Pequaming, Michigan

Pequaming is an unincorporated community in L'Anse Township of Baraga County in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is located on a narrow point of land that juts into Keweenaw Bay. Although still partially inhabited, Pequaming is one of the largest ghost towns in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.[1][2][3][4][5]

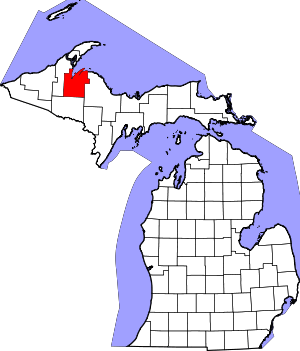

Pequaming, Michigan | |

|---|---|

Pequaming Location within the state of Michigan | |

| Coordinates: 46°51′07″N 88°24′01″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Michigan |

| County | Baraga |

| Township | L'Anse |

| Elevation | 623 ft (190 m) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 49958 |

| Area code(s) | 906 |

| GNIS feature ID | 634613[1] |

History

Originally home to an Ojibwe tribe settlement called Pequaquawaming, which means "the headland", a narrow neck of land almost surrounded by water. The point at Pequaming is in the shape of a bear; the head is called Picnic Point; the tail at the lumberyard, the legs are the two sand beaches, and the back is the shore line. The small Native American village was abandoned by the time American Fur Company trader Peter Crebassa visited in 1836.[2][5]

In 1877, Charles Hebard and Edward Thurber purchased a large tract of land on Keweenaw Point, favored especially for its deep, protected harbor and easy access to timber. The mill began its operations with a capital of $200,000, with stock owned mostly by the Hebard and Thurber families. The mill site was initially leased from David King, Chief of the local Chippewa tribe, and then purchased from his heirs after his death. The company purchased the town site from Mrs. Eliza Bennett in 1877.[3][4][6]

The mill operated under the name of Hebard and Thurber until the partnership was dissolved; Hebard became sole proprietor and renamed his company Charles Hebard and Sons.[3]

At its peak, the company employed a force of two hundred men in the mill working full time, three hundred in the surrounding woods, and nearly a thousand men in all. The company had a stumpage of 100,000 acres (400 km2) of timber lands in Marquette, Baraga, Houghton, and Keweenaw counties. The company owned the buildings and surrounding land, but was known as the "lumberman's utopia" because rent and water were free, and wood could be obtained from the mill for a very small sum per load. The town included the mill, a company store, offices, boarding houses, hotel, livery stable, a bowling alley, bath houses, churches, schools, parks, a band and orchestra, ice rink, and over 100 houses.[3][2][5][6]

The Pequaming mill was the first large-scale lumbering and milling operation in the Lake Superior region, and in the years between 1880 and 1900, the mill cut an average of over 30,000,000 board feet (70,000 m3), 25,000,000 board feet (59,000 m3) in boards and 7,000,000 board feet (20,000 m3) in lath). When officials realized the white pine supply was nearly exhausted, they switched to hemlock and cedar. The pine was made into 1x4 lumber, the cedar into shingles, and hemlock into lath; other products included rail ties and hemlock bark for tanneries. For shipment, the products were loaded into box cars, which were placed onto scows and towed across the bay to Baraga, and then shipped by rail to their destinations. The original sawmill operated until 1887, when it burned in a fire of unknown origins, and was replaced by a larger mill within 60 days.[3][4]

When Charles Hebard died in 1904, his sons Daniel and Charles inherited the company and continued operations. "The Bungalow", which later became Henry Ford's summer home, was constructed in 1913.[3]

In 1922, the Hebards were approached by Ford Motor Company, who wanted to purchase their timber stands only. Mindful of Pequaming's future, the Hebards convinced Ford to purchase the mill and surrounding town as well, and entered into secret negotiations with the hope of completing the sale before operations began. On September 8, 1923, Ford Motor Company purchased the mill and surrounding town for the sum of $2,850,000; the purchase included the double band sawmill, lath and shingle mills, 40,000 acres (160 km2) of timber land, 30,000,000 board feet (70,000 m3) of lumber, 3,000,000 board feet (7,000 m3) of cut logs, the town land and buildings, the railroad, and towing and water equipment.[4][3][6][5]

Renovations on the mill began, and entailed removing the lath and shingle mills, altering the eastern face, dismantling the old burner, and adding a new powerhouse on the west side that housed a 1,000 horsepower (750 kW) triple expansion marine engine from a World War I Liberty boat. After repair and refitting, the sawmill reopened on September 24, with a work force that received $5 per day for an eight-hour shift instead of the previous $3.50 for a longer day.

