Piano Quintet (Schumann)

The Piano Quintet in E-flat major, Op. 44, by Robert Schumann was composed in 1842 and received its first public performance the following year. Noted for its "extroverted, exuberant" character, Schumann's piano quintet is considered one of his finest compositions and a major work of nineteenth-century chamber music.[1] Composed for piano and string quartet, the work revolutionized the instrumentation and musical character of the piano quintet and established it as a quintessentially Romantic genre.

Composition and performance

.png)

Schumann composed his piano quintet in just a few weeks in September and October 1842, in the course of his so-called "Chamber Music Year." Prior to 1842, Schumann had completed no chamber music at all with the exception of an early piano quartet (in 1829). However, during his year-long concentration on chamber music he composed three string quartets, Op. 41; followed by the piano quintet, Op. 44; a piano quartet, Op. 47; and the Phantasiestücke for piano trio, Op. 88.

Schumann began his career primarily as a composer for the keyboard, and after his detour into writing for string quartet, according to Joan Chisell, his "reunion with the piano" in composing a piano quintet gave "his creative imagination ... a new lease on life."[2]

John Daverio has argued that Schumann's piano quintet was influenced by Franz Schubert's Piano Trio No. 2 in E-flat major, a work Schumann admired. Both works are in the key of E-flat, feature a funeral march in the second movement, and conclude with finales that dramatically resurrect earlier thematic material.[3]

Schumann dedicated the piano quintet to his wife, the great pianist Clara Schumann. She was due to perform the piano part for the first private performance of the quintet on 6 December 1842. However, she fell ill and Felix Mendelssohn stepped in, sight-reading the "fiendish" piano part.[4] Mendelssohn's suggestions to Schumann after this performance led the composer to make revisions to the inner movements, including the addition of a second trio to the third movement.[4]

Clara Schumann did play the piano part at the first public performance of the piano quintet on 8 January 1843, at the Leipzig Gewandhaus. Clara pronounced the work "splendid, full of vigor and freshness."[4] She often performed the work throughout her life.[5] On one occasion, however, Robert Schumann asked a male pianist to replace Clara in a performance of the quintet, remarking that "a man understands that better."[5]

Instrumentation and genre

Schumann's piano quintet is scored for piano and string quartet (two violins, viola, and cello).

Schumann's choice to pair the piano with a standard string quartet lineup reflects the changing technical capabilities and cultural importance, respectively, of these instruments. By 1842, the string quartet had come to be regarded as the most significant and prestigious chamber music ensemble, while advances in the design of the piano had increased its power and dynamic range. Bringing the piano and string quartet together, Schumann's Piano Quintet takes full advantage of the expressive possibilities of these forces in combination, alternating conversational passages between the five instruments with concertante passages in which the combined forces of the strings are massed against the piano. At a time when chamber music was moving out of the salon and into public concert halls, Schumann reimagines the piano quintet as a musical genre "suspended between private and public spheres" alternating between "quasi-symphonic and more properly chamber-like elements."[6]

Analysis

The piece contains four movements in the standard fast-slow-scherzo-fast pattern:

- Allegro brillante

- In modo d'una marcia. Un poco largamente

- Scherzo: Molto vivace

- Allegro ma non troppo

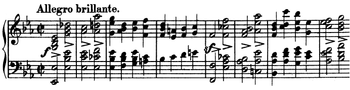

First movement: Allegro brillante

The tempo marking for the first movement is Allegro brillante. The Italian adjective brillante means "glittering" or "sparkling." The energetic main theme is characterized by wide, upward-leaping intervals. The contrasting second theme, marked dolce, is reached after a transitional section marked by glances at remoter flat keys. It is presented as a duet between cello and viola, and its "meltingly romantic"[4] character is typical of Schumann's ardent inspiration in this quintet. The central development consists largely of virtuoso figuration in the piano, based on a diminution of the third and fourth bars of the opening theme, which modulates between two vigorous statements of the latter in A-flat and F minor. The figuration is transposed down a tone more or less exactly on its second appearance to lead back to the tonic key. After a standard recapitulation of the main themes a short, energetic coda rounds off the movement. While Schumann is frequently criticized for his discursive, repetitive approach to sonata form, he largely succeeds in keeping this opening Allegro compactly organized and not excessively long.

