Pride and Prejudice (1940 film)

Pride and Prejudice is a 1940 American film adaptation of Jane Austen's 1813 novel Pride and Prejudice, directed by Robert Z. Leonard and starring Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier. The screenplay was written by Aldous Huxley and Jane Murfin, adapted specifically from the stage adaptation by Helen Jerome in addition to Jane Austen's novel. The film is about five sisters from an English family of landed gentry who must deal with issues of marriage, morality, and misconceptions. The film was released by MGM on July 26, 1940, in the United States and was critically well received. The New York Times film critic praised the film as "the most deliciously pert comedy of old manners, the most crisp and crackling satire in costume that we in this corner can remember ever having seen on the screen."[3]

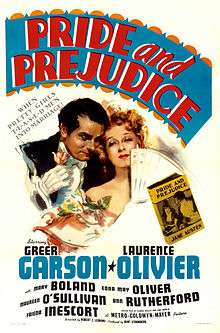

| Pride and Prejudice | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Robert Z. Leonard |

| Produced by | Hunt Stromberg |

| Written by | Helen Jerome (dramatization) |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Pride and Prejudice 1813 novel by Jane Austen |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Herbert Stothart |

| Cinematography | Karl Freund |

| Edited by | Robert Kern |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 117 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1,437,000[1][2] |

| Box office | $1.8 million[1][2] |

Plot

Mrs. Bennet (Mary Boland) and her two eldest daughters, Jane (Maureen O'Sullivan) and Elizabeth (Greer Garson), are shopping for new dresses when they see two gentlemen and a lady alight from a very expensive carriage outside. They learn that the men are Mr. Bingley (Bruce Lester), who has just rented the local estate of Netherfield, and Mr. Darcy (Laurence Olivier), both wealthy, eligible bachelors, which excites Mrs. Bennet. Collecting her other daughters, Mrs. Bennet returns home, where she tries to make Mr. Bennet see Mr. Bingley, but he refuses, having already made his acquaintance.

At the next ball, Elizabeth sees how proud Darcy is when she overhears him refusing to dance with her, and also meets Mr. Wickham, who tells Elizabeth how Darcy did him a terrible wrong. When Darcy does ask her to dance with him, she refuses, but when Wickham asks her in front of Darcy, she accepts.

The Bennets' cousin, Mr. Collins (Melville Cooper), who will inherit the Bennet estate upon the death of Mr. Bennet, arrives, looking for a wife, and decides that Elizabeth will be suitable. At a ball held at Netherfield, he keeps following her around and won't leave her alone. Darcy surprisingly helps her out and later asks her to dance. After seeing the reckless behavior of her mother and younger sisters, however, he leaves her again, making Elizabeth very angry with him once more. The next day, Mr. Collins asks her to marry him, but she refuses point blank. He then becomes engaged to her best friend, Charlotte Lucas (Karen Morley).

Elizabeth visits Charlotte in her new home. There, she is introduced to Lady Catherine de Bourgh (Edna May Oliver), Mr. Collins' "patroness", and also encounters Darcy again. At Charlotte's insistence, Elizabeth sees Darcy who asks her to marry him, but she refuses, partly because of the story Wickham had told her about Darcy, partly because he broke up the romance between Mr. Bingley and Jane, and partly because of his "character". They get into a heated argument and he leaves.

When Elizabeth returns home, she learns that Lydia has run away with Wickham but they were not married. Mr. Bennet and his brother unsuccessfully try to find Lydia. Darcy learns of this and returns to offer Elizabeth his services. He tells her that Wickham will never marry Lydia. He reveals that Wickham had tried to elope with his sister, Georgiana, who was younger than Lydia at the time. After Darcy leaves, Elizabeth realizes she loves him but believes he will never see her again.

Lydia and Wickham return to the house married. A short time later, Lady Catherine arrives and tells Elizabeth that Darcy found Lydia and forced Wickham to marry her by providing Wickham with a substantial sum of money. She also tells her that she can strip Darcy of his wealth if he marries against her wishes. She demands that Elizabeth promise that she will never become engaged to Darcy. Elizabeth refuses. Lady Catherine leaves in a huff and meets outside with Darcy, who had sent her to see Elizabeth to find out if he would be welcomed by her. After Lady Catherine's report, Darcy comes in and he and Elizabeth proclaim their love for each other in the garden. Mr. Bingley also meets Jane in the garden. The movie comes to a close with a long kiss between Elizabeth and Darcy and Mr. Bingley taking Jane's hand, while Mrs. Bennet is spying on both couples and seeing how her other daughters have found good suitors.

