Pietro di Donato

Pietro Di Donato (April 3, 1911–January 19, 1992) was an American writer and bricklayer best known for his novel, Christ in Concrete, which recounts the life and times of his bricklayer father, Geremio, who was killed in 1923 in a building collapse. The book, which portrayed the world of New York's Italian-American construction workers during The Great Depression,[1] was hailed by critics in the United States and abroad as a metaphor for the immigrant experience in America,[2] and cast di Donato as one of the most celebrated Italian American novelists of the mid-20th century.[1]

Pietro di Donato | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Pietro di Donato April 3, 1911 West Hoboken, New Jersey (now Union City) |

| Died | January 19, 1992 (aged 80) Stony Brook, New York |

| Occupation | Novelist, reporter, bricklayer |

| Notable works | Christ in Concrete, Immigrant Saint: The Life of Mother Cabrini |

Early life

Di Donato was born April 3, 1911 in West Hoboken, New Jersey (now Union City) to Geremio, a bricklayer, and Annunziata Chinquina. He had seven other siblings. His parents had emigrated from the town of Vasto, in the region of Abruzzo in Italy.[2][3]

On March 30, 1923, Geremio di Donato died when a building collapsed on him, burying him in concrete. Pietro, who was twelve at the time, left school in the seventh grade to become a construction worker in the trade union in order to help support his family. He retained his membership in the union his entire life. His father's death and his life growing up as an immigrant in West Hoboken were the inspiration for his writings. When his mother died a few years later, Pietro assumed full responsibility for providing for his family. Though he had little formal education, during a strike in the building trades he had wandered into a library and discovered French and Russian novels, becoming particularly fond of Émile Zola. He also took night classes at City College in construction and engineering. The family was eventually able to move to Northport, Long Island, where he continued to work as a mason, and was inspired by Zola's work to write about his own experiences in the Italian immigrant community.[2][3]

Career

Christ in Concrete was published as a short story in the March 1937 issue of Esquire magazine, and was subsequently expanded into a full-length, blue-collar proletarian novel with an introduction by Arnold Gingrich.[3] The book remained on best-seller lists for months, and was eventually chosen for the Book of the Month Club main selection, edging out John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath, which was published the same year. According to Allen Barra in an interview for Salon.com, the novel became an instant classic, and standard reading for second-generation Italian-Americans. Screenwriter Ben Barzman, who wrote the screenplay into which the novel was adapted, called it "the first of its kind", and The National Italian American Foundation called it "rare." Charles Poore, writing in The New York Times on Sept. 15, 1939, described the book as "eloquent" and "Italian to the core...by turns operatic, lyrical, ferocious and hilarious",[2] and commented, "It was something rare, a proletarian novel written by a proletarian."[1] It was included in Edward O'Brien's Best Short Stories of 1938.[3]

The novel was adapted into the 1949 film Give Us This Day (U.S. title: "Christ in Concrete"), written by Ben Barzman, and directed by blacklisted filmmaker Edward Dmytryk. It won awards at festivals across Europe, such as the 1949 Venice Film Festival,[3] though it was effectively banned from the United States at the time, and was only shown in a single theatre.

In 1958 di Donato wrote his second novel, a sequel to Christ in Concrete called This Woman. It continued the story of di Donato's life following his father's death, and focused on his spiritual conflict and obsessive sensuality. In 1960 a third book in the same tradition called Three Circles of Light, focused on di Donato's childhood in the years prior to his father's death.[3] That same year, di Donato published The Immigrant Saint: The Life of Mother Cabrini, a fictionalized account of Frances Xavier Cabrini, the first United States citizen to be canonized. It was well-received, and named a main selection of the Catholic Book Club and Maryknoll Book Club in 1961. Though critics felt that di Donato's later works never achieved the quality of Christ in Concrete,[2] Immigrant Saint became a cult classic.[1]

The following year di Donato published The Penitent, an account of contrition and spiritual rebirth of the man who killed the twelve-year-old St. Maria Goretti. His last book-length publication was Naked as an Author, a collection of reprinted stories from his longer works.[3]

In 1978 his article on the kidnapping and murder of Aldo Moro (president of the Christian Democratic Party of Italy), titled "Christ in Plastic", appeared in Penthouse magazine, and won the Overseas Press Club. Di Donato later adapted the article into a play entitled Moro.[1][3]

Personal life

Following the death of his father, Di Donato became the breadwinner for his mother and seven siblings. He joined the Young Communist League in response to the execution of Sacco and Vanzetti.[4] In 1942, after registering as a conscientious objector to World War II, Di Donato, while working as a forester in a Cooperstown, New York Quaker camp,[3] met former showgirl Helen Dean. They were married in 1943, in a ceremony performed by New York City's Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, and moved to Setauket, Long Island. They had two sons, Peter and Richard, and a stepdaughter, Harriet Mull.[2]

Death and legacy

Di Donato died of bone cancer January 19, 1992 in Stony Brook, Long Island, with his last unfinished novel, Gospels, unpublished.[2][3]

He is the subject of the book Pietro DiDonato, the Master Builder by Matthew Diomede, published by Bucknell University Press in 1995.

Keeping Pietro di Donato's legacy alive, his son Richard is now maintaining a comprehensive website, detailing events not prior published, at www.PietroDiDonato.com .

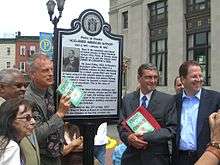

The town of Union City, New Jersey dedicated Pietro di Donato Square on May 22, 2010. The Square, which is located at Bergenline Avenue and 31st Street, where Donato once lived, includes a plaque commemorating his life and work. Di Donato's son, Richard, was present at the ceremony.[5]

Bibliography

- Christ in Concrete (1939)

- This Woman (1958)

- Immigrant Saint: The Life of Mother Cabrini (1960)

- Three Circles of Light (1960)

- The Penitent (1962, biography of Maria Goretti)

- Naked Author (1970)

- The American Gospels (2000).

References

- Rosero, Jessica. "Native sons and daughters: Tragedy Led Italian Novelist in UC to Pen Literary Classic; Christ in Concrete." Hudson Reporter February 12, 2006.

- Severo, Richard. "Pietro di Donato Is Dead at 80; Wrote of Immigrants' Experience", The New York Times, January 21, 1992. Accessed December 10, 2007. "Mr. di Donato was born on April 3, 1911, in West Hoboken, N.J. His family had immigrated to the United States from Vasto, in the Abruzzi region of Italy."

- Pietro di Donato: Acclaimed American Author; Union City Historical Marker Dedication Ceremony Program; May 22, 2010

- Carol Strickland, "An Immigrant's Pain in Concrete," New York Times, October 14, 1990, https://www.nytimes.com/1990/10/14/nyregion/an-immigrant-s-pain-in-concrete.html?pagewanted=all

- "UC recognizes history with dedication and marker" Hudson Reporter; May 23, 2010