Potlatch River

The Potlatch River is in the state of Idaho in the United States.[2] About 56 miles (90 km) long, it is the lowermost major tributary to the Clearwater River, a tributary of the Snake River that is in turn a tributary of the Columbia River.[3] Once surrounded by arid grasslands of the Columbia Plateau adjacent to the western foothills of the Rocky Mountains, the Potlatch today is used mainly for agriculture and irrigation purposes.

| Potlatch River | |

|---|---|

The Potlatch near Kendrick | |

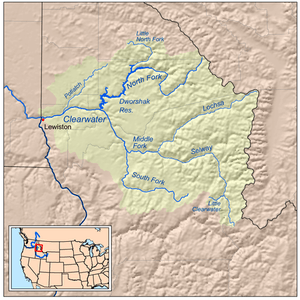

Map of the Clearwater River watershed showing the Potlatch River in the upper left | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Idaho |

| Region | Latah County, Clearwater County, Nez Perce County |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Hoodoo Mountains Confluence of East and West Forks |

| • location | Rocky Mountains, Latah County |

| • coordinates | 46°55′43″N 116°20′55″W |

| • elevation | 2,674 ft (815 m) |

| Mouth | Clearwater River |

• location | Between Myrtle and Spalding, Nez Perce County |

• coordinates | 46°28′31″N 116°46′02″W |

• elevation | 801 ft (244 m) |

| Length | 56 mi (90 km), Northeast-southwest |

| Basin size | 594 sq mi (1,540 km2)[1] |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 379.8 cu ft/s (10.75 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 75 cu ft/s (2.1 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 8,150 cu ft/s (231 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Clearwater River |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Cedar Creek (Idaho) |

| • right | Big Bear Creek |

Its name derives from potlatch, a type of ceremony held by the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest; one such tribe lived along the river for hundreds of years before the arrival of settlers. Pioneers settled the watershed and established farms and ranches in the late 19th century. After that, logging eliminated most of the forests within the watershed and the ecology of the river is still in the process of recovery. Fishing, hiking and camping are popular recreational activities on the river; 14 percent the watershed lies on public lands. Before logging and agriculture, many varieties of riparian and forest plants once populated the catchment, and several species of fish still swim the river and its tributaries.

Course and drainage

The Hoodoo Mountains are the source of the Potlatch River.[4] The Potlatch's course traces a southwesterly line across the eastern Columbia Plateau in the arid Rocky Mountain foothills. Two forks form the river's headwaters in the southern part of the Idaho Panhandle. The West Fork drains part of Latah County and the East Fork is in Clearwater County. These two forks combine near Helmer, and soon the river descends into a canyon that continues all the way to the mouth. While in the canyon, it receives Pine, Big Bear, Middle Potlatch and Little Potlatch Creeks from the north, and Boulder and Cedar Creeks from the south. Idaho State Highway 3 follows part of the lower canyon, and the town of Juliaetta is located at the Middle Potlatch Creek confluence. The river merges with the Clearwater at the elevation of 801 feet (244 m)[2] between the towns of Myrtle and Spalding.[5] Its average discharge at the mouth, according to a USGS stream gauge, is 379.8 cubic feet per second (10.75 m3/s).[6] A peak flow of 8,150 cubic feet per second (231 m3/s) was recorded there in 2006.[7] The river reaches its highest peaks in the winter and early spring, while it reduces to a trickle by summer and autumn.[5] The river mainly flows over and through coarse Columbia River basalts that comprise the Columbia Plateau, similar in geology to the Palouse River farther west.[8]

