Prato Cathedral Museum

The Cathedral museum of Prato, Italy was founded in 1967 in a few rooms of the Bishop's residence and in 1976 grew to include items from both the Cathedral of Saint Stephen and the diocesan territory.

Entrance | |

| |

| Established | 1967 |

|---|---|

| Location | Palazzo Vescovile - Piazza Duomo, 49, Prato |

| Type | sacred art, archeology, architecture |

History

The small courtyard that precedes the bishop's residence provides the entrance to the museum which opened in 1967 in the first two rooms. In 1976 the museum was enlarged to accommodate works from the entire diocese including the prestigious reliefs from the pulpit of Donatello. The collection is set up as a diocesan museum.

In 1980 the vaults under the cathedral's transept were added to the museum's space, and other areas were included between 1993-1996, beginning work, only recently concluded, to reconnect the various sections into one single itinerary that passes through a few rooms in the old Palazo dei Proposti, around the harmonious Romanesque cloister, and concluding under the cathedral. A reorganization of the museum space began in 2007, and plans include the preparation of the Renaissance rooms.[1]

Museum itinerary and works

An established itinerary guides the visitor through six rooms containing numerous and varied works of art, passes through an archeological section and the Romaesque cloister, and finishes with the Antiquarium and the vaults.

Room 1: the 13th to the 15th centuries

.jpg)

This room houses important sculptures and paintings (mostly parts of polyptychs) from the 13th to the early 15th centuries from Prato, along with liturgical items from the same era, including:

- Head of Christ (1220-1230), part of an imposing Crucifixione, in polychrome wood, by an anonymous sculptor from Arezzo;

- Madonna enthroned with saints Michael archangel, Peter, and Paul, with Abbot Benventuo who commissioned the work (c. 1262), high-relief sandstone, by Giroldo da Como, from Badia di Montepiano;

- Antiphonary miniature (1270-1280);

- Madonna with child (1310-1330), wood sculpture, by an anonymous Tuscan artist

- Madonna del Parto (c.1320), on wood, by the school of Giotto, from Pieve di Santo Stefano;

- panel from a polyptych depicting the Madonna with child (c.1365) influence of Orcagna, from Carteano;

- two panels with spires from a polyptych with Saints James and John the Baptist (c.1370) by Giovanni Bonsi, from the cathedral;

- Annunciation (c.1410), attributed to Lorenzo di Niccolò, from Pizzidimonte;

- two panels from a polyptych with pairs of saints (Saints Matthew and Saint John, James and Anthony the Abbot), painted on wood (c.1415), by Giovanni Toscani: the central part is preserved in the Philadelphia Museum of Art (USA) and shows four saints;

- chalice and hand-held cross (14th-15th centuries), in gold-plated silver.

The Madonna 'del parto'

The Madonna 'del parto' The Madonna with child, wood sculpture 1310-30

The Madonna with child, wood sculpture 1310-30.jpg) Head of Christ 1220-30

Head of Christ 1220-30_attribuita_a_Lorenzo_di_Niccol%C3%B2.jpg) Annunciation (1410) attributed to Lorenzo di Niccolò

Annunciation (1410) attributed to Lorenzo di Niccolò

Room 2: Sacred liturgical objects

.jpg)

The adjoining room contains items used during liturgical services among which are:

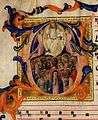

- four gradual illuminations: il Corale D (1429-1430) shows decoration made by Rossello di Jacopo Franchi e Matteo Torelli; il Corale C (1435) illuminated by Meo di Frosino, from Badia di San Fabiano; i Corali B e A (1501) works of Attavante Attavanti;

- Vestment of Saint Stephen (c.1590), in red velvet enriched with embroidered figures on a webbing of gold, donated to the Prato church by cardinal Alessandro de' Medici (later papa Leone XI);

- cope, chasuble and antependium, embroidered, probably based on a design by Giovanni Maria Butteri;

- lavabo (1487), in light stone, by Lorenzo di Salvadore (perhaps based on a design by Giuliano da Sangallo), from the sacristy of the Chapel of the Cintola;

- monstrance (early 18th century), by Bernardo Holzmann, commissioned by Bardi di Vernio.

