Penwyllt

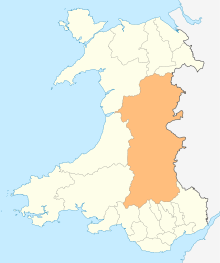

Penwyllt (Welsh: "Wild Headland"[1]) is a hamlet located in the upper Swansea Valley in Powys, Wales.

A former quarrying village, quicklime and silica brick production centre, its fortunes rose and fell as a result of the Industrial Revolution in South Wales. It is now an important caving centre.

Beneath Penwyllt and the surrounding area is the extensive limestone cave system of Ogof Ffynnon Ddu, part of which was the first designated underground national nature reserve in the UK. A corresponding area on the surface is also part of the national nature reserve, on the slopes of Carreg Cadno.

Geography

Penwyllt is a hamlet located in the upper Swansea Valley in Powys, Wales within the Brecon Beacons National Park.

History

Industrialisation

Penwyllt developed primarily as a result of the need for quicklime in the industrial processes in the lower Swansea Valley, taking limestone from the quarries and turning it into quicklime in lime kilns.[2]

Subsequently Penwyllt also supported the Penwyllt Dinas Silica Brick company,[3] which quarried silica sand at Pwll Byfre from which it manufactured refractory bricks, a form of fire brick, at the Penwyllt brick works (closed 1937 or 1939). The bricks were destined for use in industrial furnaces. A narrow-gauge railway, with a rope worked incline ,[4] transported silica sand and stones to the brickworks, which was adjacent to the Neath and Brecon Railway (which on 1 July 1922 became part of the Great Western Railway).[5]

A detailed account of the history of Penwyllt and its industries was provided by Matthews(1991).[6]

Christie 1819-1822

In 1819 Fforest Fawr ("Great Forest of Brecknock") was enclosed or divided up into fields, and large parts of it became the property of John Christie, a Scottish businessman based in London, who had become wealthy through the import of indigo. Christie developed a limestone quarry at Penwyllt, and decided to develop lime kilns there as well. In 1820 he moved to Brecon, and developed the Brecon Forest Tramroad.[7][8]

The tramroad ran from a depot at Sennybridge through Fforest Fawr by way of the limestone quarries at Penwyllt to the Drim Colliery near Onllwyn. A branch served the Gwaun Clawdd Colliery on the northern slopes of Mynydd y Drum and was extended to the Swansea Canal.

Christie was declared bankrupt in 1827 and most of his assets, including the tramroad, eventually passed to his principal creditor, Joseph Claypon, of the banking house of Garfit & Claypon in Boston, Lincolnshire.[9]

Claypon 1827-1850

Claypon took over Christie's assets, and came to the conclusion that shipping lime, coal, iron ore and quicklime south to the larger industrial premises in the southern Swansea Valley was more productive than trying to serve a small rural population of the Usk valley to the north.

They quickly sold or leased the farms and developments north of Fforest Fawr and concentrated on expanding the lime kilns at or around Penwyllt. In total there were fifteen lime kilns at Penwyllt:

- Penwyllt quarry: two lime kilns created in the railway age by "Jeffreys, Powell and Williams", dated 1878[2]

- Pen-y-foel: a bank of four kilns near the Penwyllt Inn erected in around 1863 to 1867 by, it is thought, the Brecon Coal & Lime Co. There is a loading bank for railway wagons in front of the kilns[10]

- Twyn-disgwylfa: Built by Joseph Claypon between 1836 and 1842, the bank of seven kilns has been largely destroyed by quarry tipping. Only one draw arch can now be seen[11]

- Twyn-y-ffald: The 1825 and 1827 kilns built by Joseph Claypon have been largely demolished, although the single draw arch can still be seen[12]

Second half of the 19th century

On 29 July 1862, an Act of Parliament created the Dulais Valley Mineral Railway,[13] to transport goods to the docks at Briton Ferry, Neath built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. The population of Penwyllt grew on this increased transport ability to over 500 citizens by the 1881 Census.

