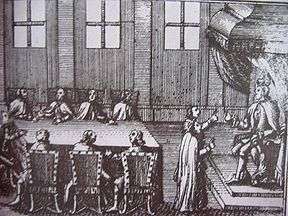

Permanent Council

The Permanent Council (Polish: Rada Nieustająca) was the highest administrative authority in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth between 1775 and 1789 and the first modern executive government in Europe. As is still typically the case in contemporary parliamentary politics, the members of the Council were selected from the parliament or Sejm of the Commonwealth. Even though it exerted some constructive influence in Polish politics and government, because of its unpopularity during the Partitions period, in some Polish texts it was dubbed as Zdrada Nieustająca - Permanent Betrayal.

History

The establishment of an institution of permanent council, an early form of executive government in the late years of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, was originally recommended by the political reformer Stanisław Konarski.[1] It was intermittently under consideration, as permitted by Poland's intrusive neighbors, during the period of government reforms, beginning with the Convocation Sejm of 1764.[1] The Permanent Council was actually created in 1775 by the Partition Sejm, when Empress Catherine the Great of Russia and her ambassador to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Otto Magnus von Stackelberg, became convinced that it was a way of securing the Empire's influence over the internal politics of Poland (control over the Sejm and the King).[1] The Council had remained in continuous operation and was therefore largely immune from szlachta's liberum veto obstructionism, which could be pursued only during the sessions of the Sejm.[1] The Council was also much less prone than the Sejm to other distractions from minor gentry. Empress Catherine and Ambassador Stackelberg believed that the Council would be dominated by anti-royal magnates and that it would put an end to the King's push toward reforms.

The Council was composed of King Stanisław August Poniatowski (who acted as a modern prime minister and had two votes instead of one), 18 members from the Senate and 18 members from the Sejm's lower chamber.[1] The Council, in addition to its administrative duties, would present to the King three candidates for each nomination to the Senate and other main offices.[1] The meetings were supervised by Marshal Roman Ignacy Potocki.

In reality all the Council's members were nominated in accordance with the wishes of Ambassador Stackelberg, who acted as a representative of the Empress, protectress of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth since 1768. Soon after its creation, the Council became an instrument of Russian surveillance over Poland.

The council was divided onto 5 separate ministries called Departments:

- Foreign interests

- Military

- Police ("Good Order")

- Treasury

- Justice[1]

Among the prerogatives of the Council was heading the state administration, preparation of projects of laws and Sejm acts, which were to be later accepted by the parliament, control over law enforcement and interpretation of the law.[1] Although heavily criticized, most notably by the Familia and the so-called Patriotic Party, the Council managed to give rise to a period of economic prosperity in Poland. Its functioning strengthened (despite the intentions of some of its creators) the power of the monarch and reduced the power of the already existing and highly influential magnate-ministers, who were placed under the Council's supervision.[1] The Permanent Council was eliminated in 1789 by the Four-Year Sejm and briefly reinstated in 1793 by the Sejm of Grodno. However, this time it was directly headed by the Russian ambassador. Majority of the Council's members were then bribed by the Russian embassy in Warsaw.

Notable members

- King Stanisław August Poniatowski

- Marshal Roman Ignacy Potocki

- Stanisław Małachowski

- Tomasz Adam Ostrowski

- Ludwik Szymon Gutakowski

- Stanisław Poniatowski (kings' relative)

- Józef Ankwicz

- Michał Jerzy Poniatowski (primate of Poland)

See also

- Ambassadors and envoys from Russia to Poland (1763–1794)

- Lords of the Articles

References

- Józef Andrzej Gierowski – Historia Polski 1764-1864 (History of Poland 1764-1864), Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe (Polish Scientific Publishers PWN), Warszawa 1986, ISBN 83-01-03732-6, p. 60-74