Pictones

The Pictones were a Gallic tribe of the La Tène and Roman periods, dwelling south of the Loire river, in the modern départements of Vendée, Deux-Sèvres and Vienne.[1]

Name

They are mentioned as Pictones by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC) and Pliny (1st c. AD),[2][3] as Píktones (Πίκτονες) by Ptolemy (2nd c. AD),[4] and as Pictonici by Ausonius (4th c. AD).[5][6] They are also known as Pictavi from the 2nd c. AD, in the Notitia Galliarum and in Ammianus Marcellinus's Res Gestae (4th c. AD).[6][1]

The city of Poitiers, attested as urbis Pictavorum ca. 356 AD (Pictavis in 400–410, Peitieus [*Pectievs] in 1071–1127), and the region of Poitou are named after the Gallic tribe.[7]

Geography

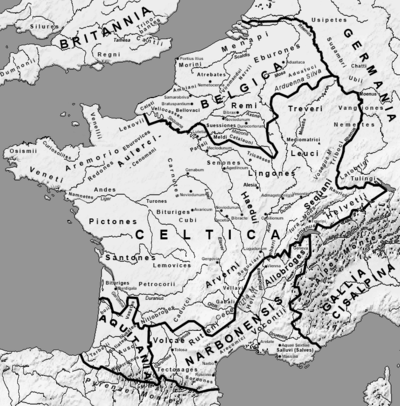

The territory of the Pictones was located south-east of the Namnetes, west of the Bituriges Cubi, north-west of the Lemovices, and north of the Santones.[1] During the reign of Augustus (27 BC – 14 AD), the Pictones were included in the larger province of Gallia Aquitania, along with most of western Gaul.

History

La Tène period

The Pictones minted coins from the end of the 2nd century BC. The tribe was first noted in written sources when encountered by Julius Caesar. Caesar depended on their shipbuilding skills for his fleet on the Loire.[8] Their chief town Lemonum, the Celtic name of modern-day Poitiers (Poitou),[9] is located on the south bank of the Liger. Ptolemy mentions a second town, Ratiatum (modern Rezé).[10]

The political organization of the region was modeled on the royal Celtic system. Duratios was king of the Pictones during the Roman conquest, but his power waned thanks to the poor skill of his generals. However, the Pictones frequently aided Julius Caesar in naval battles, particularly with the naval victory over the Veneti on the Armorican peninsula.

Roman rule

The Pictones had felt threatened by the migration of the Helvetians toward the territory of the Santones and supported the intervention of Caesar in 58 BC. Though fiercely independent, they collaborated with Caesar, who noted them as one of the more civilized tribes. Nevertheless, 8000 men were sent to aid Vercingetorix, the chieftain who led the Gaulish rebellion in 52 BC. This act divided the Pictones and the region was the location of a later uprising, especially around Lemonum. This was later quelled by legate Gaius Caninius Rebilus and finally by Caesar himself.

The Pictones benefited from Roman peace, notably through many urban constructions such as aqueducts and temples. A thick wall built in the 2nd century AD encircles the city of Lemonum and is one of the distinguishing architectural forms of Gaulish antiquity. However, the Pictones were not Romanized in depth. Lemonum quickly adopted Christianity in the first two centuries AD.

The region was known for its timber resources and occasionally traded with the Roman province of Transalpine Gaul. Additionally, the Pictones traded with the British Isles from the harbor of Ratiatum (Rezé), which served as an important port linking Gaul and Roman Britain.

See also

- Gaul

- Poitevin (language)

- Roman Republic

References

- Lafond 2006.

- Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 7:4:6

- Pliny. Naturalis Historia, 4:108

- Ptolemy. Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis, 2:7:5

- Ausonius. epist., 3:36

- Falileyev 2010, p. entry 3309.

- Nègre 1990, p. 156.

- Caesar, Commentarii de Bello Gallico iii.11.

- The c, in Poictou and Poictevin, was often retained into early modern times.

- Ptolemy, Geography ii.6.

Bibliography

- Cancik, Hubert; Schneider, Helmuth, eds. (2003), "Aquitania", Brill's New Pauly Encyclopedia of the Ancient World, II, Leiden: Brill Academic Publisher, ISBN 90-04-12259-1.

- Caesar, G. Julius (1990), "Gallic War I", in Lewis, Naphtali; Reinhold, Meyer (eds.), Roman Civilization: The Republic and the Augustan Age, I (3rd ed.), New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 216–219, ISBN 0-231-07131-0

- Crook, J.A.; Lintott, A.; Rawson, E., eds. (1970), The Cambridge Ancient History Set (The Cambridge Ancient History), IX (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-85073-8

- Falileyev, Alexander (2010). Dictionary of Continental Celtic Place-names: A Celtic Companion to the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. CMCS. ISBN 978-0955718236.

- Nègre, Ernest (1990). Toponymie générale de la France (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-02883-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony, eds. (2003), Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-866172-X

- Lafond, Yves (2006). "Pictones". Brill’s New Pauly.

- Osgood, Josiah (April 2007), "Caesar in Gaul and Rome: War in Words", American Historical Review, 112 (2): 559–560, doi:10.1086/ahr.112.2.559a.