Planigon

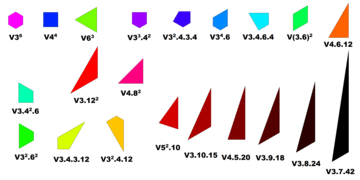

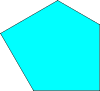

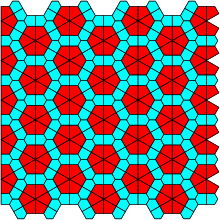

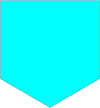

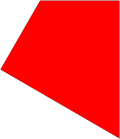

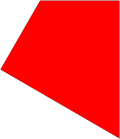

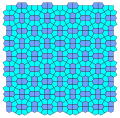

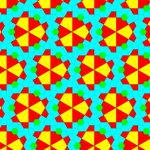

In geometry, a planigon is a convex polygon that can fill the plane with only copies of itself (which are isotopic to the fundamental units of monohedral tessellations). In the Euclidean plane there are 3 regular forms equilateral triangle, squares, and regular hexagons; and 8 semiregular forms; and 4-demiregular forms which can tile the plane with other planigons.

All angles of a planigon are whole divisors of 360°. Tilings are made by edge-to-edge connections by perpendicular bisectors of the edges of the original uniform lattice, or centroids along common edges (they coincide).

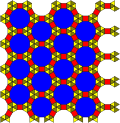

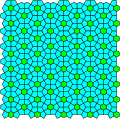

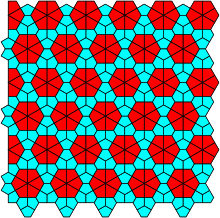

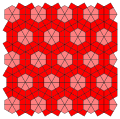

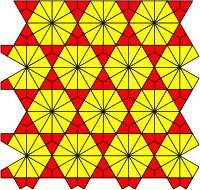

Tilings made from planigons can be seen as dual tilings to the regular, semiregular, and demiregular tilings of the plane by regular polygons.

History

In the 1987 book, Tilings and Patterns, Branko Grünbaum calls the vertex-uniform tilings Archimedean in parallel to the Archimedean solids. Their dual tilings are called Laves tilings in honor of crystallographer Fritz Laves.[1][2] They're also called Shubnikov–Laves tilings after Shubnikov, Alekseĭ Vasilʹevich.[3] John Conway calls the uniform duals Catalan tilings, in parallel to the Catalan solid polyhedra.

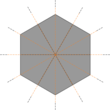

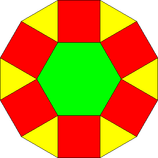

The Laves tilings have vertices at the centers of the regular polygons, and edges connecting centers of regular polygons that share an edge. The tiles of the Laves tilings are called planigons. This includes the 3 regular tiles (triangle, square and hexagon) and 8 irregular ones.[4] Each vertex has edges evenly spaced around it. Three dimensional analogues of the planigons are called stereohedrons.

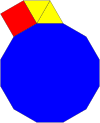

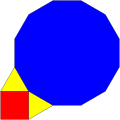

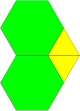

These tilings are listed by their face configuration, the number of faces at each vertex of a face. For example V4.8.8 (or V4.82) means isosceles triangle tiles with one corner with four triangles, and two corners containing eight triangles.

