Petrus Apianus

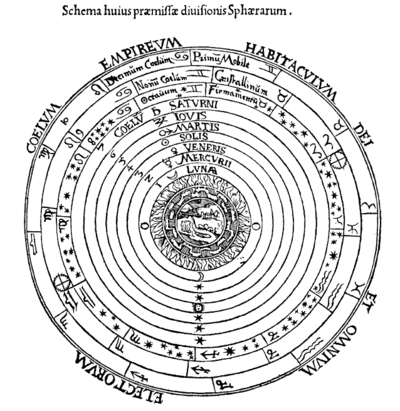

Petrus Apianus (April 16, 1495 – April 21, 1552),[1] also known as Peter Apian, Peter Bennewitz, and Peter Bienewitz, was a German humanist, known for his works in mathematics, astronomy and cartography.[2] His work on "cosmography", the field that dealt with the earth and its position in the universe, was presented in his most famous publications, Astronomicum Caesareum (1540) and Cosmographicus liber (1524. His books were extremely influential in his time, with the numerous editions in multiple languages being published until 1609. The lunar crater Apianus and asteroid 19139 Apian are named in his honour.[2]

Life and work

Apianus was born as Peter Bienewitz (or Bennewitz) in Leisnig in Saxony; his father, Martin, was a shoemaker. The family was relatively well off, belonging to the middle-class citizenry of Leisnig. Apianus was educated at the Latin school in Rochlitz. From 1516 to 1519 he studied at the University of Leipzig; during this time, he Latinized his name to Apianus (lat. apis means "bee"; "Biene" is the German word for bee).

In 1519, Apianus moved to Vienna and continued his studies at the University of Vienna, which was considered one of the leading universities in geography and mathematics at the time and where Georg Tannstetter taught. When the plague broke out in Vienna in 1521, he completed his studies with a BA and moved to Regensburg and then to Landshut. At Landshut, he produced his Cosmographicus liber (1524), a highly respected work on astronomy and navigation which was to see at least 30 reprints in 14 languages and that remained popular until the end of the 16th century. Later editions were produced by Gemma Frisius.[3]

In 1527, Peter Apianus was called to the University of Ingolstadt as a mathematician and printer. His print shop started small. Among the first books he printed were the writings of Johann Eck, Martin Luther's antagonist. This print shop was active between 1543 and 1540 and became well known for its high-quality editions of geographic and cartographic works. It is thought that he used stereotype printing techniques on woodblocks.[6] The printer's logo included the motto Industria superat vires in Greek, Hebrew, and Latin around the figure of a boy.[7]

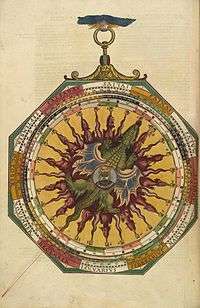

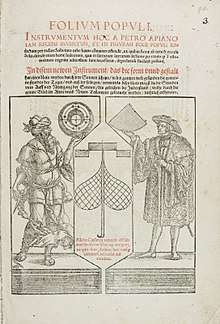

Through his work, Apianus became a favourite of emperor Charles V, who had praised Cosmographicus liber at the Imperial Diet of 1530 and granted him a printing monopoly in 1532 and 1534. In 1535, the emperor made Apianus an armiger, i.e. granted him the right to display a coat of arms. In 1540, Apianus printed the Astronomicum Caesareum, dedicated to Charles V. Charles promised him a truly royal sum (3,000 golden guilders),[lower-alpha 1] appointed him his court mathematician, and made him a Reichsritter (a Free Imperial Knight) and in 1544 even an Imperial Count Palatine. All this furthered Apianus's reputation as an eminent scientist. Astronomicum Caesareum is noted for its visual appeal. Printed and bound decoratively, with about 100 known copies,[9] it included several Volvelles that allowed users to calculate dates, the positions of constellations and so on.[10][11][12] Apianus noted that it took a month to produce some of the plates. Thirty-five octagonal paper cut instruments were included with woodcuts that are thought to have been made by Hans Brosamer (c. 1495 – 1555) who may have trained under Lucas Cranach, Sr. in Wittemberg.[13] It also incorporated star and constellation names from the work of the Arab astronomer Azophi (Abu al-Husain al-Sufi AD 903–986).[14] Apianus is also remembered for publishing the only known depiction of the Bedouin constellations in 1533. On this map Ursa Minor is an old woman and three maidens, Draco is four camels and Cepheus was illustrated as a shepherd with sheep and dog.[15]

