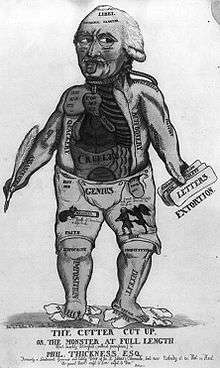

Philip Thicknesse

Captain Philip Thicknesse (1719 – 23 November 1792) was an English author, eccentric, and friend of the artist Thomas Gainsborough.[1]

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

Early life

Philip Thicknesse was born in Staffordshire, England, son of John Thicknesse, Rector of Farthinghoe, Northamptonshire and Joyce (née Blencowe) Thicknesse. He was brought up in Farthinghoe.

Career

Thicknesse visited the Colony of Georgia in September 1736, but returned to England in 1737, claiming to be the first of the emigrants to return.[2] He obtained a commission as a Captain of an independent company in Jamaica after 1737, and on an expedition against Jamaican Maroons in the Blue Mountains, he wrote in his autobiography of encounters with Windward Maroon leaders Quao and Queen Nanny. He transferred to a marine regiment as a Captain-Lieutenant in 1740. He was Lieutenant-Governor of Landguard Fort, Suffolk (1753–1766).

Thicknesse was a friend of the society artist Thomas Gainsborough, whom he met in about 1753,[3] and of his less well-known brother, the inventor Humphrey Gainsborough. He was an author and wrote for The Gentleman's Magazine. He also published The Speaking Figure and the Automaton Chess Player, Exposed and Detected, a not entirely accurate exposé of the chess-playing machine The Turk.

In 1742, Thicknesse eloped with Maria Lanove, a wealthy heiress, having abducted her from a street in Southampton and taken up residence in Bath, taking full advantage of the social whirl. In 1749 Maria and his children (by then three) contracted diphtheria. She and two children died, leaving only a daughter, Anna. When Maria's parents died some time later (his mother-in-law committing suicide), he spent much time trying to claim their fortune. Thicknesse then married Lady Elizabeth Tuchet, daughter of James Tuchet, 6th Earl of Castlehaven and Hon. Elizabeth Arundell, on 10 May 1749. They had a son George (1758-1818), later 19th Baron Audley. Elizabeth died in childbirth in 1762.

His third wife was his late wife's companion, Anne Ford (1732–1824), daughter of Thomas Ford, whom he married on 27 September 1762. Ann was a gifted musician with a beautiful voice, who was well-educated and knew five languages. She gave Sunday concerts at her father's house, but her ambition was to become a professional actress, and in spite of her father's disapproval, she left home to go on the stage. They had a son, Captain John Thicknesse RN (c1763–1846). The couple spent much time travelling in Europe. In later life he lived in the Royal Crescent, Bath,[4] in a house he let out and then sold. He moved to another, St Catherine's Hermitage, and landscaped the grounds to create his own "hermit's cell".[5][6][7]

Death

Thicknesse died on a journey near Boulogne, Pas-de-Calais, France, and was buried there. In his later life he had become an "ornamental hermit".

His will stipulated that his right hand be cut off and delivered to his son, George, who was inattentive, "to remind him of his duty to God after having so long abandoned the duty he owed to a father, who once so affectionately loved him."[8]

Books

- 1768: Useful Hints to those who Make the Tour of France. This gains a mention from a character in Tobias Smollett's epistolary novel The Expedition of Humphry Clinker.[9]

- 1772: A Treatise On The Art Of Decyphering, And Of Writing In Cyphers,With An Harmonic Alphabet

- 1777: A Year's Journey through France and Part of Spain. 2 vols. Bath: printed by R. Cruttwell, for the author; and sold by Wm. Brown, London

- 1778: The New Prose Bath Guide : for the year 1778. [London?]: Printed for the author: and sold by Dodsley

- 1786: A Year's Journey Through The Pais Bas: or, Austrian Netherlands. London, printed for J. Debrett

- 1788: Memoirs and Anecdotes of Philip Thicknesse, Late Lieutenant-Governor of Land Guard Fort, and unfortunately Father to George Touchet, Baron Audley. [London?]: printed for the Author, MDCCLXXXVIII. [1788]. A third volume was published in 1791.

References

- Katherine Turner, Thicknesse, Philip (1719–1792), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004. Online edition, accessed 12 January 2008.

- Turner, Katherine (2017). "'Ill-Designing People': Revisiting Philip Thicknesse's Recollections of Georgia". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 101 (3): 234–262. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Hayes, John. (1980) Thomas Gainsborough. London: Tate Gallery. p. 20. ISBN 0905005724

- Lowndes, William (1981). The Royal Crescent in Bath. Redcliffe Press. ISBN 978-0-905459-34-9.

- Raffael, Michael (2006). Bath Curiosities. Birlinn. p. 56. ISBN 978-1841585031.

- Thicknesse, Philip (1787). A sketch of St. Catherine's hermitage, near Bath; in a letter to Sir John O'Carroll, Bart. at Brussels. R. Cruttwell.

- "Hermitage, The, St Catherine's, England". Park sand Gardens UK. Parks and Gardens Data Services Ltd. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Michael Olmert (1996), Milton's Teeth and Ovid's Umbrella: Curiouser & Curiouser Adventures in History, p. 72. Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 0-684-80164-7.

- OUP World's Classics edition, 1984, p.

External links

- Works by Philip Thicknesse at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Philip Thicknesse at Internet Archive

- Biography

- Pictures in the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Manybooks.net entry

- Portrait of his wife nee Ann Ford