History

Native Americans of the Nez Perce tribe have lived along the Potlatch River for hundreds of years.[5] The Potlatch River area was once a broad sweep of dry grassland bordered by forested mountains, on the eastern edge of the arid Columbia Plateau. Because of its location just southwest of the foothills of the Rockies, the Potlatch River receives much more rainfall than watersheds just to the west, such as the Palouse and Tucannon Rivers. In 1805 and again in 1806, the Lewis and Clark Expedition passed the mouth of the Potlatch River while traveling down the Clearwater River.[9] They referred to it as "a large creek" and named it Colter's Creek, in honor of John Colter, a member of the expedition. It is not known if they were the first whites to see the river.[8] The modern name of the river was adopted in 1897.[2]

The native environment stayed relatively intact until settlers began to arrive in western Idaho in great numbers in the 1870s, and miners also were attracted by a gold strike at nearby Orofino, on the banks of the Clearwater River.[5] Many of these emigrants set up dryland farms and ranches in the prairies surrounding the Potlatch River. Soil conditions generally improve as one travels southwards through the watershed, but there was a major drawback to growing crops in the southern part of the basin: the inaccessibility of water. Already scarce in the arid Potlatch River drainage, the river's water was hard to reach because of the steep canyon it passes through in most of its lower course. Farmers were restricted to growing crops that did not require irrigation, and many of the lands that did not have access to abundant-enough water were relegated to pasture or hay producing status.[3]

At first, the forests of the watershed were not significantly affected, but after logging operations sprung up near the start of the 20th century, most of the virgin timber in the watershed was cleared. The first sawmills were built to provide lumber for local uses, such as building houses and barns. Soon, however, the Washington, Idaho and Montana Railway extended its tracks into the area, allowing lumber to be exported out of the basin. Logging turned out to be a very profitable industry but had a lasting negative effect on the ecology of the Potlatch River watershed.[3][10]

Splash dams, greased chutes, railroad landings, railroad branch lines and steam donkey operations were among the strategies utilized to exploit the watershed's resources of timber. Unfortunately, railroad embankments and fills used to build up tributaries had artificially straightened them in the process, and erosion increased dramatically on the barren hillside, causing many streams to become much siltier than they naturally would be. Nearly all the old-growth forest in the watershed is now gone, and the forests that remain are mostly second-growth stands.[3]

Ecology

At one time the river's watershed was dominated by grassland mostly consisting of Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass.[5] Cottonwoods, quaking aspen, maple, and alder formed the riparian zone along the Potlatch River. In the foothills, a meadow steppe environment abounding with black hawthorn, snowberry and small conifers flourished, while along the banks of smaller tributaries, hawthorn and mock orange grew. Camas and forbs thrived in the thinly distributed seasonal wetlands along the river and its larger tributary creeks.[3] The forests were mainly a mix of Douglas fir and ponderosa pine, interspersed with rare stands of grand fir, western redcedar, western white pine, and larch,[5] and an understory of oceanspray, ninebark, serviceberry, wild rose and snowberry. Wildfires burned through the watershed from time to time, clearing the way for new growth.[3] After human intervention, these vegetation communities continued to persist, but in lesser numbers, and the grasslands have mostly been wiped out by farming. The average annual precipitation ranges from 15 to 50 inches (380 to 1,270 mm) per year, and annual variations in temperature are around 25 to 100 °F (−4 to 38 °C).[3]

According to a study from 2003–2004, there were 13 different species of fish in the Potlatch River watershed, including speckled dace, longnose dace, rainbow trout (both wild and farm-raised), brook trout, largemouth bass, pumpkinseed, northern pikeminnow, redside shiner, sculpin, bridgelip sucker, largescale sucker, and yellow perch.[11] Migration of steelhead, the anadromous phase of rainbow trout, has been impacted by the construction of dams downstream on the Snake and Columbia Rivers. The two species of dace were cumulatively the largest individual fish population in the watershed, while steelhead accounted for 58.4% of the biomass. Of all the streams sampled during the study, the West Fork Potlatch River had the highest diversity because of its relatively pristine condition. The lower section of the river suffers from chronic pollution caused by agricultural runoff.[11] From 2005 to 2008, the population of steelhead (rainbow) trout in the watershed was recorded by the Potlatch River Steelhead Monitoring and Evaluation Program (PRSME). There was no data for steelhead populations in the main stem but 197 adult steelhead were recorded in the East Fork of the river, while an average of 226 was recorded annually in one of the river's larger tributaries, Big Bear Creek. Over 1,000 steelhead are estimated to return to the Potlatch drainage in strong run years.[12] Outmigration of steelhead smolt from the East Fork was estimated at 6,976 fish while the average for Big Bear Creek was 9,491.[13] The Idaho Department of Fish and Game began a series of seven projects in 2009 in order to conserve fish habitat in the Potlatch.[14]