Construction

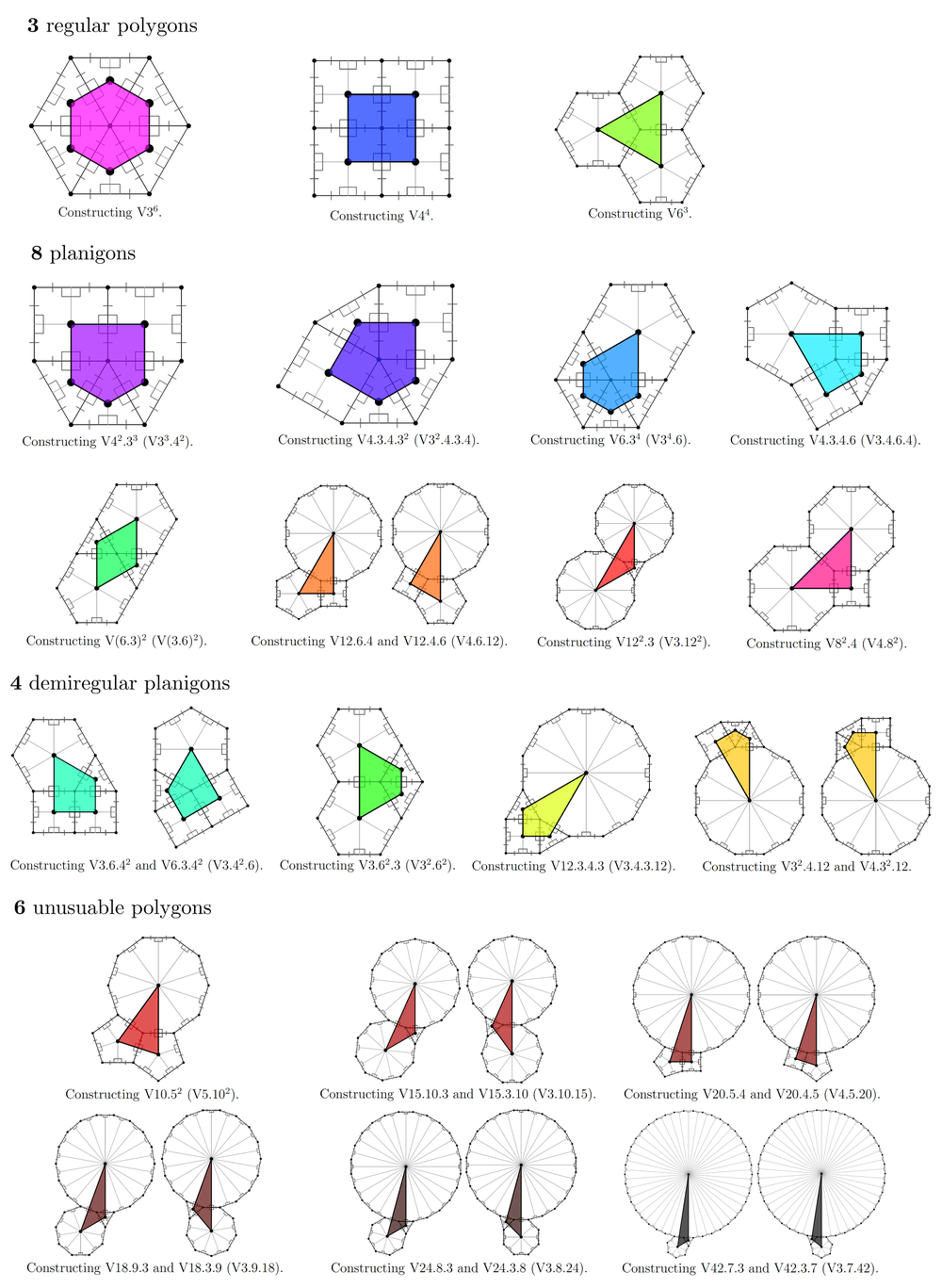

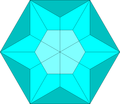

The Conway operation of dual interchanges faces and vertices. In Archimedean solids and k-uniform tilings alike, the new vertex coincides with the center of each regular face, or the centroid. In the Euclidean (plane) case; in order to make new faces around each original vertex, the centroids must be connected by new edges, each of which must intersect exactly one of the original edges. Since regular polygons have dihedral symmetry, we see that these new centroid-centroid edges must be perpendicular bisectors of the common original edges (e.g. the centroid lies on all edge perpendicular bisectors of a regular polygon). Thus, the edges of k-dual uniform tilings coincide with centroid-edge midpoint line segments of all regular polygons in the k-uniform tilings.

So, we can alternatively construct k-dual uniform tilings (and all 21 planigons) equivalently by forming new centroid-edge midpoint line segments of the original regular polygons (dissecting the regular n-gons into n congruent deltoids, ortho), and then removing the original edges (dual). Closed planigons will form around interior vertices, and line segments of (many possible) planigons will form around boundary vertices, giving a faithful k-dual uniform lattice (ortho-superimposable and to scale). On the other hand, centroid-centroid connecting only yields interior planigons (with variable translation and scale), but this construction is nonetheless equivalent in the interior. If the original k-uniform tiling fills the entire frame, then so will the k-dual uniform lattice by the first construction, and the boundary line segments can be ignored (equivalent to second construction).

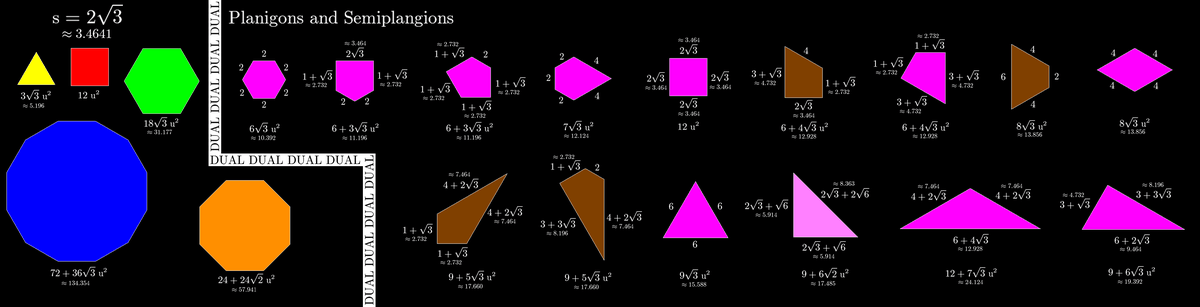

As seen below, some types of vertex polygons are different from their mirror images and are listed twice. For example, a triangle are mirror images if are all unique. In these images, the vertex polygons are listed counter clockwise from the right, and shaded in various colors with wavelength frequency inverse to area. Note, the 4.82 violet-red planigon is colored out-of-place since it cannot exist with any other planigon in any k-uniform tiling. There are 29 possible regular vertex polygons (21 excluding enantiomorphs): 3 regular polygons, 8 planigons, 4 demiregular planigons, and 6 unusable polygons.

