Pleurobranchus areolatus

Pleurobranchus areolatus is a species of pleurobranchid sea slug, a type of marine gastropod mollusc, commonly found in the Caribbean Sea. It is up to 15 cm long and it feeds on ascidians.

| Pleurobranchus areolatus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dorsal view | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. areolatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Pleurobranchus areolatus | |

| Synonyms[2][3] | |

|

Pleurobranchus crossei Vayssière, 1896[4] | |

Taxonomy

Although there were believed to occur six species of Pleurobranchus in the Caribbean Sea, the other five (P. atlanticus Abbott, 1949, P. evelinae Thompson, 1977, P. crossei Vayssière, 1896, Susania gardineri White, 1952, P. reesi White, 1952 and P. emys Ev. Marcus, 1984) were synonymized with P. areolatus in 2015, based on molecular and morphological evidence.[2][3] The specific names P. areolatus and P. evelinae were also commonly in use in literature, while other names were not.[2]

There is no known type material of Pleurobranchus areolatus, Susania gardineri and P. reesi, but the anatomy of Mörch's type specimen was illustrated by Rudolph Bergh in 1897.[2][9] Type material of P. atlanticus is stored at the National Museum of Natural History (Smithsonian Institution), the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University and the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Those of P. crossei and P. evelinae are at the National Museum of Natural History (France) and the Natural History Museum, London, respectively.[2]

The sister species (the closest relative) is Pleurobranchus varians from the Central Pacific.[2] Those two species split 3.10 million years ago (the Isthmus of Panama formed 3.1–3.4 Mya).[2] Both species have color morphs and for their proper determination the knowledge of their locality is needed.[2]

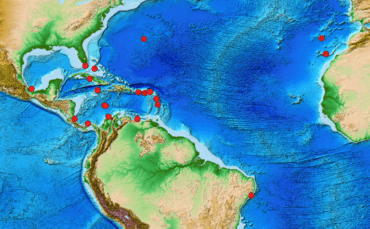

Distribution

Pleurobranchus areolatus occurs off Mexico, Costa Rica, Venezuela, Brazil, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, St. Thomas, Aruba, St. Maarten/St Martin, Bahamas, Bermuda, Panama,[3] Canary Islands and Madeira.[10] This was the only species of Pleurobranchus considered to occur in the Caribbean Sea[2] until 2016, when Pleurobranchus iouspi was reported from Santa Marta, Colombia.[10] The type locality is Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands.[1]

P. areolatus was also reported from the eastern Pacific, but those records were identified as Pleurobranchus digueti in 2015.[2]

Description

The shape of the body is oval. The dorsum contains numerous small, polygonal and flat tubercles.[3] The background color ranges from light brown to deep violet, with varying degrees of opaque white pigment on the tubercles.[3] In some cases the opaque white pigment is arranged in a symmetrical pattern across the body.[3] It is up to 150 mm long.[3]

Rhinophores are rolled and fused at the base, with horizontal striations from base to tip.[3] The color pattern of rhinophores is the same as color pattern of the body.[10]

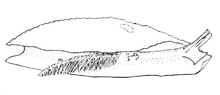

Left side view. |

.jpg) Left side view. |

A well marked pedal gland is visible at the posterior end of the foot in some preserved specimens.[5][2]

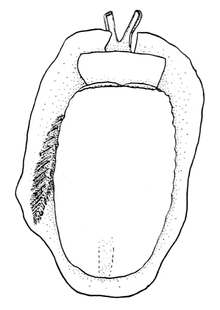

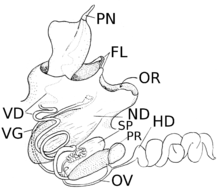

Drawing of right side view showing the position of the internal shell, the gill, anus behind the gill, and genital pore in front of the gill. |

Drawing ventral view shows rhinophores, anterior sinus, velum, foot, gill and posterior pedal gland. |

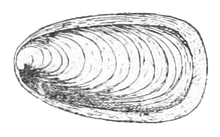

The shell is reduced and internal (as in all other Pleurobranchus species).[3][2] The shell itself does not allow proper species identification within the genus Pleurobranchus.[2] The shape of the shell is oval.[2] The protoconch has one whorl and the size of the protoconch is about 400 μm.[2]

Drawing of dorsal view of the internal shell. |

Drawing of ventral view of the internal shell including the hyaline sheath. |

The most recent drawing of the reproductive system was published by Goodheart et al. (2015)[2] and by Alvim & Pimenta (2016).[10] The genital cup is just before the gill on the right side of the body.[5] The reproductive system is triaulic (it has two female openings and one male opening).[2] The shape of the prostate is elongated and the frontal part of the prostate is rounded.[10]

