Peralta (Mesoamerican site)

Peralta is a prehispanic mesoamerican archaeological site located in Abasolo Municipality, Guanajuato, just outside the village of San Jose de Peralta in the Mexican state of Guanajuato. The site is reached via Fed 90 from Irapuato. Approximately 15.5 km south of the intersection with Fed 45, take the Irapuato-Huanimaro route southeast (left). Follow the route for about 12.5 km, then turnoff southwest (right) to San Jose de Peralta. Cross the bridge and turn right, and then follow the road out of the village northwest about 1 km. The site is on the left.

| Chichimec-Toltec Culture – Archaeological Site | ||

Peralta Aerial View, site photograph edited | ||

| Name: | Peralta Archaeological Site | |

| Type | Mesoamerican archaeology | |

| Location | San José Peralta, Abasolo, Guanajuato | |

| Region | Mesoamerica | |

| Coordinates | 20°28′17″N 101°24′59″W | |

| Culture | Chichimec – Toltec | |

| Language | ||

| Chronology | 100 to 900 CE | |

| Period | Mesoamerican Postclassical | |

| Apogee | 300 – 650 CE | |

| INAH Web Page | Non existent | |

The center originally occupied about 130 hectares[1] of land and was home to many structures, of which 22 pyramids have been identified,[1] including a multitude of terraced agricultural fields that supported the population. The region was initially settled around 100 AD, with the center reaching its apex between 300 and 650 AD prior to the population's reversion to nomadism.

The site is part of what is known as the “Bajio[2] Tradition” region.

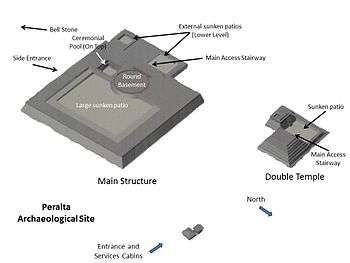

The site developed between 300 and 700 CE, at the time that Teotihuacan was declining and Tula was rising. According to archeologists the city declined and collapsed due to the overexploitation of the surrounding deciduous rainforest and it was abandoned around 900 CE. The site occupies 150 hectares divided into a center with five surrounding settlements. The most important structure is double temple structure, with a “Patio Hundido” (Sunken Patio). Another important building is the Main Structure, called by some La Mesita (The Small Table) or Recinto de los Gobernantes (Governors’ Precinct). It has a large plaza which is considered to have been the main square for the city. Among the walls and other structures a semicircle dedicated to the Danza de Voladores has been discovered.[3]

Peralta and the Bajio Tradition are part of a regional culture, its architecture and ceramic works are different from other mesoamerican societies.[4]

Its large constructions place Peralta among the largest Tradition sites and contain one of the largest ceremonial centers in the region.[4]

Very little is known about these societies inhabiting the Bajio Region, they are thought to have been members of hunter-gatherer, fishing Chichimec groups, it is now known that places such as Peralta were trading confluence routes between central Mexico with northern and western Mesoamerica.[4]

The Peralta inhabitants are believed to have formed autonomous agricultural societies that formed social and religious networks, probably linked by family ties and regional governments. These societies traded foodstuff items, baskets, ornaments and luxury items such as turquoise jewels, shell collars and obsidian items.[4]

Over 1400 years ago, in addition to Peralta, there were five other known important cities in the region; San Bartolome (Tzchté), San Miguel Viejo, Tepozán, Loza Los Padres and Peñuelas. Circular structures confirm the Tradition constant ancient relations with other civilizations. Circular structures are common across prehispanic Mesoamerica.[4]

Background

In the prehispanic times, the Bajio region saw the most human development due to the fertility of the soil and the presence of surface water for agriculture.[5] The oldest group to inhabit the area are called the Chupícuarios, who dominated the center of the Bajío area and were active in between 800 BCE and 300 CE.[6][7] Their largest city is now the site called Chupícuaro, and their influence was widespread being found in the modern states of Zacatecas, Querétaro, Colima, Nayarit, Hidalgo, State of Mexico, Michoacán and Guerrero. Chupícuaro cities were associated with the Toltec city of Tula and when this city fell, these agricultural cities of Guanajuato also went into decline.[6] This and a prolonged drought cause these cities to be abandoned between the 10th and 11th centuries with only the Guamares left ethnically.[8]