Despite many calls from other universities, including Leipzig, Padua, Tübingen, and Vienna, Apianus remained in Ingolstadt until his death. Although he neglected his teaching duties, the university evidently was proud to host such an esteemed scientist. Apianus's work included in mathematics—in 1527 he published a variation of Pascal's triangle, and in 1534 a table of sines— as well as astronomy. In 1531, he observed Halley's Comet and noted that a comet's tail always point away from the sun.[16] Girolamo Fracastoro also detected this in 1531, but Apianus's publication was the first to also include graphics. He designed sundials, published manuals for astronomical instruments and crafted volvelles ("Apian wheels"), measuring instruments useful for calculating time and distance for astronomical and astrological applications.[17][18]

Apianus married the daughter of a councilman of Landshut, Katharina Mosner, in 1526. They would have fourteen children together, five girls and nine sons, one of whom was Philipp Apian (1531–1589), who, in addition to his own research, preserved the legacy of his father.[19]

Selected works

- Cosmographicus liber (also called Cosmographia), Landshut 1524.

- Ein newe und wolgegründete underweisung aller Kauffmanns Rechnung in dreyen Büchern, mit schönen Regeln und fragstücken begriffen, Ingolstadt 1527. A handbook of commercial arithmetic; depicted in the painting The Ambassadors by Hans Holbein the Younger.

- Cosmographiae introductio, cum quibusdam Geometriae ac Astronomiae principiis ad eam rem necessariis, Ingolstadt 1529.[20]:4

- Ein kurtzer bericht der Observation unnd urtels des jüngst erschinnen Cometen..., Ingolstadt 1532. On his comet observations.

- Quadrans Apiani astronomicus, Ingolstadt 1532. On quadrants.[20]:90

- Horoscopion Apiani..., Ingolstadt 1533. On sundials.[20]:91

- Instrument Buch..., Ingolstadt 1533. A scientific book on astronomical instruments in German.[20]:97

- Instrumentum primi mobilis, Nuremberg 1534. On trigonometry, contains sine tables.[20]:103

- Astronomicum Caesareum, Ingolstadt 1540.

Footnotes

- Whether Apian ever received the promised money is uncertain; in any case he wrote a letter to the emperor in 1549 asking him to finally pay the promised sum.[8]

References

- Kish (1970)

- "19139 Apian (1989 GJ8)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Broecke, Steven Vanden (2006). "The Use of Visual Media in Renaissance Cosmography: The Cosmography of Peter Apian and Gemma Frisius". Paedagogica Historica. 36: 130–150. doi:10.1080/0030923000360107.

- Keuning, Johannes (2008). "The history of geographical map projections until 1600". Imago Mundi. 12: 1–24. doi:10.1080/03085695508592085.

- Kish, George (2008). "The cosmographic heart: Cordiform maps of the 16th century". Imago Mundi. 19: 13–21. doi:10.1080/03085696508592261.

- Woodward, David (2008). "Some evidence for the use of stereotyping on Peter Apian's world map of 1530". Imago Mundi. 24: 43–48. doi:10.1080/03085697008592348.

- Johnson, A. F. (1965-06-01). "Devices of German Printers, 1501–1540". The Library. s5-XX (2): 81–107. doi:10.1093/library/s5-xx.2.81. ISSN 0024-2160.