Cast

- Greer Garson as Elizabeth Bennet

- Laurence Olivier as Fitzwilliam Darcy

- Mary Boland as Mrs. Bennet

- Edna May Oliver as Lady Catherine de Bourgh

- Maureen O'Sullivan as Jane Bennet

- Ann Rutherford as Lydia Bennet

- Frieda Inescort as Caroline Bingley

- Edmund Gwenn as Mr. Bennet

- Karen Morley as Charlotte Lucas Collins

- Heather Angel as Kitty Bennet

- Marsha Hunt as Mary Bennet

- Melville Cooper as Mr. Collins

- Edward Ashley Cooper as George Wickham

- Bruce Lester as Mr. Bingley

- E. E. Clive as Sir Willam Lucas

- Marjorie Wood as Lady Lucas

- Vernon Downing as Captain Carter

Production

The filming of Pride and Prejudice was originally scheduled to start in October 1936 under Irving Thalberg's supervision, with Clark Gable and Norma Shearer cast in the leading roles.[4] Following Thalberg's death on September 13, 1936, pre-production activity was put on hold. In August 1939, MGM had selected George Cukor to direct the film, with Robert Donat now cast opposite Shearer.[4] The studio had considered filming in England, but these plans were changed at the start of the war in Europe in September 1939, which caused the closure of MGM's England operations. Cukor was eventually replaced by Robert Z. Leonard due to a scheduling conflict.[4]

Reception

The film was critically well received. Bosley Crowther in his review for The New York Times described the film as "the most deliciously pert comedy of old manners, the most crisp and crackling satire in costume that we in this corner can remember ever having seen on the screen." Crowther also praised casting decisions and noted of the two central protagonists:

Greer Garson is Elizabeth—'dear, beautiful Lizzie'—stepped right out of the book, or rather out of one's fondest imagination: poised, graceful, self-contained, witty, spasmodically stubborn and as lovely as a woman can be. Laurence Olivier is Darcy, that's all there is to it—the arrogant, sardonic Darcy whose pride went before a most felicitous fall.[3]

TV Guide, commenting upon the changes made to the original novel by this adaptation, calls the film "an unusually successful adaptation of Jane Austen's most famous novel. Although the satire is slightly reduced and coarsened and the period advanced in order to use more flamboyant costumes, the spirit is entirely in keeping with Austen's sharp, witty portrait of rural 19th century social mores." The reviewer goes on to note:

Garson never did anything better than her Elizabeth Bennet. Genteel but not precious, witty yet not forced, spirited but never vulgar, Garson's Elizabeth is an Austen heroine incarnate. Olivier, too, has rarely been better in a part requiring the passion of his Heathcliff from Wuthering Heights but strapping it into the straitjacket of snobbery.[5]

The review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reported that 100% of critics have given the film a positive review based on 10 reviews, with an average rating of 7.58/10.[6]

Box office

According to MGM records the film earned $1,849,000, resulting in a loss of $241,000, despite the fact that its budget was $1,437,000.[2]

Awards

Pride and Prejudice received an Academy Award for Best Art Direction, Black and White (Cedric Gibbons and Paul Groesse).[7]

Changes from novel

The film differs from the novel in a number of ways. The period of the film, for example, is later than that of Austen's novel—a change driven by the studio's desire to use more elaborate and flamboyant costumes than those from Austen's time period. Production files show that they conflated the fashions of the 1810s to the 1830s. The Motion Picture Production Code prompted some changes in the film as well. Because Mr. Collins, a ridiculous clergyman in the novel, could not seem to criticize men of the cloth, the character was changed to a librarian.[8] Some scenes were altered significantly. For example, Mr. Wickham was introduced at the beginning of the movie. The archery scene was a figment of the filmmakers’ imagination. Also in the confrontation near the end of the film between Lady Catherine de Bourgh and Elizabeth Bennet, the former's haughty demand that Elizabeth promise never to marry Darcy was changed into a hoax to test the mettle and sincerity of Elizabeth's love. In the novel, this confrontation is an authentic demand motivated by Lady Catherine's snobbery and, especially, by her ardent desire that Darcy marry her own daughter.

References

- Glancy, H. Mark "When Hollywood Loved Britain: The Hollywood 'British' Film 1939-1945" (Manchester University Press, 1999)

- The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- Crowther, Bosley (August 9, 1940). "'Pride and Prejudice,' a Delightful Comedy of Manners". The New York Times. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- "Pride and Prejudice: Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- "Pride and Prejudice". TV Guide. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- "Pride and Prejudice (1940)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- "Pride and Prejudice (1940)". The New York Times. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- Looser, Devoney (2017). The Making of Jane Austen. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 129. ISBN 1421422824.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pride and Prejudice (1940 film). |