropriate authorities. When investigated, they found that UNICOR, a prison labor program for inmates within the Federal Bureau of Prisons, had attempted to conceal evidence of working conditions from inspectors by cleaning up the production lines before they arrived.[39][40]

In 2010, both the Geo Group and CoreCivic managed contracts with combined revenues amounting to $2.9 billion.[35] In January 2017, both the Geo Group and CoreCivic welcomed the inauguration of President Trump with generous $250,000 donations to his inaugural committee.[41]

The War on Drugs

The War on Drugs has significantly influenced the development of the prison-industrial complex. The policy measures taken to categorize drug abuse as a criminal issue (rather than a health issue as many advocate) have directly sustained the existence of the prison-industrial complex.[42] Since President Reagan institutionalized the War on Drugs in 1980, incarceration rates have tripled.[43] In fact, the Federal Bureau of Prisons reports that drug offense convictions have led to a majority of the US inmate population in federal prisons.[44]

Some policy analysts attribute the end of the prison-industrial complex to the lessening of prison sentences for drug usage.[45] Some even call for a total shutdown of the War on Drugs itself and believe that this solution will mitigate the profiting incentives of the prison-industrial complex.[46]

History of the relationship between the War on Drugs and the prison-industrial complex

One of the factors leading to the prison-industrial complex began in New York in 1973.[47] Nelson Rockefeller, the governor of New York at the time, rallied for a stringent crackdown on drugs. Rockefeller essentially set the course of action for the War on Drugs and influenced other states' drug policies. For any illegal drug dealer, even a juvenile, he advocated a life-sentence in prison exempt from parole and plea-bargaining.[47] This led to the Rockefeller Drug Laws which, although not as harsh as Rockefeller had called for, encouraged other states to enact similar laws.[47] The federal government further accelerated incarceration, passing the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act. These laws led to overcrowding in New York prisons. Rockefeller was succeeded as governor by Mario Cuomo. Cuomo was forced to support prison expansion because he was unable to generate enough support to dismantle the drug laws. In order to receive funding for these prisons, Cuomo financed this project to the Urban Development Corporation (a public state agency) which, to the benefit of the state government, could issue state bonds without voter support.[47] The Urban Development Corporation legally owned the prisons and the state ended up selling the Attica prison to the corporation.[47] These events led to the recognition of the ability to gain political capital from privatizing prisons.[47]

Impact of drug offense imprisonment on the prison-industrial complex

Policies initiated due to the War on Drugs have led to prison expansion and consequently allowed the prison-industrial complex to thrive.[48] A study states that "The number of persons awaiting trial or serving a sentence for a drug offense in prison or jail has increased from about 40,000 in 1980 to 450,000 today."[48] The significance of creating efficient drug punishment is heightened by the relentless cycle created when imprisoning drug sellers. Even if a drug seller is prosecuted, the drug industry still exists and other sellers take the place of the imprisoned seller. This is described as the "replacement effect".[48] There is a constant supply of drug sellers and hence, a constant supply of potential prison inmates. The War on Drugs has initiated a perpetual cycle of drug dealing and imprisonment. As a result of these events, in many ways, a domino effect has occurred: tough-on-drug policies led to overcrowding in prisons; this was one of the factors which led to the realization of the profiting gain from prison privatization; and this incentive became one of the factors which eventually led to the system now known as the prison-industrial complex.[49]

War on drugs and racialization of the prison-industrial complex

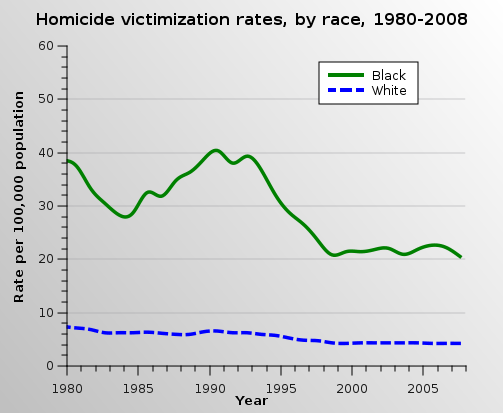

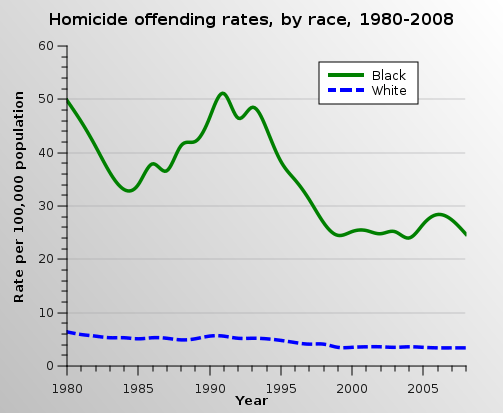

Critics have stated that the War on Drugs has disproportionately targeted African Americans and as a result has also reinforced the institutionalized racism embedded in the prison-industrial complex. Collected data illustrates that "Although the prevalence of illegal drug use among white men is approximately the same as that among black men, black men are five times as likely to be arrested for a drug offense."[47] This racial disparity has led to a prison inmate population with close to a 50% African-American demographic.[47] For further information, see § Minorities.

