Portola Road Race

The Portola Road Race was an automobile race spanning several cities of Alameda County, California, in 1909 and 1911, the start/finish line positioned in Oakland. The races were held in concert with the Portola Festival celebrating San Francisco's renewal following the devastation of the 1906 earthquake.

1909

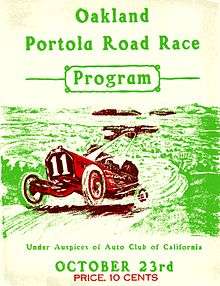

The main race in 1909 ran under the auspices of the Automobile Club of Southern California. It was a little over 254 miles (409 km) long—12 laps of a course laid out over 21.18 mi (34.09 km) which included road segments of Melrose, a settlement newly annexed by Oakland, and San Leandro and Hayward—two communities south of Oakland in Alameda County. An estimated 250,000,[1] 280,000[2] or 300,000[3] people watched the nearly four-hour race. A 24-page race program was published with photographs, advertisements, and a diagram of the race circuit. An article written by Mrs. Frederick J. Linz was included: "Women as well as Men can Motor". First prize was $2,000.[4]

Jack Fleming won the race in car number 4, a four-cylinder, 40-horsepower Pope-Hartford machine that Fleming used to increase his lead to more than one lap over the closest competitor. His average speed of 64.51 mph (103.82 km/h) set a new record for a road race, slightly higher than the most recent results of the Santa Monica Road Race and the Vanderbilt Cup.[1] The fastest lap of the day may have been produced by car number 15, a Stearns driven by Charles Soules who was reported by one newspaper as having clocked in at 18:19 for the 21.18-mile circuit to yield 69.4 mph (111.7 km/h).[3] Another reporter showed Fleming's Pope-Hartford making the fastest lap at 19 minutes flat, a speed of 66.66 mph (107.28 km/h).[1] Second place went to Harris "Harry" Hanshue in car number 13, an Apperson; third place went to Harry Michener driving a Lozier marked as car number 12.[3]

Unusually, the racecourse held three different race events. The first starters were the lightest cars, limited to an engine displacement of 231 to 450 cu in (3,790 to 7,370 cm3)—these cars ran 7 laps. The second group were heavier cars limited to an engine displacement of 451 to 600 cu in (7,390 to 9,830 cm3)—these cars ran 10 laps. The unlimited grand prize race was open to any qualifier who thought they could race 12 laps and win. Each of the cars was started a few minutes after the previous one.[3] Fleming's winning car held an engine that displaced 299.44 cu in (4,906.9 cm3), making it a lightweight contender. He won the first 7-lap event and appeared to be in first place at end of the 10-lap event, even though he was not driving a heavyweight car and thus was not entered in this event. He continued in first place to finish the 12-lap grand prize course.[1]

One spectator death and several injuries occurred because of accidents at the race. A fatal incident happened when a Sunset machine driven by Howard Hall lost a wheel retaining ring while cornering; the metal ring broke the skull of a male spectator,[3] who succumbed several weeks later.[5] Frank Free driving a Knox went off the road on Stanley Avenue near Foothill Boulevard[3] and gravely injured a man who was standing next to his wife-to-be watching the race.[6] She was unharmed. The driver and his mechanic were bruised.[3] Near the southern limit of the racecourse in Hayward, a dog sat down in the middle of the road and was killed by Michener's Lozier.[1]

The grandstands and start/finish line were placed on Foothill Boulevard around Fairfax Avenue and 55th Avenue because Foothill was a long straightaway at that area. In the grandstands could be seen well-known people such as senator George Clement Perkins and Oakland mayor Frank K. Mott. The racecourse was kept clear of spectators by the National Guard of California.[1]

1911

In 1911 the circuit was shortened to 10.923 mi (17.579 km), roughly describing the shape of a quadrilateral with four right-angle turns.[7] The course was described as "tortuous" for the driver, "filled with turns and grades which require frequent gear shifting."[8] The race consisted of three simultaneous events of increasing numbers of laps intended to be 9, 14 and 19.[9] As in 1909, the first starter was a lightweight car with the least engine displacement, followed every few minutes by a car with greater displacement. The lightweight cars ran 9 laps and the heavy cars ran 14 laps. The unlimited grand prize race was to go 19 laps but it was stopped at 15 because of darkness.[7]

The winner of the lightweight race, called the Oakland Trophy, was Charles Bigelow in a 30-horsepower Mercer car averaging 57.3 mph (92.2 km/h).[10] The heavyweight race, called the St. Francis Hotel Trophy, was won by Charlie Merz in a National car averaging 66.8 mph (107.5 km/h).[7][11] The Panama-Pacific Road Race, a "free-for-all" unlimited event, was won by Bert Dingley in a Pope-Hartford; he kept a pace of 65.76 mph (105.83 km/h).[12]

Several injuries were sustained by spectators who crowded the course, forcing drivers to run a narrow gantlet at some points in the race. Post-race criticism observed that civilian police protection of the course was insufficient compared to 1909's National Guard protection. Newly seated California Governor Hiram Johnson refused to call up the National Guard for the race; undeterred, some Guardsmen attempted to provide crowd control in civilian clothing but were not successful.[7]

Race results

| Year | Date | Venue | Winning Driver | Car | Race Distance | Time of Race | Winning Speed | Starting Cars | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miles | Laps | ||||||||

| 1909 | October 23 | various Alameda County roads, 21.18 mi (34.09 km) circuit | Pope-Hartford | 254.16[9] | 12 | 03:58:15 | 64.51 mph | 15 | |

| 1911 | February 22 | various Alameda County roads, 10.923 mi (17.579 km) circuit | Mercer | 98.307 | 9 | 01:42:54 | 57.3 mph | 5 | |

| 1911 | February 22 | various Alameda County roads, 10.923 mi (17.579 km) circuit | National | 152.922 | 14 | 02:17:20 | 66.81 mph | 6 | |

| 1911 | February 22 | various Alameda County roads, 10.923 mi (17.579 km) circuit | Pope-Hartford | 163.845 | 15 | 02:29:30 | 65.76 mph | 5 | |

References

- "World's Record Is Broken in Great Race". The San Francisco Call. 106 (146). October 24, 1909. p. 37.

- "Remarkable Auto Race Records". The Philadelphia Record. January 16, 1910. p. 3.

- "Death Takes Toll in Portola Auto Race". The Bakersfield Californian. 21 (71). October 23, 1909. p. 1.

- Oakland Portola Road Race program, 1909

- "Victim of Flying Auto Tire Dies". The San Francisco Call. December 15, 1909.

- "Road Race Victim Prepares to Marry". The San Francisco Call. January 29, 1910.

- National and Mercer Win. The Automobile. 24. Chilton. March 2, 1911. pp. 640–641.

- "More Motor Racing for Pacific Coast" (PDF). The New York Times. May 19, 1912.

- "Portola Road Race Course". ChampCarStats.com. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- "Oakland Trophy". UltimateRacingHistory.com. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- "St. Francis Hotel Trophy". UltimateRacingHistory.com. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- "Panama-Pacific Road Race". UltimateRacingHistory.com. Retrieved September 7, 2012.