An Alternate Construction

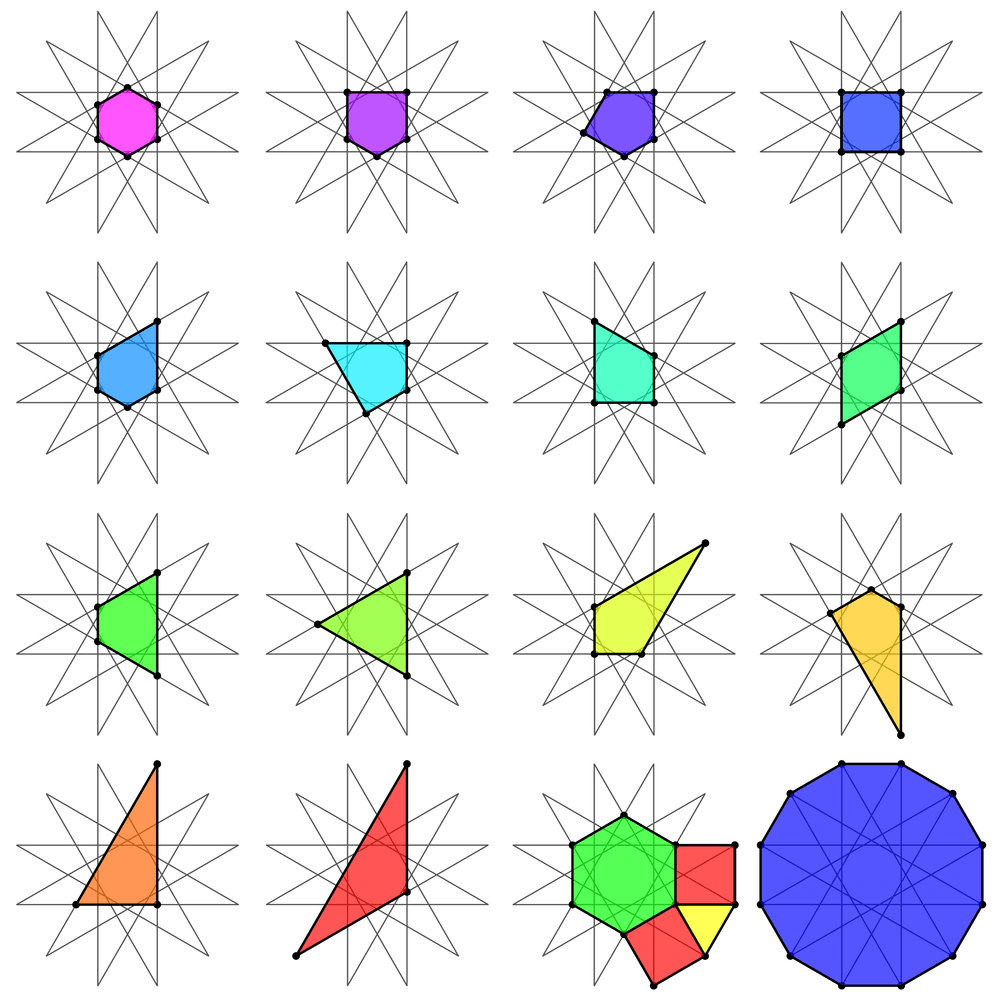

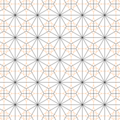

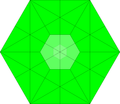

All 14 arbitrary uniform usable vertex regular planigons (VRPs) also hail[5] from the 6-5 dodecagram (where each segment subtends radians, or degrees).

The incircle of this dodecagram demonstrates that all the 14 VRPs are cocyclic, as alternatively shown by circle ambo packings. As a refresher, the ratio of the incircle to the circumcircle is

and the convex hull is precisely the regular dodecagons in the arbitrary uniform tilings! In fact, the equilateral triangle, square, regular hexagon, and regular dodecagon; are shown below along with the VRPs:

Derivation of all possible regular vertex polygons

For edge-to-edge Euclidean tilings, the internal angles of the polygons meeting at a vertex must add to 360 degrees. A regular n-gon has internal angle degrees. There are seventeen combinations of regular polygons whose internal angles add up to 360 degrees, each being referred to as a species of vertex; in four cases there are two distinct cyclic orders of the polygons, yielding twenty-one types of vertex.

In fact, with the vertex (interior) angles , we can find all combinations of admissible corner angles according to the following rules: (i) every vertex has at least degree 3 (a degree-2 vertex must have two straight angles or one reflex angle); (ii) if the vertex has degree , the smallest polygon vertex angles sum to over ; (iii) the vertex angles add to , and must be angles of regular polygons of positive integer sides (of the sequence ). The solution to Challenge Problem 9.46, Geometry (Rusczyk), is in the column Degree 3 Vertex below.[6]

| Degree-6 vertex | Degree-5 vertex | Degree-4 vertex | Degree-3 vertex |

|---|---|---|---|

| * | |||

(a triangle with a hendecagon yields a 13.200-gon, a square with a heptagon yields a 9.3333-gon, and a pentagon with a hexagon yields a 7.5000-gon). Then there are combinations of regular polygons which meet at a vertex.

