Polyhalogen ions

Polyhalogen ions are a group of polyatomic cations and anions containing halogens only. The ions can be classified into two classes, isopolyhalogen ions which contain one type of halogen only, and heteropolyhalogen ions with more than one type of halogen.

Introduction

Numerous polyhalogen ions have been found, with their salts isolated in the solid state and structurally characterized. The following tables summarize the species found so far.[1][2][3][4][5]

Isopolyhalogen cations Diatomic species *[Cl2]+, [Br2]+, [I2]+ Triatomic species [Cl3]+, [Br3]+, [I3]+ Tetraatomic species [Cl4]+, [I4]2+ Pentaatomic species [Br5]+, [I5]+ Heptaatomic species †[I7]+ Higher species [I15]3+ - * [Cl2]+ can only exist as [Cl2O2]2+ at low temperatures, a charge-transfer complex from O2 to [Cl2]+.[2] Free [Cl2]+ is only known from its electronic band spectrum obtained in a low-pressure discharge tube.[3]

- † The existence of [I7]+ is possible but still uncertain.[1]

Heteropolyhalogen cations Triatomic species [ClF2]+, [Cl2F]+, [BrF2]+, [IF2]+, [ICl2]+, [IBrCl]+, [IBr2]+, [I2Cl]+, [I2Br]+ Pentaatomic species [ClF4]+, [BrF4]+, [IF4]+, [I3Cl2]+ Heptaatomic species [ClF6]+, [BrF6]+, [IF6]+

Isopolyhalogen anions Triatomic species [Cl3]−, [Br3]−, [I3]− Tetraatomic species [Br4]2−, [I4]2− Pentaatomic species [I5]− Heptaatomic species [I7]− Octaatomic species [Br8]2−, [I8]2− Higher species [I9]−, [I10]2−, [I10]4−, [I11]−, [I12]2−, [I13]3−, [I16]2−, [I22]4−, [I26]3−, [I26]4−, [I28]4−, [I29]3−

Heteropolyhalogen anions Triatomic species [ClF2]−, [BrF2]−, [BrCl2]−, [IF2]−, [ICl2]−, [IBrF]−, [IBrCl]−, [IBr2]−, [I2Cl]−, [I2Br]−, [AtBrCl]−, [AtBr2]−, [AtICl]−, [AtIBr]−, [AtI2]− Pentaatomic species [ClF4]−, [BrF4]−, [IF4]−, [ICl3F]−, [ICl4]−, [IBrCl3]−, [I2Cl3]−, [I2BrCl2]−, [I2Br2Cl]−, [I2Br3]−,[I4Cl]−, [I4Br]− Hexaatomic species [IF5]2− Heptaatomic species [ClF6]−, [BrF6]−, [IF6]−, [I3Br4]− Nonaatomic species [IF8]−

Structure

%2B._(ClF2)%2B%2C_(ICl2)%2B.png)

%2B_ion.png)

-_dimer.png)

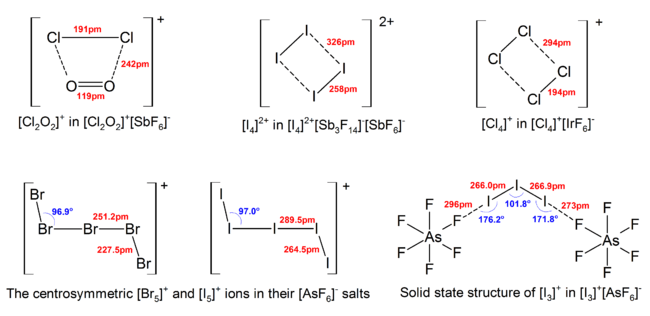

Most of the structures of the ions have been determined by IR spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. The polyhalogen ions always have the heaviest and least electronegative halogen present in the ion as the central atom, making the ion asymmetric in some cases. For example, [Cl2F]+ has a structure of [Cl–Cl–F]− but not [Cl–F–Cl]−.