The radula has 73 rows, it has no central tooth and it has 115 lateral teeth on both sides (radular formula 73 × 115.0.115),[2] while the radular formula reported from smaller specimens (27 mm) is 66 × 90.0.90.[10]

The gill has the size of 2/3 of the body in living specimens of 27 mm in length.[10] The circulatory system was described by Alvim & Pimenta in detail in 2016, but it is the same as in Pleurobranchus reticulatus.[10] They also described the nervous system, which is very similar to that of P. reticulatus.[10]

Ecology

Pleurobranchus areolatus was found to be abundant in Biscayne Bay, Florida in 1946.[5] Minimum recorded depth is 0 m.[11] Maximum recorded depth is 70 m.[11] This species is found under rocks and coral rubble.[3] For example in Florida it is sometimes found among Porites porites corals.[5]

They are laying large, translucent and gelatinous egg masses during spring in Florida.[5]

All species in the genus Pleurobranchus are carnivorous.[2] P. areolatus probably feeds on ascidians,[3] for example, Didemnum sp.[12]

Its ectoparasites include copepod Anthessius ovalipes.[13]

Rodriguesic acids and its esters (they are modified diketopiperazines) were isolated from P. areolatus in 2014.[12] These are the first diketopiperazine derivatives isolated from a mollusc.[12] Similar diketopiperazines were isolated also from ascidians Didemnum sp.[12] These derivatives may either result from a P. areolatus symbiont or may come from feeding on the ascidian.[12] These chemical compounds may be used by P. areolatus as a chemical defense.[12]

References

This article incorporates Creative Commons (CC-BY-4.0) text from the reference[3] and public domain text from the reference[5]

- Mörch O. A. (1863). "Contributions la faune malacologique des Antilles danoises". Journal de Conchyliologie 11: 21–43. pages 28–29 (in French).

- Goodheart J., Camacho-García Y., Padula V., Schrödl M., Cervera J. L., Gosliner T. M. & Valdés Á. (2015). "Systematics and biogeography of Pleurobranchus Cuvier, 1804, sea slugs (Heterobranchia: Nudipleura: Pleurobranchidae)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 174(2): 322–362. doi:10.1111/zoj.12237.

- Goodheart J. A., Ellingson R. A., Vital X. G., Galvão Filho H. C., McCarthy J. B., Medrano S. M., Bhave V. J., García-Méndez K., Jiménez L. M., López G. & Hoover C. A. (2016). "Identification guide to the heterobranch sea slugs (Mollusca: Gastropoda) from Bocas del Toro, Panama". Marine Biodiversity Records 9(1), p.56. doi:10.1186/s41200-016-0048-z

- Vayssière A. (1896). "Description de deux especes nouvelles de Pleurobranchides". Journal de Conchyliologie 44: 353–356, fig. 1.

- Abbott R. T. (1949). "A new Florida species of the tectibranch genus Pleurobranchus". The Nautilus 62: 73–78, plate 5, figs 1–10.

- White K. M. (1952). "On a collection of molluscs from Dry Tortugas, Florida". Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London 29(2–3): 106–120. pages 106–107, plate 6, figures 1–2.

- Thompson T. E. (1977). "Jamaican opisthobranch molluscs I". Journal of Molluscan Studies 43(2): 93–140. pages 108–110, figs 12E, F, 13C–E.

- Marcus E. (1984). "The western Atlantic warm water Notaspidea (Gastropoda, Opisthobranchia), Part 2". Boletim de Zoologia, Universidade São Paulo 8: 43–76. page 70, figs 62–66.

- (in German) Bergh L. S. R. (1897). "Malacologische Untersuchungen. Band 7, Heft 1–2 (Die Pleurobranchiden)". In: Semper C. (ed.), Reisen im Archipel der Philippinen, 1–115. pls. 1–8. Pages 111–113, plate 9, figs 31–41.

- Alvim J. & Pimenta A. D. (2016). "Comparative Morphology and Redescription of Pleurobranchus Species (Gastropoda, Pleurobranchoidea) from Brazil". Zoological Studies 55(15): doi:10.6620/ZS.2016.55-15.

- Welch J. J. (2010). "The “Island Rule” and Deep-Sea Gastropods: Re-Examining the Evidence". PLoS ONE 5(1): e8776. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0008776.

- Pereira F. R., Santos M. F., Williams D. E., Andersen R. J., Padula V., Ferreira A. G. & Berlinck R. G. (2014). "Rodriguesic acids, modified diketopiperazines from the gastropod mollusc Pleurobranchus areolatus". Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society 25(4): 788–794. doi:10.5935/0103-5053.20140037.

- Walter T. Chad (2015). Anthessius ovalipes Stock, Humes & Gooding, 1963. In: Walter, T.C. & Boxshall, G. (2015). World of Copepods database. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=348850 on 2016-10-15