Only eleven of these can occur in a uniform tiling of regular polygons, given in previous sections. *The cannot coexist with any other vertex types.

In particular, if three polygons meet at a vertex and one has an odd number of sides, the other two polygons must be the same. If they are not, they would have to alternate around the first polygon, which is impossible if its number of sides is odd. By that restriction these six cannot appear in any tiling of regular polygons:

|

|

|

|

|

|

These four can be used in k-uniform tilings:

| Valid

vertex types |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Example

2-uniform tilings |

|

|

|

|

| Valid

Semiplanigons |

.png) V32.4.12 |

.png) |

.png) V32.62 |

.png) V3.42.6 |

| Example

Dual 2-Uniform Tilings (DualCompounds) |

.png) |

|

|

|

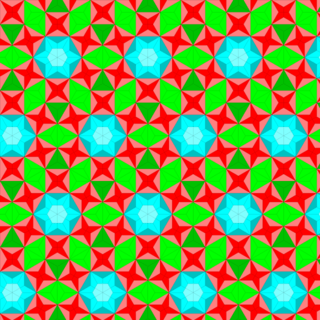

Finally, all regular polygons and usable vertex polygons are presented in the second image below, showing their areas and side lengths, relative to for any regular polygon.

Number of Dual Uniform Tilings

Every dual uniform tiling is in a 1:1 correspondence with the corresponding uniform tiling, by construction of the planigons above and superimposition.

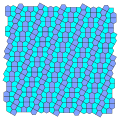

Such periodic tilings may be classified by the number of orbits of vertices, edges and tiles. If there are k orbits of planigons, a tiling is known as k-dual-uniform or k-isohedral; if there are t orbits of dual vertices, as t-isogonal; if there are e orbits of edges, as e-isotoxal.

k-dual-uniform tilings with the same vertex figures can be further identified by their wallpaper group symmetry, which is identical to that of the corresponding k-uniform tiling.

1-dual-uniform tilings include 3 regular tilings, and 8 Laves tilings, with 2 or more types of regular degree vertices. There are 20 2-dual-uniform tilings, 61 3-dual-uniform tilings, 151 4-dual-uniform tilings, 332 5-dual-uniform tilings and 673 6--dualuniform tilings. Each can be grouped by the number m of distinct vertex figures, which are also called m-Archimedean tilings.[7]

