Plum-headed parakeet

The plum-headed parakeet (Psittacula cyanocephala) is a parakeet in the family Psittacidae. It is endemic to the Indian Subcontinent and was once thought to be conspecific with the blossom-headed parakeet (Psittacula roseata) but was later elevated to a full species. Plum-headed parakeets are found in flocks, the males having a pinkish purple head and the females, a grey head. They fly swiftly with twists and turns accompanied by their distinctive calls.

| Plum-headed parakeet | |

|---|---|

_Photograph_By_Shantanu_Kuveskar.jpg) | |

| A male and female | |

| Calls | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittaculidae |

| Genus: | Psittacula |

| Species: | P. cyanocephala |

| Binomial name | |

| Psittacula cyanocephala (Linnaeus, 1766) | |

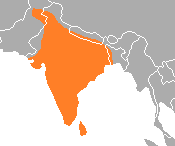

| |

| Distribution range of plum-headed parakeet | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Psittacus cyanocephalus Linnaeus, 1766 | |

Taxonomy

In 1760 the French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson included a description of the plum-headed parakeet in his Ornithologie based on a specimen collected in India. He used the French name Le perruche a teste bleu and the Latin name Psittaca cyanocephalos.[2] Although Brisson coined Latin names, these do not conform to the binomial system and are not recognised by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.[3] When in 1766 the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus updated his Systema Naturae for the twelfth edition he added 240 species that had been previously described by Brisson.[3] One of these was the plum-headed parakeet. Linnaeus included a terse description, coined the binomial name Psittacus cyanocephalus and cited Brisson's work.[4] The specific name cyanocephalus/cyanocephala combines the Ancient Greek words kuanos "dark-blue" and -kephalos "-headed".[5] This species is now placed in the genus Psittacula which was introduced by the French naturalist Georges Cuvier in 1800.[6]

_in_Kawal_WS%2C_AP_W_IMG_1590.jpg)

Description

The plum-headed parakeet is a mainly green parrot, 33 cm long with a tail up to 22 cm. The male has a red head which shades to purple-blue on the back of the crown, nape and cheeks while the female has blueish-gray head. There is a narrow black neck collar with verdigris below on the nape and a black chin stripe that extends from the lower mandible. There is a red shoulder patch and the rump and tail are bluish-green, the latter tipped white. The upper mandible is orangish-yellow, and the lower mandible is dark. The female has a dull bluish grey head and lacks the black and verdigris collar which is replaced by yellow. The upper-mandible is corn-yellow and there is no black chin stripe or red shoulder patch. Immature birds have a green head and both mandibles are yellowish. The dark head is acquired after a year.[7][8][9] The delicate bluish red appearance resembling the bloom of a peach is produced by a combination of blue from the optical effects produced by the rami of the feather and a red pigment in the barbules.[10]

Some authors have considered the species to have two subspecies, the nominate from peninsular India (type locality restricted to Gingee[11]) and the population from the foothills of the Himalayas as bengalensis on the basis of the colour of the head in the male which is more red and less blue.[9] Newer works consider the species to be monotypic.[7]

The different head colour and the white tip to the tail distinguish this species from the similar blossom-headed parakeet (Psittacula roseata). The shoulder patch is maroon coloured and the shorter tail is tipped yellow in P. roseata.[7]

A supposed species of parakeet, the so-called intermediate parakeet Psittacula intermedia is thought to be a hybrid of this and the slaty-headed parakeet (Psittacula himalayana).[12]

Habitat and distribution

The plum-headed parakeet is a bird of forest and open woodland, even in city gardens. They are found from the foothills of the Himalayas south to Sri Lanka. They are not found in the dry regions of western India.[9] They are sometimes kept as pets and escaped birds have been noted in New York,[13] Florida[14] and in some places in the Middle East.[15]

Behaviour and ecology

The plum-headed parakeet is a gregarious and noisy species with range of raucous calls. The usual flight and contact call is tuink? repeated now and then. The flight is swift and the bird often twists and turns rapidly. It makes local movements, driven mainly by the availability of the fruit and blossoms which make up its diet. They feed on grains, fruits, the fleshy petals of flowers (Salmalia, Butea) and sometimes raid agricultural fields and orchards. The breeding season in India is mainly from December to April and July to August in Sri Lanka. Courtship includes bill rubbing and courtship feeding.[16] It nests in holes, chiselled out by the pair, in tree trunks, and lays 4–6 white eggs. The female appears to be solely responsible for incubation and feeding. They roost communally. In captivity it can learn to mimic beeps and short whistling tunes, and can talk very well.[9]

Neoaulobia psittaculae, a quill mite, has been described from the species.[17] A species of Haemoproteus, H. handai, has been described from blood samples from the plum-headed parakeet.[18]

History

_-upper_body_of_pet.jpg)

