Placenta cake

Placenta cake is a dish from ancient Greece and Rome consisting of many dough layers interspersed with a mixture of cheese and honey and flavored with bay leaves, baked and then covered in honey.[1][2] The dessert is mentioned in classical texts such as the Greek poems of Archestratos and Antiphanes, as well as the De Agri Cultura of Cato the Elder.[2]

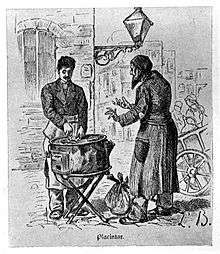

A Greek plăcintă-maker in Bucharest in 1880. | |

| Type | Pie |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome |

| Main ingredients | Flour and semolina dough, cheese, honey, bay leaves |

| Variations | plăcintă, palatschinke |

Etymology

The Latin word placenta is derived from the Greek plakous (Ancient Greek: πλακοῦς, gen. πλακοῦντος – plakountos, from πλακόεις - plakoeis, "flat") for thin or layered flat breads.[3][4][5]

The cake gave its name to the organ, owing to the latter's shape.

History

In circa 350 BC, the ancient Greek poet Archestratos registered plakous as a dessert (or second table delicacy) served with nuts and dried fruits; the honey-drenched Athenian version of plakous was commended by the poet.[2] The Greek comic poet Antiphanes (fl. 4th century BC), a contemporary of Archestratos, provided an ornate description of plakous and mentioned wheat flour and goat's cheese as its key ingredients.[2][6] Later in 160 BC, Cato the Elder provided a recipe for placenta in his De Agri Cultura that Andrew Dalby considers, along with Cato's other dessert recipes, to be in the "Greek tradition", possibly copied from a Greek cookbook.[2][7] Cato writes:

A number of modern scholars suggest that the Greco-Roman dessert's Eastern Roman (Byzantine) descendants, plakountas tetyromenous ("cheesy placenta") and koptoplakous (Byzantine Greek: κοπτοπλακοῦς), are the ancestors of modern tiropita (börek or banitsa) and baklava respectively.[1][9] The name placenta (Greek: πλατσέντα) is used today on the island of Lesbos in Greece to describe a baklava-type dessert of layered pastry leaves containing crushed nuts that is baked and then covered in honey.[10][11] Through its Greek name plakountos, the dessert was adopted into Armenian cuisine as plagindi, plagunda, and pghagund, all "cakes of bread and honey."[12] From the latter term came the later Arabic name iflaghun, which is mentioned in the medieval Arab cookbook Wusla ila al-habib as a specialty of the Cilician Armenians settled in southern Asia Minor and settled in the neighboring Crusader kingdoms of northern Syria.[12] Thus, the dish may have traveled to the Levant in the Middle Ages via the Armenians, many of whom migrated there following the first appearance of the Turkish tribes in medieval Anatolia.[13] Other variants of the Greco-Roman dish survived into the modern era in the form of the Romanian plăcintă and the Viennese palatschinke.[2]

See also

References

Citations

- Faas 2005, pp. 184–185.

- Goldstein 2015, "ancient world": "The next cake of note, first mentioned about 350 B.C.E. by two Greek poets, is plakous. [...] At last, we have recipes and a context to go with the name. Plakous is listed as a delicacy for second tables, alongside dried fruits and nuts, by the gastronomic poet Archestratos. He praises the plakous made in Athens because it was soaked in Attic honey from the thyme-covered slopes of Mount Hymettos. His contemporary, the comic poet Antiphanes, tells us the other main ingredients, goat’s cheese and wheat flour. Two centuries later, in Italy, Cato gives an elaborate recipe for placenta (the same name transcribed into Latin), redolent of honey and cheese. The modern Romanian plăcintă and the Viennese Palatschinke, though now quite different from their ancient Greek and Roman ancestor, still bear the same name."

- Lewis & Short 1879: placenta.

- Liddell & Scott 1940: πλακοῦς.

- Stevenson & Waite 2011, p. 1095, "placenta".

- Dalby 1998, p. 155: "Placenta is a Greek word (plakounta, accusative form of plakous 'cake'). 'The streams of the tawny bee, mixed with the curdled river of bleating she-goats, placed upon a flat receptacle of the virgin daughter of Demeter [honey, cheese, flour], delighting in ten thousand delicate toppings – or shall I simply say plakous? I'm for plakous' (Antiphanes quoted by Athenaeus 449c)."

- Dalby 1998, p. 21: "We cannot be so sure why there is a section of recipes for bread and cakes (74-87), recipes in a Greek tradition and perhaps drawing on a Greek cookbook. Possibly Cato included them so that the owner and guests might be entertained when visiting the farm; possibly so that proper offerings might be made to the gods; more likely, I believe, so that profitable sales might be made at a neighbouring market."

- Cato the Elder. De Agri Cultura, 76.

- Salaman 1986, p. 184; Vryonis 1971, p. 482.

- Τριανταφύλλη, Κική (17 October 2015). "Πλατσέντα, από την Αγία Παρασκευή Λέσβου". bostanistas.gr. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Γιαννέτσου 2014, p. 161: "Η πλατσέντα είναι σαν τον πλακούντα των αρχαίων Ελλήνων, με ξηρούς καρπούς και μέλι."

- Perry 2001, p. 143.

- Bozoyan 2008, p. 68.

Sources

- Bozoyan, Azat A. (2008). "Armenian Political Revival in Cilicia". In Hovannisian, Richard G.; Payaslian, Simon (eds.). Armenian Cilicia. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers. pp. 67–78. ISBN 1568591543.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dalby, Andrew (1998). Cato. On Farming (De Agricultura). A Modern Translation with Commentary. Totnes: Prospect.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Faas, Patrick (2005). Around the Roman Table: Food and Feasting in Ancient Rome. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226233472.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Γιαννέτσου, Βασιλεία Λούβαρη (2014). Τα Σαρακοστιανά: 50 συνταγές για τη Σαρακοστή και τις γιορτές της από τη MAMAVASSO. Georges Yannetsos.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldstein, Darra, ed. (2015). The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199313393.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879). A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perry, Charles (2001). "Studies in Arabic Manuscripts". In Rodinson, Maxime; Arberry, Arthur John (eds.). Medieval Arab Cookery. Totnes: Prospect Books. pp. 91–163. ISBN 0907325912.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Salaman, Rena (1986). "The Case of the Missing Fish, or Dolmathon Prolegomena (1984)". In Davidson, Alan (ed.). Oxford Symposium on Food & Cookery 1984 & 1985, Cookery: Science, Lore and Books Proceedings. London: Prospect Books Limited. pp. 184–187.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stevenson, Angus; Waite, Maurice, eds. (2011). Concise Oxford English Dictionary: Luxury Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199601119.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vryonis, Speros (1971). The Decline of Medieval Hellenism in Asia Minor and the Process of Islamization from the Eleventh through the Fifteenth Century. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52-001597-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "American Pie". American Heritage. April–May 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-07-12. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

The Romans refined the recipe, developing a delicacy known as placenta, a sheet of fine flour topped with cheese and honey and flavored with bay leaves.