Phidippus californicus

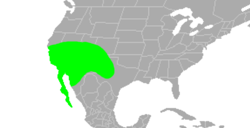

Phidippus californicus is a species of jumping spider. It is found in the southwestern United States (California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Texas, Utah) and northern Mexico (Baja California peninsula, and Sonora).

| Phidippus californicus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. californicus |

| Binomial name | |

| Phidippus californicus Peckham & Peckham, 1901 | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Habitat

P. californicus occurs in the sagebrush community of the Great Basin Desert. These large jumping spiders are found on bushes such as the sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), the rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus nauseosus), and the Four-winged Saltbrush (Atriplex canescens). P. californicus prefers bushes that grow on slopes with thin, stony soils, and appears to avoid conifers and moist habitats (e.g., the proximity of irrigation ditches). In the same habitat, often on the same bush, two other Phidippus species are found: P. apacheanus and P. octopunctatus.[1]

Description

Females can reach 12 mm body length, males 7 to 11 mm. Both sexes have blue-green iridescent chelicerae, a black cephalothorax and limbs, and a bright red abdomen with a median black stripe (similar to the female P. johnsoni). Between the black and red areas on the posterior part of the dorsal abdomen there are two minute white spots. At the sides of the abdomen there are light diagonal bands, and there is also a light transverse anterior band on the dorsum. These markings vary in conspicuousness: the bands and spots may be only a somewhat lighter shade of red than the remainder of the abdomen, while the median black stripe may be so reduced in width and length that the abdomen appears solid red. Sometimes, the basic color is orange rather than red, and very old spiders may even be yellow. In this species, the adult males and the adult females are similar in coloration, and this is also true of P. apacheanus. It is more usual for the males of Phidippus to have iridescent chelicerae and a distinctive adult coloration while the females of this genus remain similar to the immature spiders (e.g., P. clarus, P. octopunctatus, P. whitmani).

It is one of the species of jumping spiders which are mimics of mutillid wasps in the genus Dasymutilla (commonly known as "velvet ants"); several species of these wasps are similar in size and coloration, and possess a very painful sting.

From the second instar on, the spiderlings have a brownish-gray cephaIothorax and limbs, and a red abdomen with markings limited to the posterior portion. These consist of a pair of black stripes, each bearing two conspicuous white dots, separated by a light region. The light region may be gray, white, or even golden; immediately anterior to the black stripes it is enlarged into a conspicuous light dot. While the abdomen of very young spiderlings appears bronze, the red color of the abdomen is striking in later instars. In one of the later instars, the 5th or perhaps the 6th, a red cap appears in the eye region, but this marking disappears in the following molt. The light basal band and side bands of the adult are also present in immature spiders, and, in the two instars proceeding maturity, the chelicerae are also iridescent.[1]

Behavior

P. californicus is active from mid-morning until dusk, and can be seen in bushes running along branches or poised near their tips. Running is interrupted frequently: the spider stops, turns to one side and then the other, apparently scanning its surroundings.

It builds a retreat, consisting of a slightly flattened tube of silk, surrounded by guy-lines that attach it to the twigs or leaves of the bush. Molting and breeding nests are similar, but use much more silk. These are found under stones at the base of the bush.

When a male and an unmated female meet, it takes about 30–60 seconds of courtship until mating occurs. Males have been observed to initially court females laden with eggs, females from different Phidippus species, or even simples models out of clay with a pair of wires as appendages. Previously mated females may retreat, or attack the male as prey.[1]

Courtship

Male courtship display is similar to that of P. apacheanus, P. clarus, or P. octopunctatus. The male begins his display by holding the carapace very high, shifting the abdomen to one side, and raising the first pair of legs. In this position, he moves before the female, stopping after each few steps. The male advances in a zig-zag pathway, shifting his abdomen to the other side at the end of each oblique approach. Throughout, the dancing male flicks his forelegs up and down, holding them wide apart at first and bringing them closer and closer together as he nears the female. Then, with forelegs held almost parallel before him, he touches the female cautiously once or twice. If the female remains still at this stage, the male climbs over her, and uses the forelegs to help turn her abdomen to the side. When the genital pore, which lies on the ventral abdomen, is thus exposed, the male inserts his palpus. After 2-3 min., the male withdraws this pedipalp, turns the female's abdomen in the other direction, and inserts the other pedipalp.[1]

Raising the forelegs and holding the abdomen to one side are by no means specific to courtship. This display occurs to a wide variety of objects that are approaching too close to the spider: other spiders - regardless of sex, houseflies or other large prey, models of prey that are about the size of the spider, such as 9–12 mm spheres, or even the end of a finger or a pencil. In these situations, however, the spider with its forelegs raised and waving backs off while facing the moving object and, when 5–8 cm away, turns away and flees.[1]

In intraspecific encounters, the effect of raising the forelegs is to bring the other spider to an abrupt halt, whether it be a wandering conspecific, a courting male preparing to touch the female, or a female stalking or about to jump at the male. Indeed, raising of the forelegs appears to have this 'stop-sign' effect even in encounters between congenerics of the three Phidippus species. Drees,[2] working with female Salticus scenicus, was able to initiate hunting behavior by moving a black dot along a white wall, and to stop the pursuing spider by moving wires projecting from the side of the model through an angle that imitated the waving of the forelegs.[1]

Female P. californicus and P. apacheanus are unusual in that they perform an acceptance dance just before the male touches them. With forelegs high and wide apart and abdomen bent to the side, the female sways before the male, sometimes with a few steps to one side and then the other. In other Phidippus species, the female rejects the male by extending the first pair of legs whenever he approaches too closely, and merely fails to ward him off when she is ready to accept him.[1]

Hunting

The spider seldom initiates hunting behavior to still prey, and interrupts ongoing hunting behavior when the prey ceases to move. When pursuing a prey, it at first moves rapidly, slowing down as it comes near the prey. Within 5 centimetres (2.0 in) of the prey, it presses its body close to the ground and draws the legs in toward the body. At about 1.5 centimetres (0.59 in), it becomes still in this crouched position, attaches a safety thread to the ground, and jumps at the prey. When attacking large prey, it may take a curved course in order to jump on it from behind.[1]

Immature males require about half an hour to digest a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), while individuals 1 centimetre (0.39 in) long need less than 9 minutes. To consume a house fly (Musca domestica), even large adult females need almost one hour. The hungrier a spider, the longer will it take to digest the prey. If hungry, they will readily capture more than one prey at a time, if it comes very near. Satiated spiders will respond to prey by extending the forelegs towards it.[1]

Reproduction

Adult males are found from early April to July, females from early May to July. The female lays two to three successive batches of eggs, with each batch containing fewer eggs. About 40 hatch from the first, 30 from the second, and few, if at all, from the third. The spiderlings hatch after about three weeks. They remain inside the nest until after a first molt, a little more than two weeks later, at which time they are self-sufficient.[1]

Footnotes

- Gardner 1965

- Drees 1952

References

- Drees, O. (1952): Untersuchungen über die angeborenen Verhaltensweisen bei Springspinnen (Salticidae). Z. Tierpsychol. 9: 167-207.

- Gardner, B.T. (1965): Observations on Three Species of Phidippus Jumping Spiders (Araneae: Salticidae). Psyche 72:133-147. PDF (P. californicus = P. coccineus, P. apacheanus, P. octopunctatus = P. opifex)