%2C_di_Lorenzo_di_Salvadore_(forse_su_disegno_di_Giuliano_da_Sangallo).jpg) Lavabo

Lavabo Corale C

Corale C%2C_miniato_da_Rossello_Franchi_e_Matteo_Torelli.jpg) Corale D

Corale D 18th century monstrance

18th century monstrance

Room 3: the Sacred Belt (in Italian Sacra Cintola)

This room is dedicated to works associated with devotion to a precious Marian relic, the Sacred Belt (also known as the Sacred Girdle or the Girdle of Thomas), venerated in Prato from the 12th century:

- The Virgin Mary, assumed into heaven, giving her belt to Saint Thomas the apostole who then passes the belt to a priest (1358-1360), a relief in white marble made for a publit, by the Sienese artist Niccolò del Mercia;

- garment for the statue of the Madonna of the Belt (18th century), with semiprecious stones and embroidery in gold, made in Florence;

- sacred liturgical items (17th - 18th centuries), in silver, belonging to the patrimony of the Chapel of the Belt;

- Dormitio Virginis (1983), plaster model of the antependium, made for the Altar of the Belt by Emilio Greco, after the theft of the 18th century antependium

Archaeological excavations

From the room of the Sacred Belt the visitor can descend to an area partly underground, reaching the archeological section, made to connect the first section of the museum with the rooms along the cloister. The excavation allowed for the recovery of various archeological items, which attest to the habitation of the area from the Etruscans to the Lombards. Of great historical interest:

- fragments of Etruscan ceramics (4th secolo BC), in particular urns, bowls, and jars;

- a burial site (11th century);

- two ovens, maybe for breadmaking (9th-10th centuries).

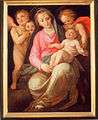

Room 4: the Renaissance

From the archaeological area the visitor can go up into a 15th-century structure, which contains works from the 15th and 16th centuries. Of particular interest:

- Trinity (1435-1440), wood with pinnacles and a background of gold, by Andrea di Giusto Manzini;

- Altar panel depicting a Sacred Conversation showing the Madonna with child with Saints Giusto and Clement (1449), by the Master of the Castello Nativity, perhaps Piero di Lorenzo, in close collaboration with Filippo Lippi;

- Altar panel with the Funeralof Saint Jerome(1453), a masterpiece by Filippo Lippi, commissioned by Geminiano Inghirami for the cathedral;

- Crucifixion (late 15th century), wood painted on both sides, attributed to Sandro Botticelli;

- Saint Luc (c.1480), attributed to Filippino Lippi;

- Annunciation (1509), stained glass, by friar Paolo di Mariotto da Gambassi,

- two panels with The Madonna with child, by Maso da San Friano.

Crucifix attributed to Botticelli

Crucifix attributed to Botticelli%2C_Maestro_della_Nativit%C3%A0_di_Castello.jpg) The Madonna and child with Saints Giusto and Clement (1449), Maestro della Natività di Castello

The Madonna and child with Saints Giusto and Clement (1449), Maestro della Natività di Castello The Madonna with child, Maso da San Friano

The Madonna with child, Maso da San Friano Saint Lucy

Saint Lucy

Room 5: the Pulpit

The room takes its name from the celebrated balcony pulpit made by Donatello for an outside corner of the facade of the cathedral for the solemn showing of the relic of the Sacred Belt:

.jpg)

- the parapet of the external pulpit of the cathedral (1434-1438), made by Donatello and his school. Because of the degradation suffered during their five centuries outside, the reliefs were removed from the pulpit in 1967 and were substituted with replicas. A laborious restoration and cleaning (finished in 1999) directed by the Opificio delle pietre dure of Florence recreated a more unified and legible work. The imposing parapet takes the form of a small round temple with double pilasters that divide it into seven carved sections, each displaying a group of dancing figures which seem to move with joyous and vivacious steps, pictorically rendered thanks to the “stiacciato” (or very low relief) and the reflection of the tessera in the background.

In addition, this room houses:

- the container of the Sacred Belt (1446-1447), made by goldsmith Maso di Bartolomeo, a student of Donatello, in gold-plated copper and bone and reelaborating the donatellan motif of the little angels dancing between the columns of the little temple; this box contained the relic up to 1633 at which time the present silver altar was constructed.