Second movement: In modo d'una marcia. Un poco largamente

The main theme of this movement is a funeral march in C minor. It alternates with two contrasting episodes, one a lyrical theme (B) carried by the first violin and cello, the second (C), Agitato, carried by the piano with string accompaniment, which is a transformation of the principal theme disguised by changes in rhythm and tempo. The whole forms a seven-part rondo: A (C minor)--B (C major)--A (C minor)--C (variant of A, F minor)--A' (C minor)--B' (F major)--A (C minor).

The transition between the funeral march and the second (agitated) episode reuses the descending octaves in the piano (doubled by violin) from the second ending of the first movement exposition (see figure). This is one of several moments in the quintet where Schumann creates unity across movements by subtly reusing thematic material. A, the funeral march, is varied on its return after the agitato section with rapid triplets in the piano and counterpoint reminiscent of the previous episode in first violin and cello, while the second appearance of B in F major also is with an enriched piano accompaniment.

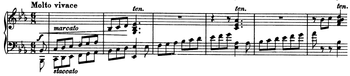

Third movement: Scherzo: Molto vivace

The main section of this lively movement is built almost entirely on ascending and descending scales. There are two trios. Trio I, in G-flat major, is a lyrical canon for violin and viola. Trio II, added at the suggestion of Mendelssohn, is a heavily accented moto perpetuo whose 2/4 meter and restlessly modulating, mostly minor tonality are in sharp contrast to the 6/8 and relative stability of the rest. After the third and final appearance of the Scherzo a brief coda based on the scales concludes the movement, slipping in a recall of Trio I in the final bars.

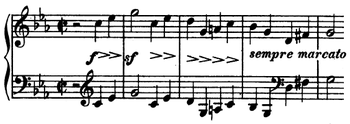

Finale: Allegro ma non troppo

The finale begins in G minor, on a C minor chord, rather than in the tonic. The movement as a whole is cast in an unusual form that partly reflects, but ultimately triumphs over Schumann's frequent difficulties with the conventional sonata form in his larger-scale instrumental movements. The original handling of both form and key contrasts sharply with the largely conventional formal organization of the previous three movements.

A summary of the main themes and key areas follows:

Bar 1: G minor theme A1

Bar 21: E-flat major theme A2

Bar 29: D minor A1

Bar 37: B-flat major A2

Bar 43: G major theme B (with an important motive B’, first introduced by the viola in 54). B itself is a diminished version of A2.

Bar 77: B minor-major A1

Bar 114: E major-G-sharp minor theme C (accompanied by B’)

****

Bar 136: G-sharp minor A1

Bar 148: D-sharp minor A1

Bar 156: B major A2

Bar 164: B-flat minor A1

Bar 172: G-flat major A2

Bar 178: E-flat major B recapitulated

****

Bar 212: G minor A1

Bar 224: E-flat major theme D

Bar 248: fugato on A1

Bar 274: E-flat major C (B’) recapitulated

Bar 319: E-flat major, fugato on A1 combined with the opening theme of the first movement, Allegro brillante

Bar 378: E-flat major D recapitulated

Bar 402: Coda

The main themes, A1, A2, B and C, are all introduced in the first 135 bars, making this opening roughly equivalent to a sonata exposition. The tonic key, however, is almost entirely absent, with the music mostly remaining in G minor/major until the introduction of the lyrical theme C in the remote key of E major at bar 114. The music modulates to G-sharp minor to begin what is essentially a recapitulation in bar 136, with B returning in E-flat to finally establish the true tonic in bar 178, very late in a lengthy movement. More than 200 bars remain to unfold, however, almost entirely in the tonic. During their course, Schumann introduces yet another theme, the syncopated D, gets around to recapitulating the lyrical theme C in the tonic, and develops the music further via two fugato passages, the second unexpectedly and impressively incorporating the principal theme of the opening Allegro brillante and combining it with the opening theme A1, finally heard in the tonic. This coup may have been inspired by a similar confluence of themes in the E flat quartet op. 12 of Felix Mendelssohn.[7] It also, probably deliberately, evokes the climactic contrapuntal finales of works such as Mozart's Jupiter symphony. The movement as a whole can be noted for the rondo-like reappearances of the opening theme A1, which consistently avoids the tonic key until the final fugato; for its innovative key scheme, which combines the restless modulations of a traditional sonata development with the idea of recapitulation in the tonic; and for its successful integration of counterpoint within a non-contrapuntal formal structure.

