Pierre Hincelin

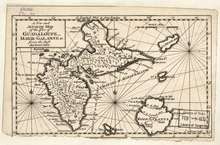

Pierre Hincelin (or Hencelin; died 15 June 1695) was a French soldier who was the kings lieutenant on Guadeloupe. He fought on Antigua in 1666 during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. He was governor of Guadeloupe from 1677 to 1694. The Nine Years' War broke out in 1688 and Guadeloupe was invaded by the English in 1691. The French defenders were outnumbered and retreated, but the effect of disease, heavy rain and the arrival of French reinforcements led to the English leaving after a few weeks.

Pierre Hincelin | |

|---|---|

| Governor of Guadeloupe | |

| In office 5 July 1677 – 1694 | |

| Preceded by | Charles François du Lyon de Baas de l'Herpinière (?) |

| Succeeded by | Charles Auger |

| Personal details | |

| Died | 15 June 1695 Guadeloupe |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | Soldier, colonial administrator |

Early years

& Nevis

Hincelin was the brother-in-law of Charles Houël du Petit Pré.[1] Houël was governor of Guadeloupe from 1643 to 1656.[2] Houël had taken leave in Paris, where he married Mlle. Hincelin. They returned in 1656.[3] Hincelin was appointed the king's lieutenant on Guadeloupe.[1] Houël signed a solemn peace treaty with the Island Caribs in 1660. It proved more difficult to maintain peace within the leading families of Guadeloupe. The cantankerous governor soon stirred up quarrels with his brother and his nephews.[4] Hincelin thought he could take advantage of the situation and almost came to blows with Houël. The king was dragged into the quarrel, and on 25 May 1660 wrote a letter to the aging lieutenant-general Phillippe de Longvilliers de Poincy asking him to restore peace on Guadeloupe and to stop the proceedings of Houeil against the widow of Jacques de Boisseret and her children.[5]

Alexandre de Prouville de Tracy, appointed lieutenant-general of the American mainland and islands, left La Rochelle on 26 February 1664, took 200 colonists under Antoine Lefèbvre de La Barre to Cayenne, then sailed north to reach Martinique on 3 June 1664. There he published a 26-point ordinance spelling out punishments for offenses such as blasphemy and miscegenation.[6] Tracy reached Basse-Terre, Guadeloupe on 23 June 1664, and instructed Houäl, d'Erbray and Théméricourt to leave for France. He made Claude François du Lyon governor of Guadeloupe and Gabriel de Folio, sieur des Roses commander of Marie-Galante. Hincelin was authorized to remain in Guadeloupe to look after the interests of his brother-in-law.[7]

During the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1666–67) La Barre, newly appointed lieutenant-general arrived in the Antilles late in 1866 with a fleet and 400 soldiers.[8] A council of war was held on Martinique in late 1866 in which it was agreed to attack Antigua.[9] A fleet under the command of La Barre arrived in Antigua on 4 November 1666.[10] After overcoming some resistance governor Robert de Clodoré of Martinique accepted the English capitulation on 10 November 1666.[11] The French then left for Saint Christophe.[12] On 30 November 1666 Clodoré returned to Saint John's harbor, Antigua with almost 1,000 men. He learned that 900 Englishmen from Barbuda and Nevis had gathered in the northern district of Pope's Head and were being joined by Antiguan settlers. Clodoré took his fleet to Pope's head where he disembarked his force, with Hencelin and Blondel as seconds in command. They at once charged into the English force which fled in disarray and escaped by sea. There were no French casualties.[10]

Governor of Guadeloupe

Charles François du Lyon, governor of Guadeloupe, died in July 1677. Hincelin was named provisional governor in his place.[1] He became governor of Guadeloupe on 5 July 1677 under Charles de Courbon de Blénac, governor and lieutenant-general of the islands and mainland of America. [13] The king named M. de Baaz de l'Herpinière, nephew of the former governor general Jean-Charles de Baas, as the successor to Du Lion. When that nomination failed to take effect, Hincelin was confirmed as governor.[14]

During the Nine Years' War (1688–97) the governor general Blénac resigned on 29 January 1690 after criticism of his lack of response to the English attacks on Saint Barthélemy, Marie-Galante and Saint Martin, and returned to France to defend himself at court.[15] François d'Alesso d'Éragny was appointed his successor in May 1690, but the marquis de Seignelay did not treat his departure as a matter of urgency.[16] D'Eragny arrived in Martinique on 5 February 1691 with 14 ships and began to strengthen the defenses.[15]