In general, the structures of most heteropolyhalogen ions and lower isopolyhalogen ions were in agreement with the VSEPR model. However, there were exceptional cases. For example, when the central atom is heavy and has seven lone pairs, such as [BrF6]− and [IF6]−, they have a regular octahedral arrangement of fluoride ligands instead of a distorted one due to the presence of a stereochemically inert lone pair. More deviations from the ideal VSEPR model were found in the solid state structures due to strong cation-anion interactions, which also complicates interpretation of vibrational spectroscopic data. In all known structures of the polyhalogen anion salts, the anions make very close contact, via halogen bridges, with the counter-cations.[4] For example, in the solid state, [IF6]− is not regularly octahedral, as solid state structure of [Me4N]+[IF6]− reveals loosely bound [I2F11]2− dimers. Significant cation-anion interactions were also found in [BrF2]+[SbF6]−, [ClF2]+[SbF6]−, [BrF4]+[Sb6F11]−.[2]

General structures of selected heteropolyhalogen ions Linear (or almost linear) [ClF2]−, [BrF2]−, [BrCl2]−, [IF2]−, [ICl2]−, [IBr2]−, [I2Cl]−, [I2Br]− Bent [ClF2]+, [Cl2F]+, [BrF2]+, [IF2]+, [ICl2]+, [I2Cl]+, [IBr2]+, [I2Br]+, [IBrCl]+ Square planar [ClF4]−, [BrF4]−, [IF4]−, [ICl4]− Disphenoidal (or seesaw) [ClF4]+, [BrF4]+, [IF4]+ Pentagonal planar ‡[IF5]2− Octahedral [ClF6]+, [BrF6]+, [IF6]+, §[ClF6]−, [BrF6]−, [IF6]− Square antiprismatic [IF8]− - ‡ [IF5]2− is one of the two XYn-type species known to have the rare pentagonal planar geometry, the other being [XeF5]−. §[ClF6]− is distorted octahedral as the stereochemical inert pair effect is not significant in the chlorine atom.

The [I3Cl2]+ and [I3Br2]+ ions have a trans-Z-type structure, analogous to that of [I5]+.

%2B_ion.png)

Higher polyiodides

The polyiodide ions have much more complicated structures. Discrete polyiodides usually have a linear sequence of iodine atoms and iodide ions, and are described in terms of association between I2, I− and I−

3 units, which reflects the origin of the polyiodide. In the solid states, the polyiodides can interact with each other to form chains, rings, or even complicated two-dimensional and three-dimensional networks.

Bonding

The bonding in polyhalogen ions mostly invoke the predominant use of p-orbitals. Significant d-orbital participation in the bonding is improbable as much promotional energy will be required, while scant s-orbital participation is expected in iodine-containing species due to the inert pair effect, suggested by data from Mössbauer spectroscopy. However, no bonding model has been capable of reproducing such wide range of bond lengths and angles observed so far.[3]

As expected from the fact that an electron is removed from the antibonding orbital when X2 is ionized to [X2]+, the bond order as well as the bond strength in [X2]+ gets higher, consequently the interatomic distances in the molecular ion is less than those in X2.

Linear or nearly linear triatomic polyhalides have weaker and longer bonds compared with that in the corresponding diatomic interhalogen or halogen, consistent with the additional repulsion between atoms as the halide ion is added to the neutral molecule. Another model involving the use of resonance theory exists, for example, [ICl2]− can be viewed as the resonance hybrid of the following canonical forms:

Evidence supporting this theory comes from the bond lengths (255 pm in [ICl2]− and 232 pm in ICl(g)) and bond stretching wavenumbers (267 and 222 cm−1 for symmetric and asymmetric stretching in [ICl2]− compared with 384 cm−1 in ICl), which suggests a bond order of about 1/2 for each I–Cl bonds in [ICl2]−, consistent with the interpretation using the resonance theory. Other triatomic species [XY2]− can be similarly interpreted.[2]

Synthesis

The formation of polyhalogen ions can be viewed as the self-dissociation of their parent interhalogens or halogens:

- 2 XYn ⇌ [XYn−1]+ + [XYn+1]−

- 3 X2 ⇌ [X3]+ + [X3]−

- 4 X2 ⇌ [X5]+ + [X3]−

- 5 X2 ⇌ 2 [X2]+ + 2 [X3]−

Polyhalogen cations

There are two general strategies for preparing polyhalogen cations:

- By reacting the appropriate interhalogen with a Lewis acid (such as the halides of B, Al, P, As, Sb) either in an inert or oxidizing solvent (such as anhydrous HF) or without one, to give a heteropolyhalogen cation.

