Piano sonatas (Boulez)

Pierre Boulez composed three piano sonatas. The First Piano Sonata in 1946, a Second Piano Sonata in 1948, and a Third Piano Sonata was composed in 1955–57 with further elaborations up to at least 1963, though only two of its movements (and a fragment of another) have been published.

First Piano Sonata

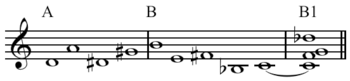

Boulez's First Piano Sonata, completed in 1946, has two movements. It was his first twelve-tone serial work (together with his Sonatine for flute and piano), and he originally intended to dedicate it to René Leibowitz, but their friendship ended when Leibowitz tried to make "corrections" to the score (Peyser 1999, 162, quoted without a page reference in Ruch 2004).

- Lent – Beaucoup plus allant (slow – moving along a lot more)

- Assez large – Rapide (quite broad – quick)

Second Piano Sonata

The Second Piano Sonata of 1947–48 is an original work which gained Boulez an international reputation. The pianist Yvette Grimaud gave the world premiere on 29 April 1950 (Nattiez 1993, 37). Through his friendship with the American composer John Cage, the work was performed in the U.S. by David Tudor in 1950 (Nattiez 1993, 77–79). The work is in four movements, lasting a total of about 30 minutes. It is notoriously difficult to play, and the pianist Yvonne Loriod "is said to have burst into tears when faced with the prospect" of performing it (Fanning n.d.). Tom Service listed it as one of ten key Boulez compositions (Service 2016).

- Extrêmement rapide (extremely fast)

- Lent (slow)

- Modéré, presque vif (moderate, almost lively)

- Vif (lively)

Third Piano Sonata

The Third Piano Sonata was first performed by the composer in Cologne and at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse in 1958, in a "preliminary version" of its five-movement form. A subsequent Darmstadt performance by the composer, on 30 August 1959 in the Kongresssaal Mathildenhöhe, was recorded and has been released commercially on CD2 of the seven-disc boxed set, Neos 11360, Darmstadt Aural Documents, Box 4: Pianists ([Germany]: Neos, 2016).

One motivating force for its composition was Boulez's desire to explore aleatoric music. He published several writings, both criticizing the practice and suggesting its reformation, leading up to the composition of this sonata in 1955–57/63. Boulez has published only two complete movements of this work (in 1963), and a fragment of another (in Universal Edition 1967), the other movements having been written up to various stages of elaboration but not completed to the composer's satisfaction. Of the unpublished movements (or "formants", as Boulez calls them), described in Edwards 1989, the one titled "Antiphonie" is the most fully developed. It has been analysed by Pascal Decroupet (2004, 152–59). The formant titled "Strophe" is the one least developed since the preliminary form but:

a 1958 radio tape of the composer's Cologne performance of the Third Piano Sonata shows that the wealth of cross-reference introduced by the inclusion of the other three movements, even in their preliminary versions, contributes exponentially to the complex, multiform effect of the whole. (Edwards 1989, 5–6)

A facsimile of the manuscript of the preliminary version of the remaining formant, "Séquence", was published in Schatz and Strobel 1977, but was subsequently continued to nearly twice its original length (Edwards 1989, 4).

- "Antiphonie" (unpublished except for a fragment, called "Sigle" [Siglum])

- "Trope"

- "Constellation" (published only in its retrograde version, as "Constellation-Miroir")

- "Strophe" (unpublished)

- "Séquence" (unpublished, except for a facsimile of the preliminary-version manuscript)

References

- Boulez, Pierre. 1986. Orientations. Faber and Faber. London. ISBN 0-571-14347-4.

- Cope, David. 2001. New Directions in Music, "An Interview with Pierre Boulez; February 1969". Prospect Heights, Illinois: Waveland Press, Inc.. pp. 30–32. ISBN 1-57755-108-7.

- Decroupet, Pascal. 2004. "Floating Hierarchies: Organisation and Composition in Works by Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen during the 1950s". In A Handbook to Twentieth-Century Musical Sketches, edited by Patricia Hall and Friedemann Sallis, 146–60. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Edwards, Allen. 1989. "Unpublished Bouleziana at the Paul Sacher Foundation". Tempo (New Series) no. 169 (June), pp. 4–15.

- Fanning, David. n.d. Stravinsky: Pétrouchka – Prokofiev: Sonate No. 7 – Webern: Variationen op. 27 – Boulez: Sonate No. 2, Maurizio Pollini, included booklet. Deutsche Grammophon 447 431–2, 1995.

- Harbinson, William G. 1989. "Performer Indeterminacy and Boulez's Third Sonata". Tempo (New Series) no. 169 (June), pp. 16–20.

- Leeuw, Ton de. 2005. Music of the Twentieth Century: A Study of Its Elements and Structure, translated from the Dutch by Stephen Taylor. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.ISBN 9053567658.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques. 1993. The Boulez-Cage Correspondence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48558-4.

- Peyser, Joan. 1999. To Boulez and Beyond: Music in Europe Since The Rite of Spring, foreword by Charles Wuorinen. New York: Billboard Books. ISBN 0-8230-7875-2. Revised edition, Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8108-5877-0 (pbk).

- Ruch, Allen B. 2004. "Pierre Boulez: Third Piano Sonata; Répons". themodernword.com .Archived 4 February 2013, from http://www.themodernword.com/joyce/music/boulez.html (accessed 25 January 2017)

- Schatz, Ingeborg, and Hilde Strobel (eds.). 1977. Heinrich Strobel „Verehrter Meister, lieber Freund“: Begegnungen mit Komponisten unserer Zeit. With photographs by Heinrich Strobel. Stuttgart and Zurich: Belser Verlag.

- Service, Tom. 2016. "Pierre Boulez: 10 Key Works, Selected by Tom Service". The Guardian (6 January; accessed 4 April 2020) ISSN 0261-3077.

- Universal Edition. 1967. UE Buch der Klaviermusik des 20. Jahrhunderts. Vienna: Universal Edition.

Further reading

- Decroupet, Pascal. 2012. "Le rôle des clés et algorithmes dans le décryptage analytique: L'exemple des musiques sérielles de Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen et Bernd Alois Zimmermann". Revue de Musicologie 98, no. 1:221–46.

- Losada, Catherine C. 2014. "Complex Multiplication, Structure, and Process: Harmony and Form in Boulez’s Structures II". Music Theory Spectrum 36, no. 1 (Spring): 86–120.