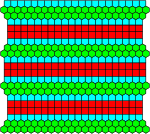

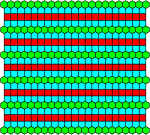

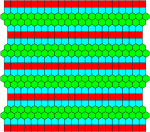

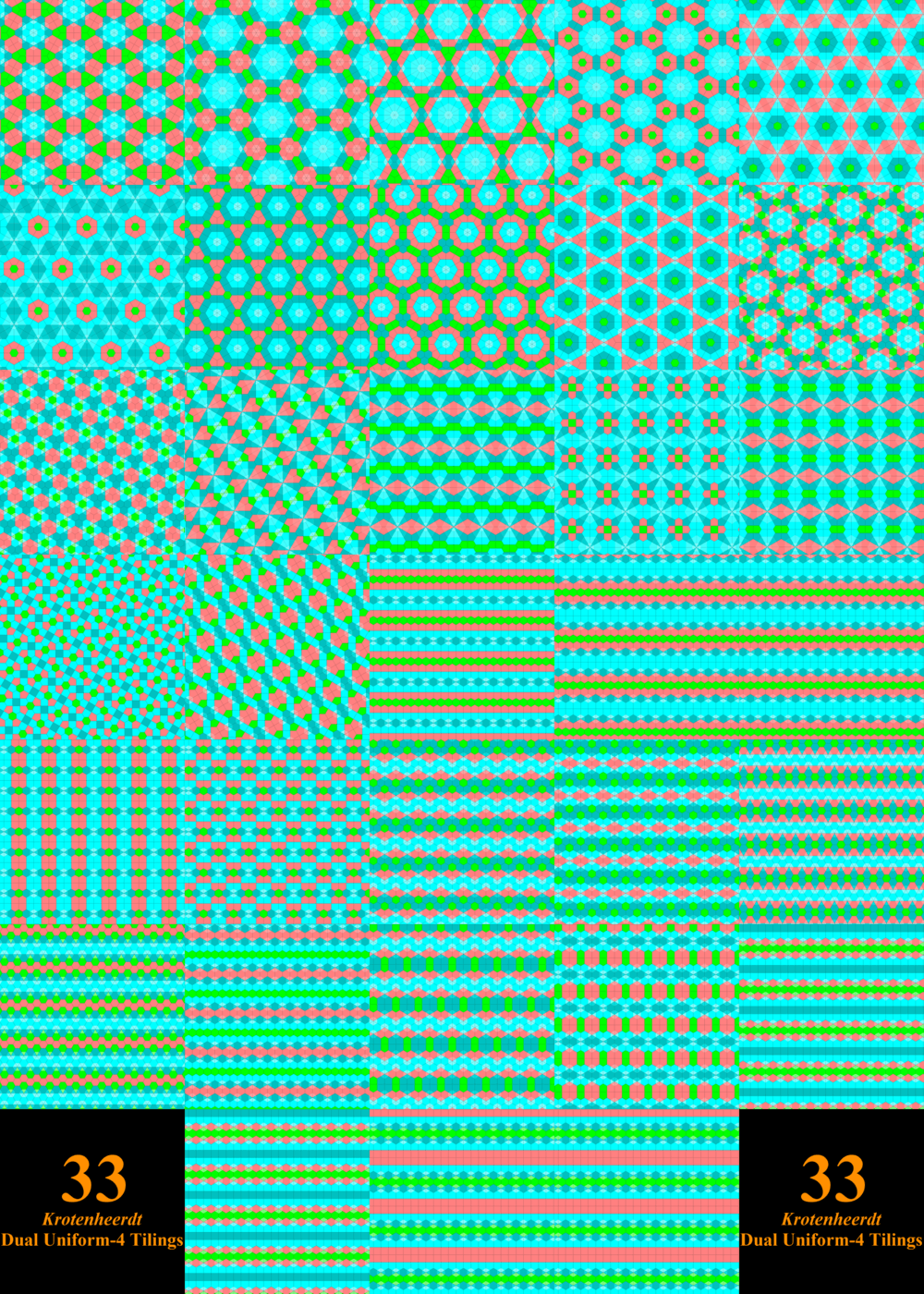

Finally, if the number of types of planigons is the same as the uniformity (m = k below), then the tiling is said to be Krotenheerdt. In general, the uniformity is greater than or equal to the number of types of vertices (m ≥ k), as different types of planigons necessarily have different orbits, but not vice versa. Setting m = n = k, there are 11 such dual tilings for n = 1; 20 such dual tilings for n = 2; 39 such dual tilings for n = 3; 33 such dual tilings for n = 4; 15 such dual tilings for n = 5; 10 such dual tilings for n = 6; and 7 such dual tilings for n = 7.

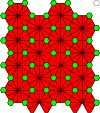

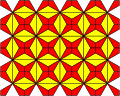

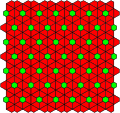

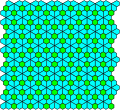

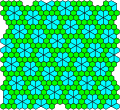

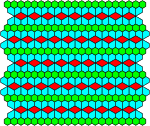

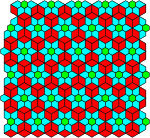

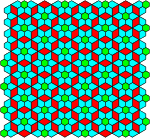

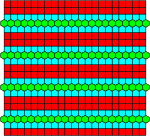

Regular and Laves tilings

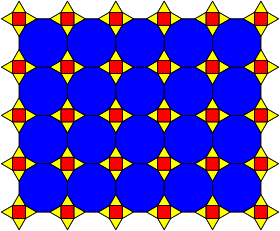

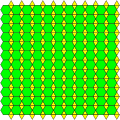

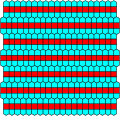

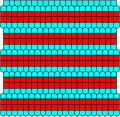

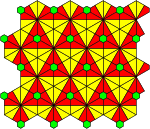

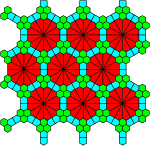

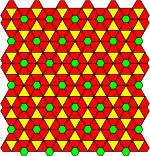

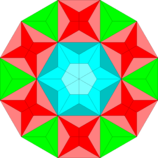

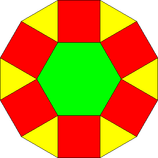

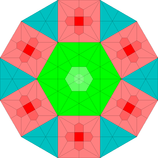

The 3 regular and 8 semiregular Laves tilings are shown, with vertex regular planigons colored inversely to area as in the construction.

| Triangles | Squares | Hexagons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tiling | .png) |

.png) |

.png) |

| Image | _V6.6.6.png) |

_V4.4.4.4.png) |

_V3.3.3.3.3.3.png) |

| Config | V63 | V44 | V36 |

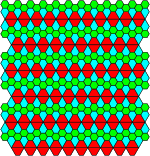

| Triangles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tiling | .png) |

.png) |

.png) |

| Image | _V4.8.8.png) |

_V3.12.12.png) |

_V4.6.12.png) |

| Config | V4.82 | V3.122 | V4.6.12 |

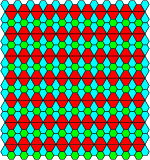

| Quadrilaterals | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tiling | .png) |

.png) |

| Image | _V3.6.3.6.png) |

_V3.4.6.4.png) |

| Config | V(3.6)2 | V3.4.6.4 |

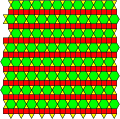

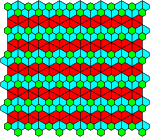

| Pentagons | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tiling | .png) |