Ctesias of Cnidus, a 5th-century BC Greek physician to the emperor Artaxerxes II, who ruled the Achaemenid Empire, accompanied Artaxerxes on his 401 BC campaign against his brother Cyrus the Younger. He was author of the lost Indica, a description of India which he wrote based on his experience in Persia and information he gathered from Persian accounts.[19] Fragments of the Indica were preserved by Photius of Constantinople in his Bibliotheca in the 9th century AD; one of these has been identified as describing Psittacula cyanocephala and its abilities as a talking bird.[20] It is likely Ctesias saw the bird himself, with an Indian handler; though his description could also apply to Psittacula roseata, that species is native to areas far further east and is much less likely candidate in Greater Iran.[20][21] In his summary of Ctesias, Photius wrote:[20][21]

[Ctesias says] there is a bird called the bittakos which has a human voice, is capable of speech, and grows to the size of a falcon. It has a crimson face and a black beard and is dark blue as far as the neck … like cinnabar. It can converse like a human in Indian but if taught Greek, it can also speak Greek. |

καὶ περὶ τοῦ ὀρνέου τοῦ βυττάκου, ὅτι γλῶσσαν ἀνθρωπίνην ἔχει καὶ φωνήν, μέγεθος μὲν ὅσον ἱέραξ, πορφύρεον δὲ πρόσωπον, καὶ πώγωνα φέρει μέλανα. Αὐτὸ δὲ κυάνεόν ἐστιν ὡς τὸν τράχηλον ὥσπερ κιννάβαρι. Διαλέγεσθαι δὲ αὐτὸ ὥσπερ ἄνθρωπον ἰνδιστί, ἂν δὲ ἑλληνιστὶ μάθῃ, καὶ ἑλληνιστί. |

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Psittacula cyanocephala". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en ordres, sections, genres, especes & leurs variétés (in French and Latin). Volume 4. Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. pp. 359–362, Plate 19 fig 2. The two stars (**) at the start of the section indicates that Brisson based his description on the examination of a specimen.

- Allen, J.A. (1910). "Collation of Brisson's genera of birds with those of Linnaeus". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 28: 317–335.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1766). Systema naturae : per regna tria natura, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1, Part 1 (12th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 141.

- Jobling, J.A. (2018). del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.; Christie, D.A.; de Juana, E. (eds.). "Key to Scientific Names in Ornithology". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- Cuvier, Georges (1800). Leçons d'Anatomie Comparée (in French). Volume 1. Paris: Baudouin. Table near end.

- Rasmussen PC & JC Anderton (2005). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Washington DC and Barcelona: Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. pp. 219–220.

- Blanford WT (1895). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Birds. Volume 3. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 251–252.

- Ali, Sálim; Ripley, S. Dillon (1981) [1969]. Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan: together with those of Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, and Sri Lanka - Volume 3: Stone Curlews to Owls. Bombay Natural History Society (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 178–181. ISBN 0-19-563695-3. OCLC 41224182.

- Chandler, Asa C. (1916). "A study of the structure of feathers, with reference to their taxonomic significance". University of California Publications in Zoology. 13 (1): 243–446 [278].

- Whistler, Hugh & NB Kinnear (1935). "The Vernay Scientific Survey of the Eastern Ghats (Ornithological Section)". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 37 (4): 751–763.

- Rasmussen, P. C. & N. J. Collar (1999). "On the hybrid status of Rothschilds's Parakeet Psittacula intermedia (Aves, Psittacidae)" (PDF). Bull. Br. Mus. (Nat. Hist.) Zool. 65: 31–50.

- Bull, John (1973). "Exotic Birds in the New York City Area". The Wilson Bulletin. 85 (4): 501–505.

- Pranty, Bill and Susan Epps (2002). "Distribution, population status, and documentation of exotic parrots in Broward County, Florida" (PDF). Florida Field Naturalist. 30 (4): 111–131. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-26. Retrieved 2012-03-27.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Porter, R Simon Aspinall (2010). Birds of the Middle East. A&C Black. p. 10.

- Tiwari, NK (1930). "The mating of the Blossom-headed Paroquet (Psittacula cyanocephala)". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 34 (1): 254–255.

- Fain, A.; Bochkov, A.; Mironov, S. (2000). "New genera and species of quill mites of the family Syringophilidae (Acari: Prostigmata)". Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Entomologie. 70: 33–70.

- Bennett, GF; M. A. Peirce (1986). "Avian Haemoproteidae. 21. The haemoproteids of the parrot family Psittacidae". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 64 (3): 771–773. doi:10.1139/z86-114.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Nichols, Andrew (2011). Ctesias: on India and fragments of his minor works. London: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 1-4725-1997-3. OCLC 859581997.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Bigwood, J. M. (1993). "Ctesias' Parrot". The Classical Quarterly. 43 (1): 321–327. doi:10.1017/S0009838800044396. ISSN 0009-8388.

- Nichols, Andrew (2008). "The Complete Fragments of Ctesias of Cnidus". University of Florida. PhD thesis. pp. 211, 203. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Psittacula_cyanocephala. |