Land use

Forests cover about 57% of the Potlatch River watershed, while about 38% is used for agriculture and ranching. 78% of the land is privately owned while 14% lie within national forests. 7% is owned by the state, while the Bureau of Land Management and Bureau of Indian Affairs each have a 1% share.[15]

Recreation

Many of the mountainous and forested sections of the drainage basin lie protected under national forest lands. There are several campgrounds overseen by the U.S. Forest Service in the headwaters of the Potlatch River watershed. Fishing is also good in the Potlatch River and many of its tributaries. Anglers are only permitted to catch brook trout, cutthroat trout, and rainbow and steelhead trout. The Department of Fish and Game annually stocks fish in the river.[16] Fishing is permitted on the Potlatch from its mouth upstream to where Moose Creek joins the river near Bovill, as well as on the East Fork.[17]

See also

References

- "Surface Water: Potlatch River Subbasin Assessment and Total Maximum Daily Loads". Water. Idaho Department of Environmental Quality. Archived from the original on 2009-09-30. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- "Potlatch River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1979-06-21. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- "Potlatch River Watershed Management Plan" (PDF). Resource Planning Unlimited. Latah Soil and Water Conservation District. October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-13. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- Mineral Resources of Latah County by Charles R. Hubbard, March 1957

- "Potlatch River Subbasin Assessment and TMDLs" (PDF). Idaho Department of Environmental Quality. September 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-10-02. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- "USGS Gage #133341570 on the Potlatch River near Spalding (Average Streamflow)". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 2004. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- "USGS Gage #133341570 on the Potlatch River near Spalding (Peak Streamflow)". National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 2004. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- "On the Clearwater—Canoe Camp to the Potlatch River". The Volcanoes of Lewis and Clark. U.S. Geological Survey Cascade Volcanoes Observatory. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- Wheeler, Olin Dunbar (1904). The trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1904: A Story of the Great Exploration Across the Continent in 1804-06; With a Description of the Old Trail, Based Upon Actual Travel Over It, and of the Changes Found a Century Later. 2. G. P. Putnam's Sons. p. 122. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- "Lumbering an economic mastery in Clearwater County for almost a century". 20th Century Chronicles. Clearwater Tribune. Archived from the original on 2006-11-09. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- Bowersox, Brett; Brindza, Nathan (2003–2004). "Potlatch River Basin—Fisheries Inventory" (PDF). Idaho Department of Fish and Game. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-01-10. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- https://fishgame.idaho.gov/content/article/potlatch-river-steelhead

- Bowersox, Kent (January 2009). "Production, productivity, and life history characteristics of steelhead, Oncorhynchus mykiss, in the Potlatch River drainage, Idaho" (PDF). The Tippet. Clearwater Fly Casters. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2010-01-27.

- "Direction 2009: Issues, Accomplishments, & Priorities" (PDF). The Compass. Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-01-07. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- "Potlatch River Watershed". Watersheds. Nez Perce Soil and Water Conservation District. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- "Potlatch River". Clearwater National Forest. U.S. Forest Service. Retrieved 2010-01-26.

- "Clearwater Region" (PDF). Fishing Seasons and Rules. Idaho Department of Fish and Game. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-01-30. Retrieved 2010-01-27.