Then Chichimeca and other nomadic groups entered the area. These nomadic indigenous groups are generically referred to as Chichimeca, but in reality they were a variety of ethnicities such as the Guachichiles, Pames and Zacatecos. These groups were warlike, semi nomadic and did not practice significant agriculture, nor did they construct cities.[6] Part of the state was also inhabited by the Otomi but they were mostly displaced or dominated by the Purépecha in the southwest and the Chichimeca in other parts.[8] By the 16th century, most of Mesoamerica was dominated by either the Aztec Empire or Purépecha Empire, but Guanajuato was under the control of neither. It was on the northern border of the Purépecha Empire with southern Guanajuato showing significant cultural influence in the southern valleys, and Aztecs had ventured into the area looking for minerals. However, most of the state was dominated by various Chichimeca tribes as part of what the Spanish would call the “Gran Chichimeca.” These Chichimeca were mostly nomadic with some scattered agricultural communities, mostly in the north.[7]

Bajio tradition

Not too long ago, the Bajio Region and a good part of the Mexican central plateau were considered of little archaeological interest. Little was known of native regional societies, beyond the historical data describing an almost uninhabited area two centuries before the conquest.[9]

Data from historical documents indicated that the prehispanic Bajio inhabitants were only Chichimeca, nomadic groups with appropriation economies and belligerents. By 1972, Beatriz Braniff began to explain the Bajio cultures and proposed the contours of a "marginal" region of Mesoamerica, located on the edges of the high cultured regions The apparent influence of large Mesoamerican cities, mainly Teotihuacan in regional development, also departed from the academic debate the possibility of identifying and explaining the specific role played by local societies in the Mesoamerican development.[9]

During the last ten years, archaeological studies have had a major boost in Guanajuato, and several myths of the Bajio past became truth, have provided better founded explanations based on the prehispanic life in this geographic area.[9]

Three aspects seem fundamental: a) the Bajio as an important part of the Mesoamerican universe was a trade communication region and a link between three the cultural areas proposed by Paul Kirchhoff (1967): Central, North and West Mexico; b) theories based on influences determination from major population centers, has now been replaced by understanding the interactions and bi-directional relationships, where the implications of local societies such as Peralta have barely been addressed but no doubt will continue to investigate; c) during the mesoamerican classical period, between 300 and 700 CE, the Bajio developed a notable agricultural population, with a social and political organization structure, in addition to its deep regional cultural roots, that has been identified as the Bajio tradition.[9]

Chichimeca

Chichimeca was the name that the Nahua peoples of Mexico generically applied to a wide range of semi-nomadic peoples who inhabited the north of modern-day Mexico and southwestern United States, and carried the same sense as the European term "barbarian". The name was adopted with a pejorative tone by the Spaniards when referring especially to the semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer peoples of northern Mexico. In modern times only one ethnic group is customarily referred to as Chichimecs, namely the Chichimeca Jonaz, although lately this usage is being changed for simply "Jonáz" or their own name for themselves "Úza".

The Chichimeca peoples were in fact many different groups with varying ethnic and linguistic affiliations. As the Spaniards worked towards consolidating the rule of New Spain over the Mexican indigenous peoples during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the "Chichimecan tribes" maintained a resistance. A number of ethnic groups of the region allied against the Spanish, and the following military colonization of northern Mexico has become known as the "Chichimeca Wars".

Many of the peoples called Chichimeca are virtually unknown today; few descriptions mention them and they seem to have been absorbed into mestizo culture or into other indigenous ethnic groups. For example, virtually nothing is known about the peoples referred to as Guachichiles, Caxcanes, Zacatecos, Tecuexes, or Guamares. Others like the Opata or "Eudeve" are well described but extinct as a people.

Other "Chichimec" peoples maintain a separate identity into the present day, for example the Otomies, Chichimeca Jonaz, Coras, Huicholes, Pames, Yaquis, Mayos, O'odham and the Tepehuánes.

The first description of a modern objective ethnography of the peoples inhabiting La Gran Chichimeca was done by Norwegian naturalist and explorer Carl Sofus Lumholtz in 1890 when he traveled on muleback through northwestern Mexico, meeting the indigenous peoples on friendly terms. With his descriptions of the rich and different cultures of the various "uncivilized" tribes, the picture of the uniform Chichimec barbarians was changed, although in Mexican Spanish the word "Chichimeca" remains connected to an image of "savagery".