Economics

Effects

Eric Schlosser wrote an article published in Atlantic Monthly in December 1998 stating that:

The 'prison-industrial complex' is not only a set of interest groups and institutions; it is also a state of mind. The lure of big money is corrupting the nation's criminal-justice system, replacing notions of safety and public service with a drive for higher profits. The eagerness of elected officials to pass tough-on-crime legislation – combined with their unwillingness to disclose the external and social costs of these laws – has encouraged all sorts of financial improprieties.

Schlosser also defined the prison industrial complex as "a set of bureaucratic, political, and economic interests that encourage increased spending on imprisonment, regardless of the actual need".[50]

Hadar Aviram, Professor of Law at UC Hastings, suggests that critics of the prison-industrial complex (PIC) focus too much on private prisons. While Aviram shares their concerns that "private enterprises designed to directly benefit from human confinement and misery is profoundly unethical and problematic", she claims that "the profit incentives that brought private incarceration into existence, rather than private incarceration itself, are to blame for the PIC and its evils". In the neoliberal era, she argues, "private and public actors alike respond to market pressures and conduct their business, including correctional business, through a cost/benefit prism".[51]

Prison labor

The prison industrial complex has an economic stronghold in its inclusion and participation of private businesses that benefit from the exploitation of the prison labor;[52] prison mechanisms remove "un-exploitable" labor, or so-called "underclass", from society and redefine it as highly exploitable cheap labor.[53] Scholars using the term "prison industrial complex" have argued that the trend of "hiring out prisoners" is a continuation of the slavery tradition.[54]

Jobs that are geared toward the prison industry are jobs that require little to no industry-relevant skill, have a large heavy manual labor component and are not high paying jobs.[55] The wages for these jobs Is typically minimum wage, where as the in house prison jobs pay $0.12 to $0.40 per hour.[56]

Criminologists have identified that the incarceration is increasing independent of the rate of crime. The use of prisoners for cheap labor while they are serving time ensures that some corporations benefit economically.[55]

As the prison population grows, a rising rate of incarceration feeds small and large businesses such as providers of furniture, transportation, food, clothes and medical services, construction and communication firms.[57] Furthermore, the prison system is the third largest employer in the world. Prison activists who dispute the existence of a prison industrial complex have argued that these parties have a great interest in the expansion of the prison system since their development and prosperity directly depends on the number of inmates.[57] They liken the prison industrial complex to any industry that needs more and more raw materials, prisoners being the material.[57]

Activists Eve Goldberg and Linda Evans report in Masked Racism: Reflections on the Prison Industrial Complex by Angela Davis that "For private business, prison labor is like a pot of gold. No strikes. No union organizing. No health benefits, unemployment insurance, or workers' compensation to pay. No language barriers, as in foreign countries. New leviathan prisons are being built on thousands of eerie acres of factories inside the walls. Prisoners do data entry for Chevron, make telephone reservations for TWA, raise hogs, shovel manure, make circuit boards, limousines, waterbeds, and lingerie for Victoria's Secret -- all at a fraction of the cost of 'free labor'."[58]

Corporations, especially those in the technology and food industries, contract prison labor, as it is legal and often completely encouraged by government legislature.[59] The Work Opportunity Tax Credit (WOTC) serves as a federal tax credit that grants employers $2,400 for every work-release employed inmate.[60] "Prison insourcing" has increasingly grown in popularity as the cheaper alternative to outsourcing with a wide variety of companies such as McDonald's, Target, IBM, Texas Instruments, Boeing, Nordstrom, Intel, Wal-Mart, Victoria's Secret, Aramark, AT&T, BP, Starbucks, Microsoft, Nike, Honda, Macy's and Sprint and many more actively participating in prison insourcing throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

Statistics show that the unemployment rate is correlated to the incarceration rate. The prison system is easily manipulated and geared to help support the most economically advantageous situation.[55] With more prisoners comes more free labor. When having larger privatized prisons makes it cheaper to incarcerate each individual and the only side effect is having more free labor, it is extremely beneficial for companies to essentially rent out their facilities to the state and the government.[61] Private or for profit prisons have an incentive in making decisions in regards to cutting costs while generating a profit. One method for this is using prison inmates as a labor force to perform production work.[39][40]

Advocates of prison labor cite that rehabilitation is promoted through discipline, a strong work ethic, and providing inmates with valuable skills to be used upon release.[62] Gina Honeycutt, executive director of the National Correctional Industries Association stated, "Many offenders have never worked a legal job and need to learn the basics like showing up on time, listening to a supervisor and working as part of a team."[56] Studies have also shown that participants in prison labor programs often have a lower risk of recidivism, showing that graduates of the program are less likely to be repeat offenders on average.[56] Honeycutt also stated, "In recent years, the focus of many work programs has shifted to concentrate even more on effective rehabilitation of inmates. The transition in the last five years has been away from producing a product to producing a successful offender as our product."[56]