After being authorised to extend the railway to Brecon, it changed its name to the Neath and Brecon Railway. The railway agreed to co-operate with the Swansea Vale Railway to create the Swansea Vale and Neath and Brecon Junction Railway linking the railway fully into Neath, as well as the South Wales Railway mainline. An early and unsuccessful purchaser of the new Fairlie locomotive, when in 1863 the railway reached Crynant, coal mining quickly expanded.[14] At Crynant several new mines were opened including the Crynant colliery, Brynteg colliery in 1904, Llwynon colliery in 1905, Dillwyn colliery, and Cefn Coed colliery 1930[15]

Craig-y-nos railway station at Craig-y-nos/Penwyllt was in part funded by opera singer Adelina Patti, who lived at and extended Craig-y-Nos Castle. She built a road from the castle to the station and a separate waiting room. The railway supplied her in return with her own railroad car, which she could request to go anywhere within the United Kingdom.

Decline 1870

As the industrialisation declined with reducing economic stocks of coal, iron ore and limestone and the development of new technologies on a larger scale on the coast of South Wales, particularly at Port Talbot and Llanwern, Penwyllt declined.

By 1870 the seven blast furnace ironworks of Ynyscedwyn had only one working furnace.

20th century

World War II created the final closure, as the need to scale production upwards for the larger coastal meant the heavily manual process of Penwyllt quarry was uneconomic compared to other British and foreign facilities which could bulk ship by sea. The Penwyllt Inn,[16] or 'Stump' as it was often known, closed in 1948, and in October 1962 all passenger services were withdrawn by British Rail from Neath and Brecon Railway line. The line north of Craig-y-nos/Penwyllt station closed to Brecon on closure of Brecon station, and by the end of the 1960s the population had fallen to 20 people. The railway line remained open south to Neath until 1977 to serve the quarry until it ceased major production and effectively closed.[17]

Many of the former industrial buildings, commercial properties and houses of Penwyllt were demolished in the early 1980s, being both beyond economic repair and unneeded.

21st Century

The former pub survives as private accommodation for cavers. The former Craig-y-nos/Penwyllt station survives in good repair as a private holiday cottage. Patti Row, a historic block of back-to-back houses dating from the days of the Brecon Forest Tramroad,[18] survives in a derelict state. The only group of terraced houses still occupied are in Powell Street and form the headquarters of the South Wales Caving Club,[19] and the South & Mid Wales Cave Rescue Team [20] SWCC Cottage[21]

The quarry, though not the railway, re-opened in 2007 to provide limestone for the works associated with a new gas pipeline being laid through South Wales. In 2008 it was again dormant. In 2009 it was operational but at a relatively low level of activity.

References

- Cardiff Naturalists' Society

- Penwyllt - Craig-y-nos kilns

- Images of Wales

- The Colliery Guardian, Vol 85 pp1325-6, 19 June 1903

- Barrie, D.S.M., A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain, Vol. 12 South Wales. David & Charles, 1980. ISBN 0-7153-7970-4

- Matthews, Helen, (1991), "Penwyllt Village, Growth, Development and Decline", Local History Dissertation, University College of Swansea (25MB pdf file)

- P R Reynolds, The Brecon Forest Tramroad (Swansea, 1979)

- Stephen Hughes, The Brecon Forest Tramroads: the archaeology of an early railway system, (Aberystwyth : Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Wales, 1990)

- Victorian Ystradgynlais - The Brecon Forest Tramroad

- Penwyllt, Pen-y-foel kilns

- Penwyllt - Twyn-disgwylfa kilns

- Penwyllt - Twyn-y-ffald kiln

- http://www.swansea.gov.uk/westglamorganarchives/index.cfm?articleid=13523&articleaction=print

- "Neath Port Talbot Museum Service - All For Coal". Archived from the original on 27 April 2007. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- http://www.swansea.gov.uk/westglamorganarchives/index.cfm?articleid=13542&articleaction=print

- Images of Wales

- cyn.JPG :: Craig y Nos/Penwyllt Station looking north on 14 April 2006. The Neath & Brecon line to this point lingered on to serve the adjacent quarry until 1977 (officially closed 1981)

- Hughes, Stephen, The Brecon Forest Tramroads, RCAHM in Wales, 1990, ISBN 1-871184-05-3

- South Wales Caving Club

- South & Mid Wales Cave Rescue Team

- SWCC Cottage