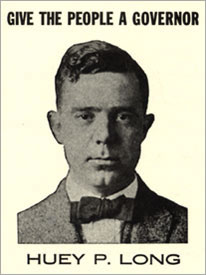

Political views of Huey Long

The political views of Huey P. Long have presented historians and biographers with some difficulty.[1] While most say that Senator Huey Long was a populist, little else can be agreed on. Huey Long's opponents, both during his life and after, often drew connections between him and his ideology and far-left and right political movements, comparing it to everything from European Fascism, Stalinism, and later McCarthyism. When asked about his own philosophy, Long simply replied: "Oh, hell, say that I’m sui generis and let it go at that."

Authoritarianism

Long expressed interest in authoritarianism; he was reportedly gripped by the idea that he was the reincarnated ego of Napoleon Bonaparte.[2]

Communism

During his lifetime, Long's political philosophy, particularly his Share Our Wealth program, was strongly criticized by more conservative politicians. They feared that such a scheme was decidedly communist. The former Louisiana governor Ruffin G. Pleasant, for instance, decried Long as "the 'ultra Socialist' whose views outreached 'Marx, Lenin, and Trotsky.'"[3] Similarly, in 1935, the New York American accused Long's Share the Wealth program of being "molded in the criminal brains of the leader of the Paris Commune and sanctified in the brains of an oriental fanatic, Nicolai Lenin."[4] He was jokingly labelled the "Karl Marx of the Hillbillies".[5] Deflecting such attacks, Long occasionally painted Roosevelt as a communist, once suggesting that Roosevelt "hold the Democratic convention and Communist convention together and save money."[6]

Despite claims from right-wing opponents, Long's program diverged significantly from Marxist communism. In particular, the Share Our Wealth program preserved the concept of private property and also sought to avoid any need for violent revolution.[7] When asked whether his plan was communist, Long replied: "Communism? Hell no! ... This plan is the only defense this country's got against communism."[8] Long also called his program "the only stop-gap to Communism!"[9]

Although conservatives labeled Long as a communist, legitimate American communists sought to distance themselves from Long and his Share Our Wealth program. They believed his policies both preserved the capitalist enterprise and diverted interest away from their own party. Some of Long's fiercest critics were prominent American communists, such as Sender Garlin and Alexander Bittelman.[7] They argued that Long's populist rhetoric and antics belied a decidedly anti-labor philosophy; Garlin, for instance, noted that while Long constructed thousands of miles of roads and numerous bridges, the state paid its workers only 30 cents an hour—10 cents less than what the National Recovery Administration called for during the Great Depression.[10]

Fascism

With the rise of fascism in 1930s Europe, many noted parallels to Long. U.S. General Hugh Johnson described Long as "the Hitler of one of our sovereign states." American fascist Lawrence Dennis described Long as "the nearest approach to a national fascist leader" in the United States.[11] Journalist Raymond Gram Swing claimed that Long wished to "Hitlerize America". In an effort to distance Long from communism, many socialists, such as Norman Thomas, also sought to smear Long as a fascist. Communist writer Sender Garlin labelled him the "personification of the fascist menace in the United States," and noted that his swinging arm gestures were similar to those of Hitler.[12] Newspaper Daily Worker ran headlines such as "Huey Long - Louisiana's 'Hitler' Is Sole Lawmaker".[13] Even Long's brother Julius claimed that he was "trying to be a Hitler."[14]

Although often denounced as a fascist, Long was not anti-Semitic, nor any more anti-Communist than most politicians at the time. When asked about common comparisons between him and Adolf Hitler, Long replied "Don't compare with that so-and-so. Anybody that lets his public policies be mixed up with religious prejudice is a plain God-damned fool." and later commented "I don't know much about Hitler. Except that last thing, about the Jews. There has never been a country that put its heel down on the Jews that ever lived afterwards."[15] Several of Long's political and personal friends were Jews, such as Abraham Shushan and Seymour Weiss. Additionally, Long's hostile attitude to corporations was not compatible with fascism. Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. noted that "Long's political fantasies had no tensions, no conflicts, except of the most banal kind, no heroism or sacrifice, no compelling myths of class or race or nation."[16]

Life Magazine said "The late Huey P. Long, who knew all the tricks of the dissembling demagogue, was once asked: “Do you think we will ever have Fascism in America?” Said the Kingfish: “Sure, only we’ll call it anti-Fascism.” [17] Several other similar quotes have been credited to Long, but many challenge the validity of these quotes.[18][19] George Sokolsky remembered having asked Long if he was a fascist. “Fine,” Long told him in a conversation that took place less than a year before he was killed. “I’m Mussolini and Hitler rolled into one. Mussolini [force-fed dissidents] castor oil; I’ll give them Tabasco, and then they’ll like Louisiana.” Then he laughed."[20]