- XYn + MYm → [XYn−1]+ + [MYm+1]−

- By an oxidative process, in which the halogen or interhalogen is reacted with an oxidizer and a Lewis acid to give the cation:

- Cl2 + ClF + AsF5 → [Cl3]+[AsF6]−

- In some cases the Lewis acid (the fluoride acceptor) itself acts as an oxidant:

- 3 I2 + 3 SbF5 → 2 [I3]+[SbF6]− + SbF3

Usually the first method is employed for preparing heteropolyhalogen cations, and the second one is applicable to both. The oxidative process is useful in the preparation of the cations [IBr2]+, [ClF6]+, [BrF6]+, as their parent interhalogens, IBr3, ClF7, BrF7 respectively, has never been isolated:

- Br2 + IOSO2F → [IBr2]+[SO3F]−

- 2 ClF5 + 2 PtF6 → [ClF6]+[PtF6]− + [ClF4]+[PtF6]−

- BrF5 + [KrF]+[AsF6]− → [BrF6]+[AsF6]− + Kr

The preparation of some individual species are briefly summarized in the table below with equations:[1][2][3][4]

Synthesis of some polyhalogen cations Species Relevant chemical equation Additional conditions required [Cl2]+ (as [Cl2O2]+) Cl2 + [O2]+[SbF6]− → [Cl2O2]+[SbF6]− in anhydrous HF at low temperatures [Br2]+ Br2 (in BrSO3F) + 3 SbF5 → [Br2]+[Sb3F16]− (not balanced) at room temperature [I2]+ 2 I2 + S2O6F2 → 2 [I2]+[SO3F]− in HSO3F [Cl3]+ Cl2 + ClF + AsF5 → [Cl3]+[AsF6]− at a temperature of 195K(-78oC) [Br3]+ 3 Br2 + 2 [O2]+[AsF6]− → 2 [Br3]+[AsF6]− + 2 O2 [I3]+ 3 I2 + S2O6F2 → 2 [I3]+[SO3F]− [Cl4]+ 2 Cl2 + IrF6 → [Cl4]+[IrF6]− in anhydrous HF, at a temperature below 193 K(-80oC) [I4]2+ 2 I2 + 3 AsF5 → [I4]2+[AsF6−]2 + AsF3 in liquid SO2 [Br5]+ 8 Br2 + 3 [XeF]+[AsF6]− → 3 [Br5]+[AsF6]− + 3 Xe + BrF3 [I5]+ 2 I2 + ICl + AlCl3 → [I5]+[AlCl4]− [I7]+ 7 I2 + S2O6F2 → 2 I7SO3F [ClF2]+ ClF3 + AsF5 → [ClF2]+[AsF6]− [Cl2F]+ 2 ClF + AsF5 → [Cl2F]+[AsF6]− at a temperature below 197 K [BrF2]+ 5 BrF3 + 2 Au → 3 BrF + 2 [BrF2]+[AuF4]− with excess BrF3 required [IF2]+ IF3 + AsF5 → [IF2]+[AsF6]− [ICl2]+ ICl3 + SbCl5 → [ICl2]+[SbCl6]− [IBr2]+ Br2 + IOSO2F → [IBr2]+[SO3F]− [ClF4]+ ClF5 + SbF5 → [ClF4]+[SbF6]− [BrF4]+ BrF5 + AsF5 → [BrF4]+[AsF6]− [IF4]+ IF5 + 2 SbF5 → [IF4]+[Sb2F11]− [ClF6]+ ‡Cs2NiF6 + 5 AsF5 + ClF5 → [ClF6]+[AsF6]− + Ni[AsF6]2 + 2 CsAsF6 [BrF6]+ [KrF]+[AsF6]− + BrF5 → [BrF6]+[AsF6]− + Kr [IF6]+ IF7 + BrF3 → [IF6]+[BrF4]− - ‡ In this reaction, the active oxidizing species is [NiF3]+, which is formed in situ in the Cs2NiF6/AsF5/HF system. It is an even more powerful oxidizing and fluorinating agent than PtF6.