Cynthia Young states that prison labor is an "employers' paradise".[63] Prison labor can soon deprive the free labor of jobs in a number of sectors, since the organized labor turns out to be un-competitive compared to the prison counterpart, attributed to the crowding-out effect.[63]

Journalist Jonathan Kay in the National Post defined the "prison industrial complex" as a "corrupt human-warehousing operation that combines the worst qualities of government (its power to coerce) and private enterprise (greed)". He states that inmates are kept in inhumane conditions and that the need to preserve the economic advantage of a full prison leads prison leaders to thwart any effort or reforms that might reduce recidivism and incarcerations.[54]

Investments

In a Bureau of Prisons (BOP) funded study by Doug McDonald. and Scott Camp, known as the "Taft Studies", privatized prisons were compared side-to-side with the public prisons on economic, performance, and quality of life for the prisoner scales.[64] The study found that in a trade off for allowing prisons to be more cheaply run and operated, the degree to which prisoners are reformed goes down. Because the privatized prisons are so much larger than the public-run prisons, they were subject to economies of scale.[64] Privatized prisons run on business models, promoting more an efficient, accountable, lower cost alternative to decrease government spending on incarceration.[62]

In 2011, The Vera Institute of Justice surveyed 40 state correction departments to gather data on what the true cost of prisons were. Their reports showed that most states had additional costs ranging from one percent to thirty-four percent outside of what their original budget was for that year.[65]

In 2016, during President Obama's administration private prisons were on the decline, as they were considered more expensive and less safe than government-run facilities.[66] Former Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates stated, "Private prisons simply do not provide the same level of correctional services, programs, and resources; they do not save substantially on costs; and as noted in a recent report by the Department's Office of Inspector General, they do not maintain the same level of safety and security."[66] Private prison stocks were at their lowest point since 2008 and on August 18, 2016, the United States Justice Department noticed a declining reliance on private prisons and was developing a plan to phase out its use of private prisons.[67]

The stock prices of the largest private prison operations, CoreCivic and Geo Group, skyrocketed in 2016 following the election of President Trump, with CoreCivic experiencing a 140% increase and Geo Group rising 98%.[66] Attorney General Jeff Sessions stated in a February 21, 2017 memo that the Obama administration had "impaired the U.S. Bureau of Prison's ability to meet the future needs of the correctional system" and rescinded the Obama directive that would curtail the government use of private prisons.[67] In 2017, CNN attributed this rise of private prison stock to President Trump's commitment to lowering crime and toughening immigration, translating to more individuals to be arrested, therefore leading to an increase of private prison profits.[66] Both companies donated heavily to the Trump election campaign in 2016.[66]

Immigration

Funding of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) is increasing as about a total of $4.27 billion was allotted to the INS in the 2000 fiscal budget. This is 8% more than in the 1999 fiscal budget.[68] This expansion, experts claim, has been too rapid and thus has led to an increased chance on the part of faculty for negligence and abuse.[69][70] Lucas Guttengag, director of the ACLU Immigrants' Rights Project stated that, "immigrants awaiting administrative hearings are being detained in conditions that would be unacceptable at prisons for criminal offenders".[68] Such examples include "travelers without visas" (TWOVs) being held in motels near airports nicknamed "Motel Kafkas" that are under the jurisdiction of private security officers who have no affiliation to the government, often denying them telephones or fresh air, and there are some cases where detainees have been shackled and sexually abused according to Guttengag.[68] Similar conditions arose in the ESMOR detention center at Elizabeth, New Jersey where complaints arose in less than a year, despite having a "state-of-the-art" facility.[68]

The number of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. is 11.3 million.[71][72] Those that argue against the PIC claim that effective immigration policy has failed to pass since private detention centers profit from keeping undocumented immigrants detained.[72] They also claim that despite having the incarceration rate grow "10 times what it was prior to 1970", "it has not made this country any safer"' Since the September 11 attacks in 2001, the budget for Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), have nearly doubled from 2003 to 2008, with CBP's budget increasing from $5.8 billion to $10.1 billion and ICE from $3.2 billion to $5 billion and even so there has been no significant decrease in immigrant population.[72] Professor Wayne Cornelius, professor Emeritus of Political Science at UC San Diego, even argued that it is so ineffective that "92–97%" of immigrants who attempt to cross in illegally "keep trying until they succeed", and that such measures actually increase the risk and cost of travel, leading to longer stays and settlement in the US.[72]

There are around 400,000 immigrant detainees per year, and 50% are housed in private facilities. In 2011, CCA's net worth was $1.4 billion and net income was $162 million. In this same year, The GEO Group had a net worth of $1.2 billion and net income of $78 million. As of 2012, CCA has over 75,000 inmates within 60 facilities and the GEO Group owns over 114 facilities.[73] Over half of the prison industry's yearly revenue comes from immigrant detention centers. For some small communities in the Southwestern United States, these facilities serve as an integral part of the economy.[74][75] According to Chris Kirkham, this constitutes part of a growing immigration industrial complex: "Companies dependent upon continued growth in the numbers of undocumented immigrants detained have exerted themselves in the nation's capital and in small, rural communities to create incentives that reinforce that growth."[74] A study by the ACLU says that many are housed in inhumane conditions as many facilities operated by private companies are exempt from government oversight, and studies are made difficult as such facilities may not be covered by a Freedom of Information Act.[76]