.png) |

.png) |

| Image | _V3.3.3.3.6.png) |

_V3.3.4.3.4.png) |

_V3.3.3.4.4.png) |

| Config | V34.6 | V32.4.3.4 | V33.42 |

Higher Dual Uniform Tilings

Insets of Dual Planigons into Higher Degree Vertices

- A degree-six vertex can be replaced by a center regular hexagon and six edges emanating thereof;

- A degree-twelve vertex can be replaced by six deltoids (a center deltoidal hexagon) and twelve edges emanating thereof;

- A degree-twelve vertex can be replaced by six Cairo pentagons, a center hexagon, and twelve edges emanating thereof (by dissecting the degree-6 vertex in the center of the previous example).

|

|

|

| Dual Processes (Dual 'Insets') | ||

|---|---|---|

Krotenheerdt duals with two planigons

Erase When Resolved: also, I see no reason why your images are overall better than mine, which you seem to suggest. We may need a third reader on this...do readers tend not to click on the images to inspect them more? Because in inspection mode, my images are clearer, and in reading mode, your images are clearer.

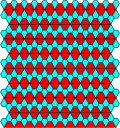

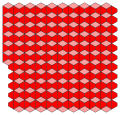

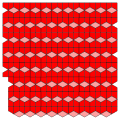

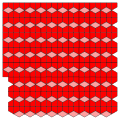

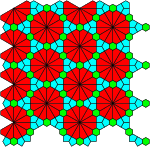

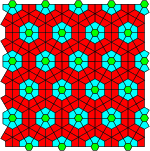

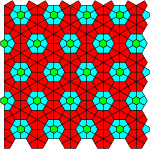

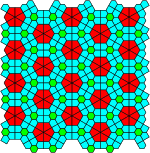

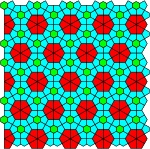

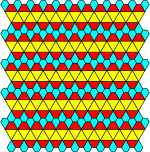

There are 20 tilings made from 2 types of planigons, the dual of 2-uniform tilings (Krotenheerdt Duals):

| p6m, *632 | p4m, *442 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

[V36; V32.4.3.4]   |

[V3.4.6.4; V32.4.3.4   |

[V3.4.6.4; V33.42]   |

[V3.4.6.4; V3.42.6]   |

[V4.6.12; V3.4.6.4]  |

[V36; V32.4.12]  |

[3.12.12; 3.4.3.12]  |

| p6m, *632 | p6, 632 | p6, 632 | cmm, 2*22 | pmm, *2222 | cmm, 2*22 | pmm, *2222 |

[V36; V32.62]   |

[V36; V34.6]1  |

[V36; V34.6]2  |

[V32.62; V34.6]  |

[V3.6.3.6; V32.62]  |

[V3.42.6; V3.6.3.6]]2  |

[3.42.6; 3.6.3.6]1  |

| p4g, 4*2 | pgg, 22× | cmm, 2*22 | cmm, 2*22 | pmm, *2222 | cmm, 2*22 | |

[V33.42; V32.4.3.4]1   |

[V33.42; V32.4.3.4]2   |

[V44; V33.42]1   |

[V44; V33.42]2   |

[V36; V33.42]1   |

[V36; V33.42]2   | |

Krotenheerdt duals with three planigons

_3.426%3B_3.6.3.6%3B_4.6.12.png) (v=6, e=7) |

(v=5, e=6) |

_Final_Project_42.png) (v=5, e=6) |

_3.4.3.12%3B_3.4.6.4%3B_3.122.png) (v=5, e=6) |

_3342%3B_324.12%3B_3.4.6.4.png) (v=6, e=8) |

(v=6, e=7) |

(v=5, e=6) |

_Almost_Popcorn.png) (v=5, e=6) |

(v=5, e=6) |

(v=5, e=6) |

(v=6, e=6) |

(v=6, e=6) |

_Branched_Island_Pods.png) (v=4, e=5) |

_Alternating_Petals.png) (v=4, e=7) |

_Expanded_Snub_Square_with_Hexagon.png) (v=3, e=4) |

_Deltoid_Fish_Scales.png) (v=4, e=6) |

_Snub_Expanded_1_Square.png) (v=4, e=6) |

_Multi_Square_Slab_Offset.png) (v=5, e=7) |

_Multi_Square_Slab_Onset.png) (v=6, e=7) |

_Single_Square_Slab_Offset.png) (v=4, e=5) |

_Single_Square_Slab_Onset.png) (v=5, e=6) |

_Thin_Filled_Hexagon_Slab.png) (v=5, e=8) |

_Gryotrihexagonal_Tiling_Slab_Offset.png) (v=4, e=7) |

_Gryotrihexagonal_Tiling_Slab_Onset.png) (v=5, e=7) |

_One-Layer_Hexagon_Slab.png) (v=5, e=7) |

_Hexagon_with_Triangle_Ribbon_Frame.png) (v=4, e=5) |

_Encased_Rhombi.png) (v=2, e=4) |

(v=2, e=5) |

(v=2, e=3) |

(v=5, e=8) |

(v=3, e=5) |

(v=3, e=6) |

(v=5, e=6) |

(v=4, e=4) |

(v=3, e=3) |

(v=4, e=6) |

(v=5, e=7) |

(v=3, e=5) |

(v=4, e=6) |

Krotenheerdt duals with four planigons

| [33434; 3262; 3446; 63] | [3342; 3262; 3446; 46.12] | [33434; 3262; 3446; 46.12] | [36; 3342; 33434; 334.12] | [36; 33434; 334.12; 3.122] |