Polyhalogen anions

For polyhalogen anions, there are two general preparation strategies as well:

- By reacting an interhalogen or halogen with a Lewis base, most likely a fluoride:

- [Et4N]+Y− + XYn → [Et4N]+[XYn+1]−

- X2 + X− → X−

3

- By oxidation of simple halides:

- KI + Cl2 → K+[ICl2]−

The preparation of some individual species are briefly summarized in the table below with equations:[1][2][3][4]

Synthesis of some polyhalogen anions Species Relevant chemical equation Additional conditions required [Cl3]−, [Br3]−, [I3]− X2 + X− → [X3]− (X = Cl, Br, I) [Br3]− Br2 + [nBu4N]+Br− → [nBu4N]+[Br3]− in 1,2-dichloroethane or liquid sulfur dioxide. [Br3]− does not exist in solution and is only formed when the salt crystallizes out. [Br5]− 2 Br2 + [nBu4N]+Br− → [nBu4N]+[Br5]− in 1,2-dichloroethane or liquid sulfur dioxide, with excess Br2 [ClF2]− ClF + CsF → Cs+[ClF2]− [BrCl2]−[6]:v1p294 Br2 + Cl2 + 2 CsCl → 2 Cs+[BrCl2]− [ICl2]−[6]:v1p295 KI + Cl2 → K+[ICl2]− [IBr2]−[6]:v1p297 CsI + Br2 → Cs+[IBr2]− [AtBr2]−, [AtICl]−, [AtIBr]−, [AtI2]− AtY + X− → [AtXY]− (X = I, Br, Cl; Y = I, Br) [ClF4]− NOF + ClF3 → [NO]+[ClF4]− [BrF4]− 6 KCl + 8 BrF3 → 6 K+[BrF4]− + 3 Cl2 + Br2 excess BrF5 needed [IF4]− 2 XeF2 + [Me4N]+I− → [Me4N]+[IF4]− + 2 Xe the reactants were mixed at 242 K, then warmed to 298 K for the reaction to proceed [ICl4]−[6]:v1p298 KI + ICl3 → K+[ICl4]− [IF5]2− IF3 + 2 [Me4N]+F− → [Me4N+]2[IF5]2− [IF6]− IF5 + CsF → Cs+[IF6]− [I3Br4]− [PPh4]+Br− + 3 IBr → [PPh4]+[I3Br4]− [IF8]− IF7 + [Me4N]+F− → [Me4N]+[IF8]− in acetonitrile

The higher polyiodides were formed upon crystallization of solutions containing various concentrations of I− and I2. For instance, the monohydrate of KI3 crystallizes when a saturated solution containing appropriate amounts of I2 and KI is cooled.[6]:v1p294

Properties

Stability

In general, a large counter cation or anion (such as Cs+, [SbF6]−) can help stabilize the polyhalogen ions formed in the solid state from lattice energy considerations, as the packing efficiency was increased.

The polyhalogen cations are strong oxidizing agents, as indicated by the fact that they can only be prepared in oxidative liquids as a solvent, such as oleum. The most oxidizing and therefore most unstable ones are the species [X2]+ and [XF6]+ (X = Cl, Br), followed by [X3]+ and [IF6]+.

The stability of the [X2]+ salts (X = Br, I) are thermodynamically quite stable. However, their stability in solution depends on the superacid solvent. For example, [I2]+ is stable in fluoroantimonic acid (HF with 0.2 N SbF5, H0 = −20.65), but disproportionates to [I3]+, [I5]+ and I2 when weaker fluoride acceptors, like NbF5, TaF5 or NaF, are added instead of SbF5.[4]

- 14 [I2]+ + 5 F− → 9 [I3]+ + IF5

For polyhalogen anions with the same cation, the more stable ones are those with a heavier halogen at the center, symmetric ions are also more stable than asymmetric ones. therefore the stability of the anions decrease in the order:

- [I3]− > [IBr2]− > [ICl2]− > [I2Br]− > [Br3]− > [BrCl2]− > [Br2Cl]−

Heteropolyhalogen ions with a coordination number larger than or equal to four can only exist with fluoride ligands.

