Polyabolo

In recreational mathematics, a polyabolo (also known as a polytan) is a shape formed by gluing isosceles right triangles edge-to-edge, making a polyform with the isosceles right triangle as the base form. Polyaboloes were introduced by Martin Gardner in his June 1967 "Mathematical Games column" in Scientific American.[1]

Nomenclature

The name polyabolo is a back formation from the juggling object 'diabolo', although the shape formed by joining two triangles at just one vertex is not a proper polyabolo. By false analogy, treating the di- in diabolo as meaning "two", polyaboloes with from 1 to 10 cells are called respectively monaboloes, diaboloes, triaboloes, tetraboloes, pentaboloes, hexaboloes, heptaboloes, octaboloes, enneaboloes, and decaboloes. The name polytan is derived from Henri Picciotto's name tetratan and alludes to the ancient Chinese amusement of tangrams.

Combinatorial enumeration

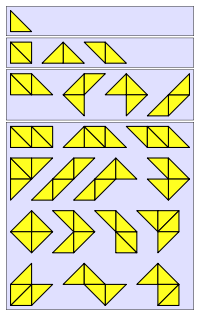

There are two ways in which a square in a polyabolo can consist of two isosceles right triangles, but polyaboloes are considered equivalent if they have the same boundaries. The number of nonequivalent polyaboloes composed of 1, 2, 3, … triangles is 1, 3, 4, 14, 30, 107, 318, 1116, 3743, … (sequence A006074 in the OEIS).

Polyaboloes that are confined strictly to the plane and cannot be turned over may be termed one-sided. The number of one-sided polyaboloes composed of 1, 2, 3, … triangles is 1, 4, 6, 22, 56, 198, 624, 2182, 7448, … (sequence A151519 in the OEIS).

As for a polyomino, a polyabolo that can be neither turned over nor rotated may be termed fixed. A polyabolo with no symmetries (rotation or reflection) corresponds to 8 distinct fixed polyaboloes.

A non-simply connected polyabolo is one that has one or more holes in it. The smallest value of n for which an n-abolo is non-simply connected is 7.

Tiling rectangles with copies of a single polyabolo

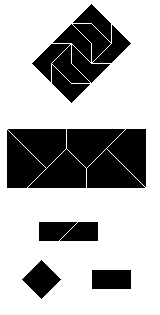

In 1968, David A. Klarner defined the order of a polyomino. Similarly, the order of a polyabolo P can be defined as the minimum number of congruent copies of P that can be assembled (allowing translation, rotation, and reflection) to form a rectangle.

A polyabolo has order 1 if and only if it is itself a rectangle. Polyaboloes of order 2 are also easily recognisable. Solomon W. Golomb found polyaboloes, including a triabolo, of order 8.[2] Michael Reid found a heptabolo of order 6.[3] Higher orders are possible.

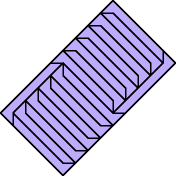

There are interesting tessellations of the Euclidean plane involving polyaboloes. One such is the tetrakis square tiling, a monohedral tessellation that fills the entire Euclidean plane with 45–45–90 triangles.

References

- Gardner, Martin (June 1967). "The polyhex and the polyabolo, polygonal jigsaw puzzle pieces". Scientific American. 216 (6): 124–132.

- Golomb, Solomon W. (1994). Polyominoes (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 101. ISBN 0-691-02444-8.

- Goodman, Jacob E.; O'Rourke, Joseph, eds. (2004). Handbook of Discrete and Computational Geometry (2nd ed.). Chapman & Hall/CRC. p. 349. ISBN 1-58488-301-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polyabolo. |