In 2009, University of Kansas professor Tanya Golash-Boza coined the term, "Immigration Industrial Complex", defining it as "the confluence of public and private sector interests in the criminalization of undocumented migration, immigration law enforcement, and the promotion of 'anti-illegal' rhetoric", in her paper "The Immigration Industrial Complex: Why We Enforce Immigration Policies Destined to Fail".[77]

In 2009, congressional immigration detention policies requires that U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) maintain 34,000 immigration detention beds daily. This immigration bed quota has steadily increased with each passing year, costing ICE around $159 to detain one individual for one day.[78]

In 2010, immigration detention policies implemented by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) benefited the two major private prison corporations CCA and GeoGroup, increasing their share of immigrant detention beds by 13%.[79] Compared to data from 2009, the percentage of ICE immigrant detention beds in the United States are owned and operated by private for-profit prison corporations has increased by 49%, with CCA and GeoGroup operating 8 out of 10 of the largest facilities.[79] Although the combined revenues of CCA and GEO Group were about $4 billion in 2017 from private prison contracts, their number one customer was ICE.[80]

Impact and response

Women

In 1994, UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women was released which stated that "Among many other abuses women prisoners have identified, are pat searches (male guards pat searching and groping women), illegal strip searches (male guards observing strip searches of women), constant lewd comments and gestures, violations of their right to privacy (male guards watching women in showers and toilets), and in some instances, sexual assault and rape." International human rights standards reinforce this by stating "the rape of a women in custody is an act of torture".[81] In addition, some prisons fail to meet women's needs with providing basic hygiene and reproductive health products.[82]

In regards to women and the prison-industrial complex, Angela Davis stated that "State-sanctioned punishment is informed by patriarchal structures and ideologies that have tended to produce historical assumptions of female criminality linked to ideas about the violation of social norms defining a 'woman’s place'. Considering the fact that as many as half of all women are assaulted by their husbands or partners combined with dramatically rising numbers of women sentenced to prison, it may be argued that women in general are subjected to a far greater magnitude of punishment than men."[83] She also suggested that the "historical and philosophical connections between domestic violence and imprisonment [comprise] two modes of gendered punishment – one located in the private realm, the other in the public realm".[84]

Angela Davis continues to argue: "the sexual abuse of women in prison is one of the most heinous state-sanctioned human rights violations within the United States today. Women prisoners represent one of the most disenfranchised and invisible adult populations in our society. The absolute power and control the state exercises over their lives both stems from and perpetuates the patriarchal and racist structures that, for centuries, have resulted in the social domination of women."[84]

According to Angela Davis and Cassandra Shaylor in their research entitled "Race, Gender, and the Prison-Industrial Complex", most women in prison experience some degree of depression or post-traumatic stress disorder.[81] Very often they are neither diagnosed nor treated, with injurious consequences for their mental health in and out of prison. Many women report that when requesting counseling, they are offered psychotropic medications instead. As technologies of imprisonment become increasingly repressive and practices of isolation become increasingly routine, mentally ill women often are placed in solitary confinement, which can only exacerbate their condition.[81]

Minorities

70 percent of the United States prison population is composed of racial minorities.[86] Due to a variety of factors, different ethnic groups have different rates of offending, arrest, prosecution, conviction and incarceration. In terms of percentage of ethnic populations, in descending order, the U.S. incarcerates more Native Americans, African Americans, followed by Hispanics, Whites, and finally Asians. Native Americans are the largest group incarcerated per capita.[86]

Response

A 2014 report by the American Friends Service Committee, Grassroots Leadership, and the Southern Center for Human Rights claims that recent reductions in the number of people incarcerated has pushed the prison industry into areas previously served by non-profit behavioral health and treatment-oriented agencies, referring to it as the "Treatment Industrial Complex", which "has the potential to ensnare more individuals, under increased levels of supervision and surveillance, for increasing lengths of time – in some cases, for the rest of a person's life".[87] Sociologist Nancy A. Heitzeg and activist Kay Whitlock claim that contemporary bipartisan reforms being proposed "are predicated on privatization schemes, dominated by the anti-government right and neoliberal interests that more completely merge for-profit medical treatment and other human needs supports with the prison-industrial complex".[88]

Sociologist Loïc Wacquant of UC Berkeley is also dismissive of the term for sounding too conspiratorial and for overstating its scope and effect. However Bernard Harcourt, Professor of Law at Columbia University, considers the term useful insofar as "it highlights the profitability of prison building and the employment boom associated with prison guard labor. There is no question that the prison expansion served the financial interests of large sectors of the economy."[2]

Another writer of the era who covered the expanding prison population and attacked "the prison industrial complex" was Christian Parenti, who later disavowed the term before the publication of his book, Lockdown America (2000). "How, then, should the left critique the prison buildup?" asked The Nation in 1999:

Not, Parenti stresses, by making slippery usage of concepts like the 'prison–industrial complex'. Simply put, the scale of spending on prisons, though growing rapidly, will never match the military budget; nor will prisons produce anywhere near the same 'technological and industrial spin-off'.

