Phalaris

Phalaris (Greek: Φάλαρις) was the tyrant of Akragas (now Agrigento) in Sicily, from approximately 570 to 554 BC.

History

Phalaris was entrusted with the building of the temple of Zeus Atabyrius in the citadel and took advantage of his position to make himself despot.[1] Under his rule, Agrigentum seemed to have attained considerable prosperity. He supplied the city with water, adorned it with fine buildings, and strengthened it with walls. On the northern coast of the island, the people of Himera elected him general with absolute power, in spite of the warnings of the poet Stesichorus.[2] According to the Suda he succeeded in making himself master of the whole of the island. He was at last overthrown in a general uprising headed by Telemachus, the ancestor of Theron of Acragas (tyrant c. 488–472 BC), and burned in his own brazen bull.

Phalaris was renowned for his excessive cruelty. Among his alleged atrocities is cannibalism: he was said to have eaten suckling babies.[3]

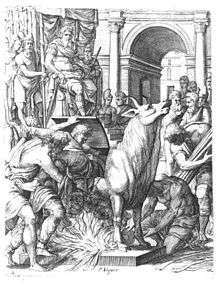

In his Brazen bull, said to have been invented by Perillos of Athens, the tyrant's victims were shut in and roasted alive by a fire kindled beneath while their shrieks represented the bellowing of the bull. Some scholars of the early 20th century proposed a connection between Phalaris' bull and the bull-images of Phoenician cults (cf. the Biblical golden calf), and hypothesized a continuation of Eastern human sacrifice practices. This idea has subsequently fallen out of favor.

Pindar, who lived less than a century afterwards, expressly associates this instrument of torture with the name of the tyrant.[4]

There was certainly a brazen bull at Agrigentum that was carried off by the Carthaginians to Carthage. This is said to have been later taken by Scipio the Elder and restored to Agrigentum circa 200 BC. However, it is more likely that it was Scipio the Younger who returned this bull and other stolen works of art to the original Sicilian cities, after his total destruction of Carthage circa 146 BC, which ended the Third Punic War.

Literary rehabilitation

Some four centuries after his death, Phalaris was the object of a literary reinvention whereby he came to be seen as a humane leader who was a patron of philosophy and literature. This new reputation was due to a paradoxical defence of his character attributed to Lucian,[5] and to his supposed authorship of an epistolary corpus.[6] In 1699, Richard Bentley published a famous Dissertation on the Epistles of Phalaris in which he proved the spuriousness of the epistles.[7]

References

- Aristotle, Politics, v. 10

- Aristotle, Rhetoric, ii. 20

- Tatian. "Tatian's Address to the Greeks", Chapter XXXIV.

- Pindar, Pythian 1

- Lucian's original text at Perseus.

- A digitised 1706 translation of the Epistles at archive.org.

- Text at archive.org.

Sources

External links

- Livius, Phalaris of Acragas by Jona Lendering

- Phalaris in the Dictionary of Greek & Roman Biography & Mythology, ed. Wm. Smith

- Phalaris I & Phalaris II by Lucian at Lucian of Samosata Project

- Phalaris - The Source Material - References by ancient authors