_02.jpg) Maso di Bartolomeo, capsella of the Sacred Belt (1446–48)

Maso di Bartolomeo, capsella of the Sacred Belt (1446–48)- Maso di Bartolomeo, capsella of the Sacred Belt open

Bust in terracotta of Saint Laurence

Bust in terracotta of Saint Laurence Francesco di Simone Ferrucci, The baby Jesus giving a blessing (based on a model of Desiderio da Settignano)

Francesco di Simone Ferrucci, The baby Jesus giving a blessing (based on a model of Desiderio da Settignano)

Room 6: the 17th to the 19th centuries

The following room contains interesting works of art and liturgical object dated from the 17th to the 19th centuries. Of particular importance:

- an altar crucifix, in bronze, made by Antonio Susini, a student of Giambologna;

- Saint Cecilia (1615-1620), painted by Matteo Rosselli;

- The Virgin Mary giving the baby Jesus to Saint Francis of Assisi (c.1619), sketch by Jacopo Chimenti (also called l'Empoli), from the ceiling of the Cathedral of Livorno;

- Guardian angel (1670-1675), oil on canvas, by Carlo Dolci, from the cathedral;

- Saint Peter Alcantara giving communion to Saint Theresa of Avila (1683), oil on canvas, by the Flemish painter Livio Mehus, from the cathedral;

- an altar crucifix (end of the 17th century), in bronze, influenced by Alessandro Algardi;

- a monstrance (1729-1730), made by Lorenzo Loi, from the cathedral;

- Translation of the remains of Saint Stephen (1865), oil on canvas, painted by Alessandro Franchi.

- Matteo Rosselli, Saint Cecilia

.jpg) L'Empoli, the Blessed Virgin and Saint Francis

L'Empoli, the Blessed Virgin and Saint Francis Chalice of Cosimo Merlini

Chalice of Cosimo Merlini%2C.jpg) Carlo Dolci, Guardian angel (1670–75)

Carlo Dolci, Guardian angel (1670–75)

The Romanesque cloister

From the 16th century room the visitor can go up to the Romanesque cloister (late 12th century), in white marble and green serpentine, characterized by original zoomorphic capitals created by the Master of Cabestany.

The Antiquarium and the "vaults"

From the cloister can be reached:

- the burial chapel of the Migliorati (12th century);

- the Antiquarium, in which are found tomb slabs, decorative fragments of the mosaic pavement of the early church (11th and 12th centuries), pieces of capitals, and architectonic fragments of the cloister.

The corridor exits into the "vaults", an underground area proceeding under the transept of the cathedral, used from 1326 to the end of the 18th century for burials from which remain various coats of arms (in stone and painted) and burial insignia.

Contiguous with the "vaults" is the chapel of Saint Stephen (beginning of the 15th century), containing painted murals:

- on the vaults: evangelists and saints (beginning of the 15th century), frescoes, by an anonymous Tuscan painter;

- in the lunettes: The Stoning of Saint Stephen and The Madonna with Saint Stephen and Saint Lorenzo (c.1420), monochrome frescoes, by Pietro and Antonio di Miniato.

Also in the chapel are preserved important relics of the cathedral:

- Reliquary of the torso of Saint Anne (1490), in silver, made by Antonio di Salvi;

- Reliquary of the holy cross (1590), by Egidio Leggi;

- Reliquiario of Saint Stephen (XIX secolo), realizzato su disegno di Alessandro Franchi.

Notes

- From the end of the 1990s the best painted works were joined to the exposition I tesori della città (The treasures of the city) at The Museum of Painted Murals (il Museo di pittura murale )

Bibliography

- Erminia Giacomini Miari, Paola Mariani, Musei religiosi in Italia, Milano 2005, pp. 277–278

- Stefano Zuffi, I Musei Diocesani in Italia. Secondo volume, Palazzolo sull'Oglio (BS) 2003, pp. 40–49

Related links

- Diocese of Prato

- The Prato Cathedral

- Musei diocesani italiani

External links

- "Source: Main website of the Diocese of Prato". diocesiprato.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2012-12-21.

- "The museum on the website of the Comune of Prato". cultura.prato.it (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2007-04-06. Retrieved 2016-10-17.