Prisons in the U.S. are becoming the primary response to mental illness among poor people. The institutionalization of mentally ill people, historically, has been used more often against women than against men.[81]

Reform

Prison abolition movement

A response to the prison industrial complex is the prison abolition movement.[89] The goal of prison abolition is to end the prison industrial complex by eliminating prisons.[90] Prison abolitionists aim to do this by changing the socioeconomic conditions of the communities that are affected the most by the prison-industrial complex. They propose increasing funding of social programs in order to lower the rate of crimes, and therefore eventually end the need for police and prisons.

Alternatives to detention

Due to the overcrowding in prisons and detention centers by for-profit corporations, organizations such as Amnesty International, propose using alternatives such as reporting requirements, bonds, or the use of monitoring technologies.[91] The questions often brought up with alternatives include whether they are effective or efficient. A study published by the Vera Institute attempts to answer this question by stating that when alternatives such as monitoring technologies were used, they found that 91% of the individuals appeared at their court date.[91] The Institute recorded that the relative cost of using such alternatives has been estimated at $12 per day[91] a relatively low price in comparison to the reported average cost of incarceration in the U.S., which has been priced at roughly $87.61 per day.[92]

Despite the relative efficiency and effectiveness of alternative to detention, there is still much debate that these alternatives will not change the dynamics of incarceration. This argument lies in the fact that major corporations such as the GEO Group and Corrections Corporations of America will still be profiting by simply re-branding and moving towards rehabilitation services and monitoring technologies.[93] Rather than effectively ending and finding a solution to the PIC, more people will simply find themselves imprisoned by another system.[93] Other opposition to alternatives comes from the public. According to Ezzat Fattah, opposition towards prison alternatives and correctional facilities is due to the public fearing having that having these facilities in their neighborhoods will threaten the security and integrity of their communities and children.[94]

Critical Resistance

The movement gained momentum in 1997, when a group of prison abolition activists, scholars, and former prisoners collaborated to organize a three-day conference to examine the prison-industrial complex in the U.S. The conference, Critical Resistance to the prison-industrial complex, was held in September 1998 at the University of California, Berkeley and was attended by over 3,500 people of diverse academic, socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. Two years after the conference, a political grassroots organization was founded bearing the same name with the mission to challenge and dismantle the prison-industrial complex.[95]

In 2001, the organization adopted a national structure with local chapters in Portland, Los Angeles, Oakland, and New York City to develop campaigns and projects working towards abolishing the prison industrial complex.[96] Currently, the cause has shifted towards supporting efforts towards resisting state repression and developing tools to re-imagine life without the prison industrial complex.[96]

In 2010, at the U.S. Social Forum, committed activists joined together to discuss prison justice and stated that "Because we share a vision of justice and solidarity against confinement, control, and all forms of political repression, the prison industrial complex must be abolished."[97] Following the forum, the rise of Formerly Incarcerated, Convicted People's Movement helped to incorporate abolition into other movements such as Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, and the Movement for Black Lives.[97]

School-to-prison pipeline reform

A competing explanation for the disproportionate arrest and incarceration of people of color and persons with lower socioeconomic status is the school-to-prison pipeline, which generally proposes that practices in public schools (such as zero-tolerance policies, police in schools, and high-stakes testing) are direct causes of students dropping out of school and, subsequently, committing crimes which lead to their being arrested.[98] 68% of state prisoners had not completed high school in 1997, including 70 percent of women state prisoners. Suspension, expulsion, and being held back during middle school years are the largest predictors of arrest for adolescent women.[99] The school-to-prison pipeline disproportionately affects young black men with an overall incarceration risk that is six to eight times higher than young whites. Black male high school dropouts experienced a 60% risk of imprisonment as of 1999.[100] There is a recent trend of authors describing the school-to-prison pipeline as feeding into the prison-industrial complex.[101]

Since the shortcomings of zero-tolerance discipline have grown very clear, there has been a widespread movement to support reform across school districts and states.[102] Growing research that shows suspensions, especially for minor infractions and misbehavior, are a flawed disciplinary response has encouraged many districts to adopt new disciplinary alternatives.[102] In 2015, mayor of New York City Bill de Blasio joined with the Department of Education to address school discipline in a campaign to tweak the old policies. Blasio also spearheaded a leadership team on school climate and discipline to take recommendations and craft the foundations for more substantive policy.[102] The team released recommendations that work towards reducing the racial disparity in suspension and discussing the underlying root cause of disciplinary infractions through restorative justice.[102]

See also

- Angela Davis

- Convict lease

- Kids for cash scandal

- List of countries by incarceration rate

- United States Incarceration Rate

- List of U.S. states by incarceration rate

- Mentally ill people in United States jails and prisons

- Military–industrial complex

- Race in the United States criminal justice system

References

- Selman, Donna; Leighton, Paul (2010). Punishment for Sale: Private Prisons, Big Business, and the Incarceration Binge. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 78. ISBN 978-1442201736.