In April 1691 an English fleet under Commodore Wright and Governor General Christopher Codrington disembarked troops in Marie-Galante, which they captured from the 240-man garrison under governor Charles Auger. On 1 May 1691 the English fleet arrived off the west of Guadeloupe and bombarded the town of Baillif to the north of Basse-Terre before disembarking further north at Anse à la Barque.[17] Hincelin was suffering from severe hydropsy.[18] He was ill and bedridden, thought the English were bluffing and sent only a small force north to watch the English. Codrington advanced south against weak resistance.[17] 400 men under the king's lieutenant Robert Cloche de La Malmaison delayed the English before being forced back.[18] On 3 May the English defeated a French force at the Duplessis River, and resistance collapsed.[17]

The French retreated south past Baillif and Basse-Terre.[17] Some of the French troops took refuge in Fort Saint-Charles(fr) and were besieged.[15] The next day the English set fire to Basse-Terre.[17] On 23 May Codrington, whose force was becoming weakened by disease, heard that a French fleet under Jean-Baptiste Ducasse had arrived with reinforcements.[19] The French force regained Marie-Galante and then started disembarking reinforcements in the northeast Grand-Terre district.[20] Codrington hastily reembarked leaving behind cannons and some of his wounded.[21] The English left the island on 25 May.[20]

Hincelin, who had long been ill, died on 15 June 1695. He left his considerable fortune to the four religious orders on Guadeloupe.[22] He was succeeded as governor of Guadeloupe by Charles Auger, who took office on 15 July 1695.[2]

Notes

- Boyer-Peyreleau 1823, pp. 267–268.

- Cahoon.

- Boyer-Peyreleau 1823, p. 228.

- Boyer-Peyreleau 1823, p. 232.

- Boyer-Peyreleau 1823, p. 233.

- Lacour 1855, p. 144.

- Lacour 1855, p. 146.

- Boucher 2010, p. 183.

- Antigua and the Antiguans 1844, p. 24.

- Marley 2008, p. 256.

- Antigua and the Antiguans 1844, p. 28.

- Antigua and the Antiguans 1844, p. 29.

- Chronologie: Regime Royal, p. 189.

- Boyer-Peyreleau 1823, p. 268.

- Marley 2005, p. 171.

- Pritchard 2004, p. 306.

- Marley 2008, p. 320.

- Boyer-Peyreleau 1823, p. 271.

- Marley 2008, pp. 320–321.

- Marley 2008, p. 321.

- Lacour 1855, p. 195.

- Lacour 1855, p. 196.

Sources

- Antigua and the Antiguans: A Full Account of the Colony and Its Inhabitants, Saunders and Otley, 1844, ISBN 978-1-108-02776-2, retrieved 2018-08-18

- Boucher, Philip P. (2009-04-27), Cannibal Encounters: Europeans and Island Caribs, 1492–1763, JHU Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-9099-4, retrieved 2018-08-17

- Boucher, Philip P. (2010-12-29), France and the American Tropics to 1700: Tropics of Discontent?, JHU Press, ISBN 978-1-4214-0202-4, retrieved 2018-08-21

- Boyer-Peyreleau, Eugène-Édouard (1823), Les Antilles françaises, particulièrement la Guadeloupe, depuis leur découverte jusqu'au 1er janvier 1823 (in French), Brissot-Thivars, retrieved 2018-09-22

- Cahoon, Ben, "Gaudeloupe", Worldstatesmen.org, retrieved 2018-09-22

- "Chronologie: Regime Royal", Annuaire de la Guadeloupe et dépendances (in French), Imprimerie du Gouvernement, 1860, retrieved 2018-09-23

- Goslinga, Cornelis C. (2012-12-06), A Short History of the Netherlands Antilles and Surinam, Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 978-94-009-9289-4, retrieved 2018-08-15

- Lacour, Auguste (1855), Histoire de la Guadeloupe (in French), E. Kolodziej, retrieved 2018-09-22

- Marley, David (2005), Historic Cities of the Americas: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-027-7, retrieved 2018-09-01

- Marley, David (2008), Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere, 1492 to the Present, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-100-8, retrieved 2018-09-23

- Pritchard, James S. (2004-01-22), In Search of Empire: The French in the Americas, 1670-1730, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82742-3, retrieved 2018-09-21