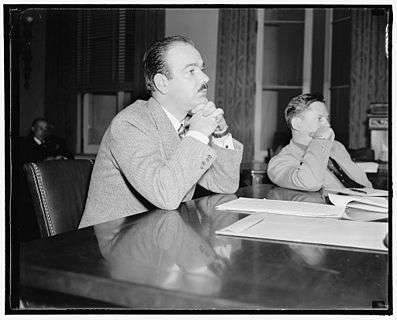

Arnold Gingrich

Arnold W. Gingrich (December 5, 1903 – July 9, 1976) was the editor of, and, along with publisher David A. Smart and Henry L. Jackson, co-founder of Esquire magazine. Among his other projects was the political/newsmagazine Ken.

Influence

Gingrich created Esquire in 1933 and remained its editor until 1945. He returned as publisher in 1952, serving in this role until his death in 1976.[1] For several years he left the post of editor vacant while several young editors competed for it. The two most serious contenders were Harold Hayes and Clay Felker. Hayes won, and Felker went on to found New York magazine. During the Hayes-Gingrich era, Esquire played a leading role in launching the New Journalism, publishing writers like Tom Wolfe and fellow fraternity brother, Gay Talese.[2]

Biography

Gingrich was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, of Mennonite parents in 1903. He attended the University of Michigan where he was a member of Phi Sigma Kappa fraternity, and was noted as a member of the class of 1925.[3] Gingrich brought numerous skills and interests to bear in the formation of Esquire magazine, notably his skill in editing, identification of talent and in publishing. His partner, David Smart led the business side of the magazine with Henry Jackson responsible for the fashion section, making up a more substantial portion of the magazine in its first fifteen years. Over his four decade career, Gingrich published such authors as Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, John Steinbeck, John Dos Passos, Garry Wills, Truman Capote, and Norman Mailer. He was also one of the few magazine editors to publish F. Scott Fitzgerald regularly in the late 1930s, including Fitzgerald's The Pat Hobby Stories.[4] Gingrich also published stories by Jack Woodford, whom he befriended when they worked together at an advertising agency in the late 1920s. He wrote the introduction to Woodford's famous book on writing and publishing, Trial and Error.

Esquire's origin and influence

The magazine's name Esquire was inspired by a letter from Gingrich's friend Robert Klark Graham, facetiously addressing him as "Arnold Gingrich, Esquire."[5] The magazine he created set the template for future men's magazines of the mid-century period; for example, Playboy, a variation, essentially Esquire with nude photographs (Esquire had famously published a series of "Varga Girl" paintings and other "cheesecake" imagery since its founding). Similar periodicals include GQ (originally Gentlemen's Quarterly), Field & Stream, Popular Mechanics and Popular Science. Further afield, even The Atlantic and other regional and national publications exhibit styling and content first evidenced in the pages of Esquire. Indeed, Esquire was one of the forerunners of this genre, blending aspects of traditional, if upper-crust masculine pastimes such as armchair discussions of Ivy League pedigree, East Coast fraternalism, and literary interest with "the sporting life," such as horses and angling, fashion, love of tobacco and whiskey, and admiration for the feminine. More recently Maxim has continued this tradition with a more edgy appeal to Gen-Xers and millennials.

Later life

His autobiography, Toys Of A Lifetime, with illustrations by Leslie Saalburg, was published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1966. It has long been out of print. In it, Gingrich recounts his experience with cars (he owned several notable Bentleys), including a classic R-series and S-series "Countryman" (obtained through the late J.S. Inskip in Manhattan), as well as an early Volkswagen. Other interests include transatlantic liners (notably the Normandie), French hotels, Dunhill pipes and Balkan Sobranie tobacco, clothes and all manner of other possessions and accommodations.

Gingrich was an accomplished fly fisherman, writing several books on the subject and lifestyle of the gentleman angler.

Gingrich was also an accomplished violinist. He would arrive at his office hours early in order to practice before the staff arrived, participated in amateur chamber music ensembles, and owned a number of highly prized instruments.[6] He published a musical memoir titled "A Thousand Mornings of Music: The Journal of an Obsession with the Violin."[7]

He died in 1976 at his home in Ridgewood, New Jersey.[8]

Contributions to angling literature

Gingrich was an avid fly fisherman and contributed much to the literature of the sport.

- Gingrich, Arnold (1965). The Well Tempered Angler. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. More a reflection on the fishing life than a how-to manual, though it does contain practical advice on light tackle fly fishing, and a useful bibliography.[9]

- The Theodore Gordon Flyfishers (1996). Arnold Gingrich (ed.). American Trout Fishing. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. American Trout Fishing is the trade press edition of the Gordon Garland, a compilation of stories and history about American Trout fishing and is dedicated to Theodore Gordon. Noted fly fishing authors, including Lee Wulff, Roderick Haig-Brown, Ernie Schwiebert, Dana Lamb, Joe Brooks and many others, contributed to this work.[10][11]

- Gingrich, Arnold (1973). The Joys of Trout. New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-517-50584-3. Listed as one of the modern "classics" of angling in the University of New Hampshire Library Milne Angling Collection.[12]

- Gingrich, Arnold (1974). The Fishing In Print-A Guided Tour Through Five Centuries of Angling Literature. New York: Winchester Press. In The Fishing In Print, Gingrich surveys the major pieces of classic and modern fly fishing literature up through the 1950s. It is an excellent read to get a better understanding of the evolution of the various styles of fly fishing—wet, nymphs, dry, etc. as originally written about by the likes of Halford, Skues, Gordon and Jennings along with many others.

References

- Carol Polsgrove, It Wasn't Pretty, Folks, But Didn't We Have Fun? Esquire in the Sixties (1995), pp. 25-26.

- Polsgrove, It Wasn't Pretty, Folks, But Didn't We Have Fun?

- Phi Sigma Kappa Alumni Directory (2001), Indianapolis, Indiana: Phi Sigma Kappa Fraternity, 2001, p. 258

- Paul Greenberg (2008-02-10). "Fitzgerald vs. Hollywood". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- Graham, Robert Klark. R.K.G. Scott-Townsend, 1996. p. 19. ISBN 1-878465-17-1.

- S.Applebaum, "The Way They Play, Vol. 3", Paganninian Pubs. 1975

- https://www.amazon.com/Thousand-Mornings-Music-Journal-Obsession/dp/B0006C0B24

- Carmody, Deirdre. "Arnold Gingrich, 72, Dead; Was a Founder of Esquire", The New York Times, July 10, 1976. Accessed November 17, 2017. "Arnold Gingrich, one of the founders of Esquire magazine in 1933 and its principal guiding light in most of the years since then, died of cancer yesterday at his home in Ridgewood, N.J."

- Johnson, George, New & Noteworthy, October 4th, 1987, New York Times Book Review

- Serviente, Barry (1996). Angler's Art Catalog. Plainfield, PA: The Anglers Art. pp. 95–96.

- Gingrich, Arnold (1974). The Fishing In Print-A Guided Tour Through Five Centuries of Angling Literature. New York: Winchester Press. pp. 317–18.

- University of New Hampshire Library, Milne Angling Collection Selected Highlights Archived 2007-04-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Miller, Warren D. (Spring 1994). "A Morning in the Life of America's Esquire" (PDF). The American Fly Fisher. American Fly Fishing Museum. 20 (2): 2–9. Retrieved 2014-11-16.