Macedonian phalanx

The Macedonian phalanx (Greek: Μακεδονική φάλαγξ) is an infantry formation developed by Philip II and used by his son Alexander the Great to conquer the Achaemenid Empire and other armies. Phalanxes remained dominant on battlefields throughout the Ancient Macedonian Period, although wars had developed into more protracted operations generally involving sieges and naval combat as much as pitched battles, until they were ultimately displaced by the Roman legions.

Development

In 359 BC following the Macedonian defeat from the Illyrians which killed the majority of Macedonia's army and the current King Perdiccas III, Perdiccas' brother Philip II took the throne.[1] Philip II was a hostage in Thebes for much of his youth (367-360), where he witnessed the combat tactics of the general Epaminondas, which then influenced his restructuring of the infantry.[2] Philip's military reforms were a new approach to the current hoplite warfare which focused on their shield, the hoplon; his focus was on a new weapon, the sarissa.[1] The first phalanx was a 10 by 10 square with very few experienced troops.[1] The phalanx was later changed to a 16 by 16 formation, and while the date for this change is still unknown, it occurred before 331 under Philip’s rule.[2] Philip called the soldiers in the phalanx pezhetairoi, meaning "foot-companions", bolstering the importance of the phalanx to the king.[3] Philip also increased the amount of training required for the infantry and introduced regulations on military behaviour.[3] During Alexander's campaign, the phalanx remained more or less the same, with the notable difference being more non-Macedonian soldiers among the ranks.[2]

Equipment

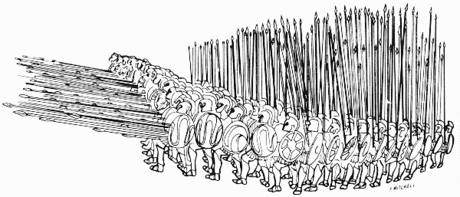

Each phalangite carried as his primary weapon a sarissa, a double-pointed pike over 6 m (18 ft) in length, weighing about 6.6kg (14.5 pounds). The sarissae were carried in two pieces before a battle and then slid together when they were being used.[4] At close range such large weapons were of little use, but an intact phalanx could easily keep its enemies at a distance. The weapons of the first five rows of men all projected beyond the front of the formation, so that there were more spear points than available targets at any given time.[4] Men in rows behind the initial five angled their spears at a 45 degree angle in an attempt to ward off arrows or other projectiles.[5] The secondary weapon was a shortsword called a xiphos.[1] The phalangites also had a smaller and flatter shield than that of the Greek hoplon, measuring about 24 inches and weighing about 12 pounds.[4] The shield was made of bronze plated wood and was worn hung around the neck so as to free up both hands to wield the sarissa.[4] All of the armor and weaponry a phalangite would carry totaled about 40 pounds, which was close to 10 pounds less than the weight of Greek hoplite equipment.[1]

Formation

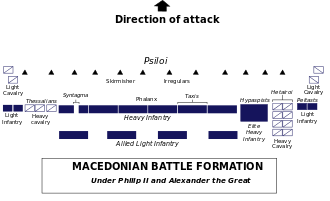

The phalanx consisted of a line-up of several battalion blocks called syntagmata, each of its 16 files (lochoi) numbering 16 men, for a total of 256 in each unit.[2] Each syntagma was commanded by a syntagmatarch, who – together with his subordinate officers – would form the first row of each block.[6]

Each file was led and commanded by a dekadarch who were the most experienced Macedonian soldiers and received about triple pay.[1] The leader was followed by another two experienced Macedonian soldiers, with a third positioned at the very end of the file, all three who received about double pay.[2] The rest of the file was filled up by more inexperienced soldiers, often Persians during Alexanders Campaign.[2] The phalanx was divided into taxis based on geographical recruitment differences.[2]

The phalanx used the "oblique line with refused left" arrangement, designed to force enemies to engage with soldiers on the furthest right end, increasing the risk of opening a gap in their lines for the cavalry to break through.[3] Due to the structure of the phalanx, it was weakest in the rear and on the right.

Neither Philip nor Alexander actually used the phalanx as their arm of choice, but instead used it to hold the enemy in place while their heavy cavalry broke through their ranks. The Macedonian cavalry fought in wedge formation[2] and was almost always stationed on the far right. The hypaspists, elite infantrymen who served as the king's bodyguard,[7] were stationed on the immediate right of the phalanx wielding hoplite sized spears and shields.[4] The left flank was generally covered by allied cavalry supplied by the Thessalians, which fought in rhomboid formation and served mainly in a defensive role.[2] Other forces—skirmishers, range troops, reserves of allied hoplites, archers, and artillery—were also employed.

Key battles

- Battle of Crocus Field (353/352)

- Battle of Chaeronea (338)

- Battle of the Granicus (334)

- Battle of Issus (333)

- Battle of Gaugamela (331)

- Battle of the Hydaspes (326)

References

- Gabriel, Richard A. (2010). Philip II of Macedonia: Greater Than Alexander. Washington, DC : Potomac Books. pp. 62–72. ISBN 9781597975681.

- Connolly, Peter (2012). Greece and Rome at War. Havertown: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 9781848326095.

- Brice, Lee L. (2012). Greek warfare from the Battle of Marathon to the conquests of Alexander the Great. California: ABC-CLIO, LLC. pp. 145–150. ISBN 9781610690706.

- Markle, Minor M. (July 1977). "The Macedonian Sarissa, Spear, and Related Armor". American Journal of Archaeology. 81 (3): 323–339. doi:10.2307/503007. JSTOR 503007.

- Polybius. The Histories. Chapters 28–32. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- Connolly, Peter: The Greek Armies, pp. 58-59: "The Macedonian Phalanx". MacDonald & Co. Ltd, London, 1982. ISBN 0 356 05580 9.

- Arrian, author. The campaigns of Alexander. ISBN 978-1-5077-6741-2. OCLC 1004422169.