- "APIAN, Peter (ursprünglich Bienewitz oder Bennewitz)". Bautz.de. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- Gingerich, Owen (2016). "Apianus's Astronomicum Caesareum and its Leipzig Facsimile". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 2 (3): 168–177. doi:10.1177/002182867100200303.

- Gislén, Lars (2017). "Apinanus' latitude volvelles – how were they made?". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 20: 13–20.

- Stebbins, F. A. (1959). "A Sixteenth-Century Planetarium". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 53: 197–203. Bibcode:1959JRASC..53..197S.

- Apian, Peter; Ionides, S. A. (1 January 1936). "Caesars' Astronomy: (Astronomicum Caesareum)". Osiris. 1: 356–389. doi:10.1086/368431. ISSN 0369-7827.

- Kremer, Richard L (2011). "Experimenting with Paper Instruments in Fifteenth-and Sixteenth-Century Astronomy: Computing Syzygies with Isotemporal Lines and Salt Dishes". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 42 (2): 223–258. doi:10.1177/002182861104200207.

- Kunitzsch, Paul (2016). "Peter Apian and 'AZOPHI': Arabic Constellations in Renaissance Astronomy". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 18 (2): 117–124. doi:10.1177/002182868701800204.

- Carole Stott, Celestial Charts, Antique Maps of the Heavens, 1995, Studio Editions, London, England P38-39

- Barker, Peter (2008). "Stoic alternatives to Aristotelian cosmology : Pena, Rothmann and Brahe, Summary". Revue d'histoire des sciences (in French). Tome 61 (2): 265–286. doi:10.3917/rhs.612.0265. ISSN 0151-4105.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (1995). "Peter Apian as an astronomical instrument maker". Astronomische Gesellschaft Abstract Series. 11: 107. Bibcode:1995AGAb...11..107W.

- North, J. D. (1966). "Werner, Apian, Blagrave and the Meteoroscope". The British Journal for the History of Science. 3 (1): 57–65. doi:10.1017/s0007087400000194. ISSN 1474-001X.

- Ralf Kern. Wissenschaftliche Instrumente in ihrer Zeit. Volume 1: Vom Astrolab zum mathematischen Besteck. Cologne, 2010. p. 332.

- van Ostroy, Fernand Gratien (1902). Bibliographie de l'oeuvre de Pierre Apian (in French). P. Jacquin.

Further reading

- Kish, George (1970). "Apian, Peter". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 1. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 178–179. ISBN 0-684-10114-9.

- Röttel, K. (Ed.): Peter Apian: Astronomie, Kosmographie und Mathematik am Beginn der Neuzeit, Polygon-Verlag 1995; ISBN 3-928671-12-X. In German.

- Christian Kahl (2005). "Apian, Peter (ursprünglich Bienewitz oder Bennewitz)". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). 24. Nordhausen: Bautz. cols. 107–114. ISBN 3-88309-247-9.

- Peter and Philipp Apian, in German.

- Ralf Kern. Wissenschaftliche Instrumente in ihrer Zeit. Volume 1: Vom Astrolab zum mathematischen Besteck. Cologne, 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Petrus Apianus. |

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Petrus Apianus", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Petrus Apianus.

- Astronomicum Caesareum at the library of the ETH Zurich.

- Astronomicum Caesareum at Rare Book Room.

- Astronomicum Caesareum, Ingolstadt 1540 da www.atlascoelestis.com

- Electronic facsimile-editions of the rare book collection at the Vienna Institute of Astronomy

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High resolution images of works by and/or portraits of Petrus Apianus in .jpg and .tiff format.

- Horoscopion Apiani Generale…, Ingolstadt 1533 da www.atlascoelestis.com

- Cosmographiae Introductio, 1537 from the Collections at the Library of Congress

- Cosmographia, 1544 (1st edition was 1524)

_by_Petrus_Apianus.jpg)