- Harcourt, Bernard (2012). The Illusion of Free Markets: Punishment and the Myth of Natural Order. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674066162 p. 236

- Alex Friedmann (15 January 2012). The Societal Impact of the Prison Industrial Complex, or Incarceration for Fun and Profit—Mostly Profit. Prison Legal News. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Arria, Michael (September 27, 2017). "Prison Guard Unions Play a Key Role in Expanding the Prison-Industrial Complex". Truthout. Retrieved April 22, 2018.

- Whitehead, John (April 10, 2012). "Jailing Americans for Profit: The Rise of the Prison Industrial Complex". Rutherford Institute. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- Shapiro, David. "Banking on Bondage: Private Prisons and Mass Incarceration" (PDF). American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved June 29, 2013.

- Whitehead, John W. (April 10, 2012). "Jailing Americans for Profit: The Rise of the Prison Industrial Complex". Huffington Post. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- Mason, Cody (January 2012). "Too Good to be True: Private Prisons in America". The Sentencing Project: 2–4.

- Elk, Mike (August 2011). "The Hidden History of ALEC and Prison Labor". The Nation. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- "Prison Industry Enhancement Certificate Program (PIECP)". The Council of State Governments Justice Center. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- "Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program (PIECP)". National Correctional Industries Association. National Correctional Industries Association. December 16, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- Reyes, Cazzie. "State-Imposed Forced Labor: History of Prison Labor in the U.S". End Slavery Now. National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- Schlosser, Eric. "The Prison-Industrial Complex". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- "CCA - Our History". CCA. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- "CCA - Our History". CCA.

- "The Dirty Thirty: Nothing to Celebrate About 30 Years of Corrections Corporation of America". Grassroots Leadership. June 17, 2013. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- "Redirecting…". heinonline.org. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- "Management and Operations". www.geogroup.com. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- "Who We Are". www.geogroup.com. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- "Info" (PDF). www.ncjrs.gov.

- "Opinion - William Barr would be a terrible AG. And Mueller's got nothing to do with it". NBC News.

- Stewart, Emily (January 14, 2019). "William Barr, Trump's nominee for attorney general, heads to the Senate on Tuesday". Vox.

- "William Barr's record on 4 key issues". PBS NewsHour. December 7, 2018.

- Higgins, Tucker (January 15, 2019). "Voting rights groups are concerned about Trump AG nominee William Barr". www.cnbc.com.

- "Where William Barr stands on the issues, then and now". PBS NewsHour. January 15, 2019.

- Wiener, Jon (December 13, 2018). "William Barr: Worse Than Jeff Sessions?". The Nation – via www.thenation.com.

- "AG nominee William Barr pledges to protect Mueller's work, but may not make it public". www.newstatesman.com.

- "Latino groups closely following William Barr's nomination for attorney general". NBC News.

- Fang, Lee (December 8, 2018). "Trump's Pick for Attorney General Pushed for Military Strikes on Drug Traffickers, Questioned Asylum Law".

- "Tough-on-crime record trails U.S. attorney general nominee into..." Reuters. January 11, 2019 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Barr's Record On Mass Incarceration Comes Under Scrutiny In Confirmation Hearing". NPR.org.

- Mark, Michelle. "Attorney general nominee William Barr helped write the handbook on mass incarceration in the 1990s — but he says he realizes times have changed". Business Insider.

- "Banking on Bondage: Private Prisons and Mass Incarceration". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- John, Arit. "A Timeline of the Rise and Fall of 'Tough on Crime' Drug Sentencing". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- Mason, Cody (January 2012). "Too Good to be True: Private Prisons in America". The Sentencing Project: 12.

- Lussenhop, Jessica (April 18, 2016). "Why is Clinton crime bill so controversial?". BBC News. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- "Banking on Bondage: Private Prisons and Mass Incarceration". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved October 23, 2017.

- "Redirecting…". heinonline.org. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- Thompson, Heather Ann (September 1, 2012). "The Prison Industrial Complex". New Labor Forum. 21 (3): 41–43. doi:10.4179/nlf.213.0000006. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- Grossman, Elizabeth (November 21, 2005). "Toxic Recycling". Nation. 281 (17): 21–24. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- Tseng, Story by Eli Watkins and Sophie Tatum; Graphics by Joyce. "Private prison industry sees boon under Trump". CNN. Retrieved October 22, 2017.

- Cummings, André Douglas Pond (2012). ""All eyez on me": America's war on drugs and the prison-industrial complex". The Journal of Gender, Race, and Justice. 15: 441 – via ProQuest.

- "War on Drugs: How Private Prisons are Using the Drug War to Generate More Inmates". Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Whitehead, John W. (April 10, 2012). "Jailing Americans for Profit: The Rise of the Prison Industrial Complex". Huffington Post. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Cummings, André Douglas Pond. ""All Eyez on Me": America's War on Drugs and the Prison-Industrial Complex". The Journal of Gender, Race, and Justice. 15: 447 – via ProQuest.