Reception and influence

Schumann's piano quintet was widely acclaimed and much imitated.[8] Its success firmly established the piano quintet as a significant, and quintessentially Romantic, chamber music genre.[9] The Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34 of Johannes Brahms, reworked from an earlier sonata for two pianos (itself a reworking of an earlier string quintet) at the urging of Clara Schumann, was one of many significant Romantic piano quintets that show Schumann's influence and adopt his choice of instrumentation.

Schumann's Piano Quintet failed to please at least one discriminating listener: Franz Liszt heard the piece performed at Schumann's home and dismissed it as "too Leipzigerisch," a reference to the conservative music of composers from Leipzig, especially Felix Mendelssohn.

Use in later art and music

The funeral march theme of the second movement is prominently used as the main theme of the film Fanny and Alexander by Ingmar Bergman, and is played on violin by Rutger Hauer's character Lothos while Buffy kills the vampire portrayed by Paul Reubens in the 1992 feature Buffy the Vampire Slayer. It is also featured prominently on the all-classical soundtrack of the noted 1934 horror film The Black Cat. It is used several times in Yorgos Lanthimos' 2018 period piece The Favourite.

References

- Daverio, John. “'Beautiful and Abstruse Conversations': The Chamber Music of Schumann.” Nineteenth-Century Chamber Music. Ed. Stephen E. Hefling. 1998, Schirmer, p. 220

- Chisell, Joan. "Robert Schumann" in Alec Robertson, ed. Chamber music (1963, Penguin), p. 184

- Daverio, John (2002). Crossing Paths: Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 13-46.

- Potter, Tully. Liner notes. SCHUMANN: Piano Quintet, Op. 44 / BRAHMS: Piano Quartet No. 2 (Curzon, Budapest Quartet) (1951-1952)

- Reich, Nancy (2001). Clara Schumann: The Artist and the Woman. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 115, 231.

- Daverio, John. Robert Schumann: Herald of a "New Poetic Age." (1997, Oxford), p. 256

- Chissell (1979), 159-160.

- Smallman, Basil. The Piano Quartet and Quintet: Style, Structure, and Scoring, p. 53.

- Stowell, Robin. The Cambridge Companion to the String Quartet, p. 324.

Bibliography

- Schumann's Piano Quintet was first published in 1843. It was republished by Breitkopf and Hartel in Robert Schumann's Werke Serie V (1881).

- Berger, Melvin. "Guide to Chamber Music", Dover, 2001, 404-405.

- Chisell, Joan (1979). Schumann. London: J. M. Dent and Sons. ISBN 9780460125888.

- Daverio, John (2002). Crossing Paths: Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Daverio, John. Robert Schumann: Herald of a "New Poetic Age." (1997, Oxford)

- Daverio, John. “'Beautiful and Abstruse Conversations': The Chamber Music of Schumann.” Nineteenth-Century Chamber Music. Ed. Stephen E. Hefling. New York: Schirmer, 1998: 208–41.

- Nelson, J.C. ‘Progressive Tonality in the Finale of the Piano Quintet, op.44 of Robert Schumann’. Indiana Theory Review, xiii/1 (1992): 41–51.

- Potter, Tully. Liner notes. SCHUMANN: Piano Quintet, Op. 44 / BRAHMS: Piano Quartet No. 2 (Curzon, Budapest Quartet) (1951-1952)

- Reich, Nancy (2001). Clara Schumann: The Artist and the Woman. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Smallman, Basil. The Piano Quartet and Quintet: Style, Structure, and Scoring.

- Stowell, Robin. The Cambridge Companion to the String Quartet.

- Wollenberg, Susan. ‘Schumann's Piano Quintet in E flat: the Bach Legacy’, The Music Review, lii (1991): 299–305.

- Westrup, J. ‘The Sketch for Schumann's Piano Quintet op.44’, Convivium musicorum: Festschrift Wolfgang Boetticher. Ed. H. Hüschen and D.-R. Moser. Berlin, 1974: 367–71.

- Tovey, D.F. Essays in Musical Analysis: Chamber Music. London: Oxford, 1944: 149–54.

External links

- Piano Quintet, Op.44: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- 1942 Performance of the Piano Quintet by the Busch Quartet and Rudolf Serkin

- Performance of the Piano Quintet by the Steans Artists of Musicians from Ravinia from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in MP3 format

- June 8, 2010 performance of the Piano Quintet at the Montreal Chamber Music Festival