| [36; 33434; 343.12; 3.122] | [36; 3342; 33434; 3464] | [36; 3342; 33434; 3464] | [36; 33434; 3464; 3446] | [346; 3262; 3636; 63] |

| [346; 3262; 3636; 63] | [334.12; 343.12; 3464; 46.12] | [3342; 334.12; 343.12; 3.122] | [3342; 334.12; 343.12; 44] | [3342; 334.12; 343.12; 3.122] |

| [36; 3342; 33434; 44] | [33434; 3262; 3464; 3446] | [36; 3342; 3446; 3636] | [36; 346; 3446; 3636] | [36; 346; 3446; 3636] |

| [36; 346; 3342; 3446] | [36; 346; 3342; 3446] | [36; 346; 3262; 63] | [36; 346; 3262; 63] | [36; 346; 3262; 63] |

| [36; 346; 3262; 63] | [36; 346; 3262; 3636] | [3342; 3262; 3446; 63] | [3342; 3262; 3446; 63] | [3262; 3446; 3636; 44] |

| 33 Krotenheerdt-4 Dual | [3262; 3446; 3636; 44] | [3262; 3446; 3636; 44] | [3262; 3446; 3636; 44] | 33 Krotenheerdt-4 Dual |

Krotenheerdt duals with five planigons

There are 15 5-uniform dual tilings with 5 unique planigons.

_33434%3B_3262%3B_3464%3B_3446%3B_63.png) V[33434; 3262; 3464; 3446; 63] |

_Final_Project_52.png) V[36; 346; 3262; 3636; 63] |

_(36%3B_346%3B_3342%3B_3446%3B_46.12).png) V[36; 346; 3342; 3446; 46.12] |

_346%3B_3342%3B_33434%3B_3446%3B_44.png) V[346; 3342; 33434; 3446; 44] |

_36%3B_33434%3B_3464%3B_3446%3B_3636.png) V[36; 33434; 3464; 3446; 3636] |

_36%3B_346%3B_3464%3B_3446%3B_3636.png) V[36; 346; 3464; 3446; 3636] |

_Final_Project_32.png) V[33434; 334.12; 3464;3.12.12; 46.12] |

_36%3B_346%3B_3446%3B_3636%3B_44.png) V[36; 346; 3446; 3636; 44] |

_36%3B_346%3B_3446%3B_3636%3B_44_II.png) V[36; 346; 3446; 3636; 44] |

_36%3B_346%3B_3446%3B_3636%3B_44_III.png) V[36; 346; 3446; 3636; 44] |

_36%3B_346%3B_3446%3B_3636%3B_44_IV.png) V[36; 346; 3446; 3636; 44] |

_36%3B_3342%3B_3446%3B_3636%3B_44.png) V[36; 3342; 3446; 3636; 44] |

_36%3B_346%3B_3342%3B_3446%3B_44.png) V[36; 346; 3342; 3446; 44] |

_36%3B_3342%3B_3262%3B_3446%3B_3636.png) V[36; 3342; 3262; 3446; 3636] |

_36%3B_346%3B_3342%3B_3262%3B_3446.png) [36; 346; 3342; 3262; 3446] |

Krotenheerdt duals with six planigons

There are 10 6-uniform dual tilings with 6 unique planigons.

.png) [V44; V3.4.6.4; V3.4.4.6; 2.4.3.4; V33.42; V32.62] |

.png) ; V34.6; V3.4.4.6; V32.4.3.4; V33.42; V32.62] |

.png) [V44; V34.6; V3.4.4.6; V36; V33.42; V32.62] |

.png) [V44; V3.4.6.4; V3.4.4.6; V(3.6)2; V33.42; V32.46; V36; V33.42; V32.4.3.4] | |

.png) [V36, V3.4.6.4; V3.4.4.6; V32.4.3.4; V33.42; V32.62] |

.png) [V34.6; V3.4.6.4; V3.4.4.6; V32.62; V33.42; V32.4.3.4] |

.png) [V36; V3.4.6.4; V3.4.4.6; V(3.6)2; V33.42; V32.4.12] |

.png) [V36; V3.4.6.4; V3.4.4.6; V34.6; V33.42; V32.4.3.4] |

.png) [V34.6; V3.4.6.4; V3.4.4.6; V(3.6)2; V33.42; V32.4.3.4] |

Krotenheerdt duals with seven planigons

There are 7 7-uniform dual tilings with 7 unique planigons.