The historian Paul Kirchhoff, in his work "The Hunting-Gathering People of North Mexico," described the Chichimecas as sharing a hunter-gatherer culture, based on the gathering of mesquite, agave, and tunas (the fruit of the nopal). While others also lived off of acorns, roots and seeds. In some areas, the Chichimecas cultivated maize and calabash. From the mesquite, the Chichimecas made white bread and wine. Many Chichimec tribes utilized the juice of the agave as a substitute for water when it was in short supply.

The site

Although the site was known for many years by local residents that farmed in and around the structures, it has only been explored three times; the first time was in 1978 by archaeology students; in 1981 explored by salvage archaeologists and the third time in 2002, when several structures were identified.[4]

The archaeological site is dominated by two stepped pyramidal structures with a common, fully enclosed plaza, along with an immense raised platform and additional enclosed plazas. Notably, finds of turquoise, copper bells, seashells, and jadeite in the nearby site of Plazuelas indicate an extensive trade network spanning from Guatemala to the Caribbean to New Mexico. The inhabitants have been identified as part of a unique culture labeled El Bajío. The specific ethnicity of the inhabitants is still under investigation.

The area discovered is only a small percentage of the entire city, which probably extended to Mount Peralta, several kilometers due west and all around the archaeological site.[4]

Natural disaster

The population living in that time, apparently belonged to the Nahuatl and Otomi culture but, as noted, it is not known, because there are no records confirming the culture, hence it can only be assumed from similarities with other archaeological areas.[1]

From available vestiges, it is believed that a natural disaster occurred in 900 CE, diminishing the population, forcing survivors to abandon the city.[1]

Structures

Many structures have been identified, including a ballgame court, but are yet to be explored and uncovered.[4]

Within the site, as many as 22 structure remains have been identified, as well as large farming terraces, thus it is believed that about over 15 thousand inhabitants lived there.[1]

The monumental Peralta architecture is an indication of the highly specialized architects and crafts of its times, it is indeed an impressive architectural expression of the Bajio Tradition. As opposed to the typical mesoamerican open patios or squares, Peralta is distinguished by sunken patios surrounded by rooms and bordered by one or more temples, aligned with equinoxes. Another Peralta characteristic is the presence of circular structures, typically used for ceremonial rituals, probably dedicated to wind, rain and fertility deities. It is believed that Peralta had socio-cultural relations with other regions, such as Guachimontones (Teuchitlán, Jalisco) and Chalchihuites, Zacatecas.[4]

Main structure

The site main structure is unique in Mesoamerica; it is considered the first constructive stage, combining a large rectangular stepped structure with “sunken patios” (pool) and round structures built on top. The structure basement is stepped to adjust to the irregular terrains it was built on.[4]

It is a stepped rectangular structure oriented east-west with external side walls built at an approximate 45 deg., angle, built from stone and earth, stucco and finishings of clay mixed with vegetal fibers. The structure perimeter is stepped and measures some 147 (east-west) by 137 (north-south) meters (482 by 450 ft.).[4]

A top the structure are three different levels, the lower level is composed by a huge sunken plaza, the middle level probably was an area dedicated for spectators or ceremonies participants, on the western side of the top level are a deep “Ceremonial pool” with access ramps and steps to lower levels and remains of a circular basement, measuring some 42 meters in diameter (138 ft.).[4]

It is believed that on the eastern side of the top level rooms were built, probably for governors and high priests. Several human burials with offerings were found in several places of the structure, their origins are unknown. The offerings found are indicative of trade and relations with faraway regions; a turquoise collar is an indication of possible trade with New Mexico and Arizona; shell beads from Pacific Ocean coastal regions; other offerings included two well preserved wooden pieces, pigments, various ceramic vessels, and articles carved from obsidian and flint stone.[4]

The main access stairway to the main structure is located on the western side of the structure, facing a platform and two “sunken patios”. The structure has a secondary entrance, on the southern side.[4]

Sunken patios

On ground level, on the western side of the Main Structure is a large platform containing two large “sunken patios”, probably used for preliminary ceremonial activities.[4]

Sunken Patio 1, is west of the Main Structure and centered with its access stairway, it is larger than and not as deep as the other sunken patio.[4]