By the end of February 1925, Ford had connected the Hebard railroad to the Ford railroad in L'Anse, allowing each plant to specialize in one type of wood. Lumber from the Pequaming mill was generally shipped by water to plants in Dearborn, Edgewater, and Chester, mostly in the form of crating lumber. The better grades of lumber were sent by rail to Iron Mountain for use in the auto manufacturing plants. During its peak, the sawmill provided flooring for floorboards, truck boxes, and wood panels for station wagons.

By 1933, car sales has decreased enough, due to the Great Depression, that the demand for lumber was nearly nonexistent. As the mill was idled during that period, Henry Ford created other work for residents by establishing a cooperative farm east of town. As an additional measure, the company store adjusted its food prices and donated clothing and shoes to employees and their families. Ford also used the town as a model for his theories on self-reliance and education; he established a vocational school in his summer home (to be used during the school year), and also opened four one-room elementary and intermediate schools in September 1935. In 1937, the company built a high school, which contained state-of-the-art home economics food and clothing labs and a library, as well as the first fluorescent lights in a Michigan school.[4]

In 1935, the company decided to ship its products by truck, and instituted "just in time" shipping for its logging operations. After the United States entered in World War II, the company's ships were diverted, which resulted in the lumber being trucked to L'Anse and then shipped by rail. However, a shortage of truck tires and increased shipping costs prompted the company to close the mill on October 9, 1942, with the last logs sawed on October 28.

Buildings

Early buildings still in existence today include the water tower, the company store, Henry Ford's summer home and guest house (the "Bungalow"), several houses, and the ruins of the sawmill powerhouse. Today the area boasts many new homes and summer residences.

Buildings of Old Pequaming

- the stamp mill of Hebard and Thurber, began in 1877[3]

- A post office operated in Pequaming from 17 May 1880, until 31 January 1944.[7]

- Two roundhouses existed, one built circa 1940 and the other in 1923[6]

- Pequaming had four elementary schools as of 1940[6] A high school also existed in Pequaming, with a boardinghouse for the students[6]

- There were lumber sheds in Pequaming, built around 1940[6]

Sources

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Pequaming, Michigan

- Monette, Clarence J. (1975). Some Copper Country Names and Places. Lake Linden, Michigan. ISBN 0-942363-04-3.

- Dodge, Roy L. (1990). Michigan Ghost Towns Of The Upper Peninsula. Las Vegas, Nevada: Glendon Publishing. ISBN 0-934884-02-1.

- Classen, Mikel B. "Pequaming: Ghost on the Water". Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Robinson, John (2018). "Historic Michigan: The Part-Ghost Town of Pequaming". 99.1 WFMK.

- Molloy, Lawrence J. (2011). A Guide to Michigan's Historic Keweenaw Copper District: Photographs, Maps and Tours of the Keweenaw - Past and Present. ISBN 978-0-9791772-1-7.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Pequaming Post Office (historical)

Notes and references

- Baragaland Bicentennial 1776-1976. Baraga, Michigan: The Lumberjacks. 1976.

- Cleven, Brian. "Henry Ford's 'Tasty Little Town': Life and Logging in Pequaming" (PDF). Michigan History Magazine (January/February 1999): 19–23. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- L'Anse High School (2005) [1922]. "Outlying Districts: Aura". History of L'Anse township, by the American history class of L'Anse high school. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Library. p. N/A. Retrieved 2008-08-31.

- Holmio, Armas K. E. (2001). (Google Book Search) "Copper Country" Check

|chapterurl=value (help). History of the Finns in Michigan. trans. Ellen M. Ryynanen. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 0-8143-2974-8. Retrieved 2008-08-31.