Race

For much of the 20th century, most historians considered Long to be an egalitarian in terms of race; Long historian T. Harry Williams, for instance, wrote that Long was "the first Southern mass leader to leave aside race baiting and appeals to the Southern tradition and the Southern past and address himself to the social and economic problems of the present."[21] When asked how he would treat blacks if he were to become President, Long responded, "Treat them just the same as anybody else, give them an opportunity to make a living, and to get an education."[22] Unlike many other southern demagogues, Long resisted associating himself with the Ku Klux Klan. When KKK Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans announced plans to campaign against Long in 1934, Long declared "that Imperial bastard will never set foot in Louisiana," threatening that Evans would leave the state with "his toes turned up." Many historians also argue that Long's building projects and social reforms helped all of the lower classes in Louisiana, regardless of race.[21]

However, historian Glen Jeansonne argued that Long was "more racist, less unbiased, less principled, and less different from other Louisiana politicians of his time than the [historical] literature implies."[23] Long had never faced a serious election that hinged on questions of race or racism. This was largely because after the Louisiana Constitution of 1898, which virtually disenfranchised blacks by raising barriers to voter registration, was ratified "race was an irrelevant political issue" and black Louisianians "were segregated, ghettoized, ignored."[23][24] Long never had to address the subject of race in politics.[23] Jeansonne also points out that if Long intended to help black Louisianians with his social program, it seems likely that he would have attempted to engage and enfranchise more black voters so as to secure their political support. This, however, was not the case. During Long's tenure as governor, the number of registered black voters declined.[24] In a 1935 interview, Long explained "A lot of guys would have been politically murdered for what I've been able to do quietly for the niggers. But do you think I could get away with niggers voting? No siree!" Long also declined to support federal anti-lynching legislation: "Can't do the dead nigra no good."[25]

Nevertheless, many of Long's efforts did benefit the black community. Long's programs, instituted when he was governor and senator, allowed a number of black Louisianans to receive an education, file for tax exemptions, and also vote without having to worry about poll taxes. A number of black ministers organized Share Our Wealth club chapters.[26] When black leaders in New Orleans protested that the staff at one of his recently constructed hospitals was entirely white, Long quickly made several positions open to black nurses. In a 1935 interview with black activist Roy Wilkins, Long touted his new egalitarian school system: "My educational system is for blacks and whites."[27] Trying to strike a balance among differing interpretations of Long's racial views, Wilkins later wrote, "My guess is that Huey ... wouldn't hesitate to throw Negroes to the wolves if it became necessary; neither would he hesitate to carry them along if the good they did him was greater than the harm."[28] After Long's death, the official journal of the NAACP, The Crisis, wrote "Of the late Senator Huey P. Long, Negro Americans may say that he was the only Southern politician in recent decades to achieve the national spotlight without the use of racial and color hatred as campaign material... But when this is said, so far as Negroes are concerned, is done."[29]

References

- Haas (1994), p. 125.

- Harris (1938), p. 40

- Haas (1991), p. 29.

- Haas (1991), pp. 29–30.

- Kane, Harnett Thomas (January 31, 1971). Huey Long's Louisiana Hayride. Pelican. p. 62. ISBN 978-0882896182.

- Jeansonne, Glen (Autumn 1980). "Challenge to the New Deal: Huey P. Long and the Redistribution of National Wealth". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 21 (4): 337. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Haas (1991), p. 30.

- Walsh, David (November 8, 2006). "All the King's Men and Man of the Year: Simply Unserious". World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Haas (1991), p. 31.

- Haas (1991), p. 33.

- Haas, Edward F. (Spring 2006). "Huey Long and the Dictators". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 47 (2): 133. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Haas, Edward F. (Spring 2006). "Huey Long and the Dictators". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 47 (2): 134. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Haas, Edward F. (Spring 2006). "Huey Long and the Dictators". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 47 (2): 134–35. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Haas, Edward F. (Spring 2006). "Huey Long and the Dictators". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 47 (2): 135. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Williams (1981) [1969], p. 761.

- Leuchtenburg, William E. (Fall 1985). "FDR And The Kingfish". American Heritage. Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- "Some of the Voices of Hate". Life Magazine.

- George, John H.; Boller, Paul F. (June 14, 1990). They Never Said It. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0195064698.

- Evon, Dan (August 7, 2018). "Did Winston Churchill Say 'The Fascists of the Future Will Call Themselves Anti-Fascists?'". Snopes. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Neklason, Annika (March 3, 2019). "When Demagogic Populism Swings Left". The Atlantic. New York City. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Jeansonne (1992), p. 265.

- Williams (1981) [1969], p. 704.

- Jeansonne (1992), p. 266.

- Jeansonne (1992), p. 271.

- Brinkley (2011) [1983], p. 33.

- Jeansonne (1992), p. 275.

- Brinkley (2011) [1983], p. 32.

- Jeansonne (1992), p. 281.

- Brinkley (2011) [1983], p. 34.

Bibliography

- Brinkley, Alan (2011) [1982]. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, and the Great Depression. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307803221.

- Haas, Edward F. (1991). "Huey Long and the Communists". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 32 (1): 29–46. JSTOR 4232863. (subscription required)

- Haas, Edward F. (February 1994). "Huey Pierce Long and Historical Speculation". The History Teacher. 27 (2): 271–73. JSTOR 4231135.

- Jeansonne, Glen (1992). "Huey Long and Racism". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 22 (3): 265–82. JSTOR 423295. (subscription required)

- Williams, T. Harry (1981) [1969]. Huey Long. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0394747903.