_Like_Wallpaper_Group.png) V[36; 33.42; 32.4.3.4; 44; 3.42.6; 32.62; 63] |

_Exotic_Dodecagonal_Unit.png) V[36; 33.42; 32.4.3.4; 34.6; 3.42.6; 32.4.12; 4.6.12] |

_Exotic_Dodecagonal_Unit_ii.png) V[33.42; 32.4.3.4; 3.42.6; 32.62; 32.4.12; 4.6.12] |

_Krotenheerdt_Hexagonal.png) V[36; 32.4.3.4; 44; 3.42.6; 34.6; 3.4.6.4; (3.6)2] |

_Krotenheerdt_Hexagonal_II.png) V[36; 33.42; 32.4.3.4; 34.6; 3.42.6; 3.4.6.4; (3.6)2]1 |

_Rhombile_Dodecahedral.png) V[36; 33.42; 32.4.3.4; 34.6; 3.42.6; 3.4.6.4; 32.4.12] |

_Fish_Scales.png) V[36; 33.42; 32.4.3.4; 34.6; 3.42.6; 3.4.6.4; (3.6)2]2 |

V[36; 33.42; 32.4.3.4; 34.6; 3.42.6; 32.4.12; 4.6.12] |

Strangely enough, the 5th and 7th Krotenheerdt dual uniform-7 tilings have the same vertex types, even though they look nothing alike!

From onward, there are no uniform n tilings with n vertex types, or no uniform n duals with n distinct (semi)planigons.[8]

Fractalizing Dual k-Uniform Tilings

There are many ways of generating new k-dual-uniform tilings from old k-uniform tilings. For example, notice that the 2-uniform V[3.12.12; 3.4.3.12] tiling has a square lattice, the 4(3-1)-uniform V[343.12; (3.122)3] tiling has a snub square lattice, and the 5(3-1-1)-uniform V[334.12; 343.12; (3.12.12)3] tiling has an elongated triangular lattice. These higher-order uniform tilings use the same lattice but possess greater complexity. The dual fractalizing basis for theses tilings is as follows:

| Triangle | Square | Hexagon | Dissected

Dodecagon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape |  |

|

|

|

| Fractalizing

(Dual) |

|

|

|

|

The side lengths are dilated by a factor of :

- Each triangle is replace by three V[3.122] polygons (the unit of the 1-dual-uniform V[3.122] tiling);

- Each square is replaced by four V[3.122] and four V[3.4.3.12] polygons (the unit of the 2-dual-uniform V[3.122; V3.4.3.12] tiling);

- Each hexagon is replaced by six deltoids V[3.4.6.4], six tie kites V[3.4.3.12], and six V[3.122] polygons (the unit of that 3-dual-uniform tiling)

- Each dodecagon is dissected into six big triangles, six big squares, and one central hexagon, all which consist of above.

This can similarly be done with the truncated trihexagonal tiling as a basis, with corresponding dilation of .

| Triangle | Square | Hexagon | Dissected

Dodecagon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape |  |

|

|

|

| Fractalizing

(Dual) |

|

|

|

|

- Each triangle is replace by three V[4.6.12] polygons (the unit of the 1-dual-uniform V[4.6.12] tiling);

- Each square is replaced by one square, four V[33.42] polygons, four V[3.4.3.12] polygons, and four V[32.4.12] polygons (the unit of that Krotenheerdt 4-dual-uniform tiling);

- Each hexagon is replaced by six deltoids V[3.4.6.4] and thirty-six V[4.6.12] polygons (the unit of that 5-dual-uniform tiling)

- Each dodecagon is dissected into six big triangles, six big squares, and one central hexagon, all which consist of above.

Fractalizing Examples

| Truncated Hexagonal Tiling | Truncated Trihexagonal Tiling | |

|---|---|---|

| Dual Fractalizing |

|

.png) |

Miscellaneous

References

- Grünbaum, Branko; Shephard, G. C. (1987). Tilings and Patterns. W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 59, 96. ISBN 0-7167-1193-1.

- Conway, John H.; Burgiel, Heidi; Goodman-Strauss, Chaim (April 18, 2008). "Chapter 21, Naming the Archimedean and Catalan polyhedra and tilings, Euclidean Plane Tessellations". The Symmetries of Things. A K Peters / CRC Press. p. 288. ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5. Archived from the original on 2010-09-19.

- Encyclopaedia of Mathematics: Orbit - Rayleigh Equation , 1991

- Ivanov, A. B. (2001) [1994], "Planigon", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

- "THE BIG LIST SYSTEM OF TILINGS OF REGULAR POLYGONS". THE BIG LIST SYSTEM OF TILINGS OF REGULAR POLYGONS. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- Rusczyk, Richard. (2006). Introduction to geometry. Alpine, CA: AoPS Inc. ISBN 0977304523. OCLC 68040014.

- k-uniform tilings by regular polygons Archived 2015-06-30 at the Wayback Machine Nils Lenngren, 2009

- "11,20,39,33,15,10,7 - OEIS". oeis.org. Retrieved 2019-06-26.

- Planigon tessellation cellular automata Alexander Korobov , 30 September 1999

- B. N. Delone, “Theory of planigons”, Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Mat., 23:3 (1959), 365–386

.png)