- Amensty International (March 26, 2011). "JAILED WITHOUT JUSTICE: IMMIGRATION DETENTION IN THE USA". Amnesty International. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Schlosser, Eric. "The Prison-Industrial Complex". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Mauer, Marc. "Thinking About Prison and its Impact in the Twenty-First Century" (PDF). Walter C. Reckless Memorial Lecture: 613.

- Price, Byron E.; Riccucci, Norma M. (July 26, 2016). "Exploring the Determinants of Decisions to Privatize State Prisons". The American Review of Public Administration. 35 (3): 223–235. doi:10.1177/0275074005277174.

- Schlosser, Eric (December 1998). "The Prison–Industrial Complex". The Atlantic Monthly.

- Hadar Aviram (September 7, 2014). "Are Private Prisons to Blame for Mass Incarceration and its Evils? Prison Conditions, Neoliberalism, and Public Choice". University of California, Hastings College of the Law. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- Guilbaud, Fabrice. "Working in Prison: Time as Experienced by Inmate-Workers". Revue française de sociologie 51.5 (2010): 41-68.

- Smith, Earl; Angela Hattery (2006). "If We Build It They Will Come: Human Rights Violation and the Prison Industrial Complex" (PDF). Society Without Borders. 2 (2): 273–288. doi:10.1163/187219107x203603.

- Kai, Jonathan (March 23, 2013). "The disgrace of America's prison-industrial complex". National Post. p. A22. Retrieved May 28, 2013.

- Chang, Tracy F. H.; Thompkins, Douglas E. (2002). "Corporations Go to Prisons: The Expansion of Corporate Power in the Correctional Industry". Labor Studies Journal. 27 (1): 45–69. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.6544. doi:10.1177/0160449x0202700104.

- Shemkus, Sarah (December 9, 2015). "Beyond cheap labor: can prison work programs benefit inmates?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Goldberg, Evans (2009). Prison Industrial Complex and the Global Economy. Oakland: РM Prеss. ISBN 978-1-60486-043-6.

- Davis, Angela (Fall 1998). "Masked Racism: Reflections on the Prison Industrial Complex". ColorLines.

- "These 5 Everyday Companies Are Profiting from the Prison-Industrial Complex". Groundswell. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- "Work Opportunity Tax Credit". www.doleta.gov. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- "Cost, Performance Studies Look at Prison Privatization". National Institute of Justice: Criminal Justice Research, Development and Evaluation.

- Morrell, Alythea S., "Incentives to Incarcerate: Corporation Involvement in Prison Labor and the Privatization of the Prison System" (2015). Master's Projects. Paper 263.

- Young, Cynthia (2000). "Punishing Labor: Why Labor Should Oppose the Prison Industrial Complex". New Labor Forum (7).

- "Cost, Performance Studies Look at Prison Privatization". National Institute of Justice. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- Ruth Delaney, Christian Henrichson (February 29, 2012). "The Price of Prisons: What Incarceration Costs Taxpayers". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Long, Heather. "Private prison stocks up 100% since Trump's win". CNNMoney. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- "The federal government is again embracing private prisons. Why?". NBC News. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- Welch, Michael (2000). "The Role of Immigration and Naturalization in the Prison Industrial Complex". Social Justice. 27 (3): 73–77. JSTOR 29767232?.

- Koulish, Robert (January 2007). "Blackwater and the Privatization of Immigration Control". Selected Works: 12–13.

- Boehm, Deborah. Returned: Going and Coming in an Age of Deportation.

- "5 facts about illegal immigration in the U.S." Pew Research Center. April 27, 2017. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Boza-Golash, T. (February 12, 2009). "The Immigration Industrial Complex, Why We Enforce Policies Destined to Fail". Sociology Compass. 3 (2): 295–309. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00193.x.

- Ackerman, Alissa R.; Furman, Rich (2013). "The criminalization of immigration and the privatization of the immigration detention: implications for justice". Contemporary Justice Review. 16 (2): 251–263. doi:10.1080/10282580.2013.798506.

- Chris Kirkham (7 June 2012). Private Prisons Profit From Immigration Crackdown, Federal And Local Law Enforcement Partnerships. The Huffington Post. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Christina Sterbenz (27 January 2014). The For-Profit Prison Boom In One Worrying Infographic. Business Insider. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- Evan Hill (June 10, 2014). "Immigrants mistreated in 'inhumane' private prisons, finds report". Al Jazeera America. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- Stribley, Robert (June 28, 2017). "What Is The 'Immigration Industrial Complex'?". Huffington Post. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "Detention Bed Quota". National Immigrant Justice Center. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- "Payoff: How Congress Ensures Private Prison Profit with an Immigrant Detention Quota". Grassroots Leadership. April 1, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