Sunken Patio 2 is located south of the other patio.[4]

Double temple

The double temple represents another unique mesoamerican structure, comprising two structures and a plaza, on a single platform.[4]

It is believed the temples followed the typical staged construction practiced throughout Mesoamerica, where every few years a new structure was added over previous ones, by new governors or for new reasons.[4]

These layers or additions to the structures used obsidian stones, turquoise, tepetate and a clay and fiber admixture for construction.[1]

It is believed that on top of the structures existed other constructions for the religious or political purposes of its constructors.[1]

In front of both temples is a sunken plaza, with an intricate series of access stairways, from the outside into the plaza and from the plaza to the structures. The plaza is equipped with a drainage system to prevent flooding.[4]

Stone bell

Peralta was deemed by the villagers of San José to be enchanted by the spirits of its original inhabitants. At the southern-most extent of the archaeological site lies a mineral-rich boulder previously used as a bell by the local elders to call spiritual gatherings at the site.

The stone that rings with a characteristic sound, when struck with another stone (the smaller round stone in the picture). It is a large basalt stone, part of a large stone group, it overhangs on the side of a hill, and it is already fractured, in at least three places.[4]

References

- González, Esaú (March 18, 2007). "Peralta, un poblado que quiere resurgir" [Peralta, a town that wants to return]. Correo Guanajuato (in Spanish). Guanajuato. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved Sep 2010. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - The Bajio (lowlands) is a region of Central Mexico that includes the plains south of the Sierra de Guanajuato, in the state of Guanajuato, as well as parts of the states of Querétaro (the Valley of Querétaro) and Michoacán (particularly the surroundings of Zamora).

- Quintanar Hinajosa, pp. 23–24

- Clément, Marianne C. (January 27, 2011). "Peralta Site Visit notes and photographs". Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Enrique Nalda (1993). "La arqueología de Guanajuato Trabajos recientes" [The archeology of Guanajuato Recent work]. Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). Mexico: Copyright Editorial Raíces S.A. de C.V. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- Jimenez Gonzalez, p. 30

- Beatriz Braniff C. (1993). "Guanajuato en la historia" [Guanajuato in history]. Arqueologia Mexicana (in Spanish). Mexico: Editorial Raíces S.A. de C.V. Archived from the original on November 27, 2010. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- "Nomenclatura" [Nomenclature]. Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México Estado de Guanajuato (in Spanish). Mexico: Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. 2005. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- Cárdenas García, Efraín. "Peralta, Guanajuato" (in Spanish). Colegio de Michoacán - Arquoemex. Archived from the original on 2010-10-26. Retrieved Sep 2010. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)

Bibliography

- Moreno, G., et al., Zonas Archaeológicas en Guanajuato, 2006, Instituto Estatal de la Cultura, Guanajuato, Mexico

- Andrews, J. Richard (2003). Introduction to Classical Nahuatl (Revised ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Gradie, Charlotte M. (1994). "Discovering the Chichimeca". Americas. The Americas, Vol. 51, No. 1. 51 (1): 67–88. doi:10.2307/1008356. JSTOR 1008356.

- Karttunen, Frances (1983). An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Lockhart, James (2001). Nahuatl as Written. Stanford University Press.

- Lumholtz, Carl (1987) [1900]. Unknown Mexico, Explorations in the Sierra Madre and Other Regions, 1890-1898. 2 vols (reprint ed.). New York: Dover Publications. * Powell, Philip Wayne (1969). Soldiers, Indians, & Silver: The Northward Advance of New Spain, 1550-1600. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Secretariá de Turismo del Estado de Zacatecas (2005). "Zonas Arqueológicas" (in Spanish).

- Smith, Michael E. (1984). "The Aztlan Migrations of Nahuatl Chronicles: Myth or History?" (PDF online facsimile). Ethnohistory. Columbus, OH: American Society for Ethnohistory. 31 (3): 153–186. doi:10.2307/482619. ISSN 0014-1801. JSTOR 482619. OCLC 145142543.

External links

- Top 10 Richest People in the World 2000 to 2019 (First Peralta settlers), aftab nama, 2019

- Oficial Abasolo Web Site

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guanajuato. |

- (in Spanish, English, and French) Guanajuato: Governmental portal

- Official financial website