Color

Most polyhalogen ions are intensely colored, with deepened color as the atomic weight of the constituent element increases. The well-known starch-iodine complex has a deep blue color due to the linear [I5]− ions present in the amylose helix.[4] Some colors of the common species were listed below:[3]

- fluorocations tend to be colorless or pale yellow, other heteropolyhalogen ions are orange, red or deep purple[4]

- compounds of [ICl2]+ are wine red to bright orange; while that of [I2Cl]+ are dark brown to purplish black

- [Cl3]+ is yellow

- [Cl4]+ is blue[2]

- [Br2]+ is cherry red

- [Br3]+ is brown

- [Br5]+ is dark brown

- [I2]+ is bright blue

- [I3]+ is dark brown to black

- [I4]2+ is red to brown

- [I5]+ is green or black, the salt [I5]+[AlCl4]− exists as greenish-black needles, but appears brown-red in thin sections

- [I7]+ is black, if its existence in the compound I7SO3F has been firmly established

- [I15]3+ is black[5]

- [ICl2]− is scarlet red

- [ICl4]− is golden-yellow

- polyiodides have very dark colors, either dark brown or dark blue

Chemical properties

The heteropolyhalogen cations are explosively reactive oxidants, and the cations often have higher reactivity than their parent interhalogens and decompose by reductive pathways. As expected from the highest oxidation state of +7 in [ClF6]+, [BrF6]+ and [IF6]+, these species are extremely strong oxidizing agents, demonstrated by the reactions shown below:

- {{math|2 O2 + 2 [BrF6]+[AsF6]− → 2 [[dioxygenyl|[O2]+]][AsF6]− + 2 BrF5 + F2}}

- Rn + [IF6]+[SbF6]− → [RnF]+[SbF6]− + IF5

Polyhalogen cations with lower oxidation states tend to disproportionate. For example, [Cl2F]+ is unstable in solution and disproportionate completely in HF/SbF5 even at 197K:

- 2 [Cl2F]+ → [ClF2]+ + [Cl3]+

[I2]+ reversibly dimerizes at 193 K, and is observed as the blue color of paramagnetic [I2]+ dramatically shifts to the red-brown color of diamagnetic [I2]+, together with a drop in paramagnetic susceptibility and electrical conductivity when the solution is cooled to below 193 K:[2]

- 2 [I2]+ ⇌ [I4]2+

The dimerization can be attributed to the overlapping of the half-filled π* orbitals in two [I2]+.

[Cl4]+ in [Cl4]+[IrF6]− is structurally analogous to [I4]2+, but decomposes at 195 K to give salts of [Cl3]+ instead of [Cl2]+ and Cl2.[2]

Attempts to prepare ClF7 and BrF7 by fluorinating [ClF6]+ and [BrF6]+ using NOF have met with failure, instead the following reactions occurred:[3]

- [ClF6]+[PtF6]− + NOF → [NO]+[PtF6]− + ClF5 + F2

- [BrF6]+[AsF6]− + 2 NOF → [NO]+[AsF6]− + [NO]+[BrF6]− + F2

The anions are less reactive compared to the cations, and are generally weaker oxidants than their parent interhalogens. They are less reactive towards organic compounds, and some salts are of quite high thermal stability. Salts containing polyhalogen anions of the type M+[XmYnZp]− (where m + n + p = 3, 5, 7, 9...) tend to dissociate into simple monohalide salts between M+ and the most electronegative halogen, so that the monohalide has the highest lattice energy. An interhalogen is usually formed as the other product. The salt [Me4N]+[ClF4]− decomposes at about 100 °C, and salts of [ClF6]− are thermally unstable and can explode even at −31 °C.[4]

References

- King, R. Bruce (2005). "Chlorine, Bromine, Iodine, & Astatine: Inorganic Chemistry". Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Wiley. p. 747. ISBN 9780470862100.

- Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2008). "Chapter 17: The group 17 elements". Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Pearson. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 835. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, Geoffrey; Murillo, Carlos A.; Bochmann, Manfred (1999). Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0471199571.

- Wiberg, Egon; Wiberg, Nils; Holleman, Arnold Frederick (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Academic Press. pp. 419–420. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- Brauer, G., ed. (1963). Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). New York: Academic Press.

-.png)