- Conlin, Michelle; Cooke, Kristina (January 18, 2019). "$11 toothpaste: Immigrants pay big for basics at private ICE lock-ups". www.reuters.com. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- Davis, Angela Y., Shaylor, Cassandra. "Race, Gender, and the Prison Industrial Complex California and Beyond". In: Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism Vol.2 Issue 1. (2001): pp. 1–25. Project MUSE. Web. November 1, 2017

- Chandler, Cynthia. "Death and Dying In America: The Prison Industrial Complex's on Women's Health." Berkeley Women's Law Journal. Vol. 18 (2003) 40.Complementary Index. Web. Nov 1. 2017

- "130560266-Frontline-Feminisms-Women-War-and-Resistance-Gender-Culture-and-Global-Politics.pdf". Google Docs. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- Garcilazo, Rebeca (March 2, 2017). "Let's Not Forget About the Women in the Prison–Industrial Complex". Medium. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- Cooper, Alexia D.; Smith, Erica L. (November 16, 2011). Homicide Trends in the United States, 1980-2008 (Report). Bureau of Justice Statistics. p. 11. NCJ 236018. Archived from the original on March 30, 2018.

- "Masked Racism: Reflections on the Prison Industrial Complex". www.historyisaweapon.com. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- Michael King (November 24, 2014). Private Prisons Seek Broader Markets. The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved December 3, 2014. See also: Treatment Industrial Complex: How For-Profit Prison Corporations are Undermining Efforts to Treat and Rehabilitate Prisoners for Corporate Gain. American Friends Service Committee, November 2014.

- Kay Whitlock and Nancy A. Heitzeg (February 24, 2015). "Bipartisan" Criminal Justice Reform: A Misguided Merger. Truthout. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- Davis, Angela. Are Prisons Obsolete?.

- Spade, Dean. Normal Life.

- Amnesty International (March 26, 2011). "Jailed Without Justice: Immigration Detention in the USA". Amnesty International. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- "Annual Determination of Average Cost of Incarceration". Federal Register. July 19, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Holland, Joshua (August 23, 2016). "Private Prison Companies Are Embracing Alternatives to Incarceration". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Ezzat A. Fattah (1982). "Public Opposition to Prison Alternatives and Community Corrections: A Strategy for Action". Canadian Journal of Criminology. 24 (4): 371–385. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Braz, Brown; et al. (200). "The History of Critical Resistance". Social Justice. 27 (3): 6–10. JSTOR 29767223.

- "What is the PIC? What is Abolition?". Critical Resistance. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- "What Abolitionists Do". Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- Wald, Johanna; Losen, Daniel J. (2003). "Defining and Redirecting a School-to-Prison Pipeline". New Directions for Youth Development. 2003 (99): 9–15. doi:10.1002/yd.51. PMID 14635431.

- Wald, Johanna; Losen, Daniel (2003). "Defining and Redirecting a School-to-Prison Pipeline". New Directions for Youth Development. 2003 (99): 9–15. doi:10.1002/yd.51. PMID 14635431.

- Pettit, Becky; Western, Bruce (2004). "Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course: Race and Class Inequality in U.S. Incarceration". American Sociological Review. 69 (2): 151–169. doi:10.1177/000312240406900201. JSTOR 3593082.

- McGrew, Ken (June 1, 2016). "The Dangers of Pipeline Thinking: How the School-To-Prison Pipeline Metaphor Squeezes Out Complexity". Educational Theory. 66 (3): 341–367. doi:10.1111/edth.12173. ISSN 1741-5446.

- Anderson, Melinda D. "School Districts Across the U.S. Are Pledging to Reform Their Student Discipline Policies". The Atlantic. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

Further reading

- "CRIMINAL: How Lockup Quotas and 'Low-Crime Taxes' Guarantee Profits for Private Prison Corporations" (PDF). In the Public Interest. September 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 24, 2014.

- Davis, Angela (1999). The Prison Industrial Complex (CD-ROM (Audiobook) ed.). AK Press. ISBN 978-1-902593-22-7.

- Dyer, Joel (2000). The Perpetual Prisoner Machine—How America Profits from Crime. Westview Press, A Member of the Perseus Books Group. ISBN 978-0-8133-3507-0. LC# HV9950.D04

- Hedges, Chris; Conway, Eddie (January 4, 2015). "How Prisons Rip Off and Exploit the Incarcerated". The Real News. p. 1/2.

Chris Hedges and Eddie Conway discuss 'the prison-industrial complex and how it's impacting the lives of prisoners and their families'

- Tesfaye, Sophia (September 17, 2015). "Bernie Sanders declares war on the prison-industrial complex with major new bill". Salon.

- Silverglate, Harvey & Smeallie, Kyle (December 9, 2008). "Jailhouse Bloc: The real reason law-and-order types love mandatory-minimum sentencing? It's money in their pockets". he Boston Phoenix. Boston, MA.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- "Meet the Prison Profiteers. They're Worse than You Think". American Civil Liberties Union.

- "Prison Industrial Complex: News pertaining to the Prison-Industrial Complex". The Huffington Post.

- USA, INCarcerated. Berkeley: Critical Resistance to the Prison Industrial Complex. 1998. (Video from the 1st Critical Resistance conference)