Pedrail wheel

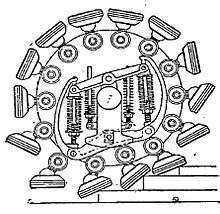

The pedrail wheel is a type of wheel developed in the early 20th century for all-terrain locomotion. They consist of a series of "feet" (pedes in Latin) connected to pivots on a wheel. As the wheel turns, the feet come into contact with the ground, and rotate so they remain flat to the ground as the wheel moves over them. Pedrail wheels may be simple systems with the feet connected to a rigid wheel, but more complex systems including various built-in suspension systems were designed to improve performance on uneven ground. The system was used in agricultural machinery.

Pedrail wheels should not be confused with dreadnaught wheels which have articulated rails attached at the rim for the wheel to roll over (also known as endless railway wheels). Both designs were replaced by continuous track systems.

Definition

According to the 1913 Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary, a pedrail is:

A device intended to replace the wheel of a self-propelled vehicle for use on rough roads and to approximate to the smoothness in running of a wheel on a metal track. The tread consists of a number of rubber shod feet which are connected by ball-and-socket joints to the ends of sliding spokes. Each spoke has attached to it a small roller which in its turn runs under a short pivoted rail controlled by a powerful set of springs. This arrangement permits the feet to accommodate themselves to obstacles even such as steps or stairs.

— Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary, C&G Merriam, 1913.[2]

Invention

The pedrail wheel was invented in 1903 by the Londoner Bramah Joseph Diplock.[3][4] It consists in the adjunction of feet (Latin radical "ped") to the rail of a wheel, in order to improve traction and facilitate movement in uneven or muddy terrain.[1] Sophisticated pedrail wheels were designed, with individual suspension for each foot, which would facilitate the contact with uneven terrain.

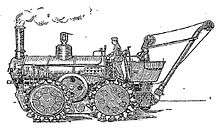

Bramah Joseph Diplock also invented the pedrail locomotive which was featured in the 7 February 1904 New York Times.[1]

Fiction

H. G. Wells, in his short story The Land Ironclads, published in The Strand Magazine in December 1903, described the use of large, armoured cross-country vehicles, armed with automatic rifles and moving on pedrail wheels, to break through a system of fortified trenches, disrupting the defence and clearing the way for an infantry advance:

They were essentially long, narrow and very strong steel frameworks carrying the engines, and borne upon eight pairs of big pedrail wheels, each about ten feet in diameter, each a driving wheel and set upon long axles free to swivel round a common axis. This arrangement gave them the maximum of adaptability to the contours of the ground. They crawled level along the ground with one foot high upon a hillock and another deep in a depression, and they could hold themselves erect and steady sideways upon even a steep hillside.

— [5]

In War and the Future, Wells acknowledged Diplock's pedrail as the origin for his idea of an all-terrain armoured vehicle:[6]

The idea was suggested to me by the contrivances of a certain Mr. Diplock, whose "ped-rail" notion, the notion of a wheel that was something more than a wheel, a wheel that would take locomotives up hill-sides and across ploughed fields, was public property nearly twenty years ago

— [7]

Although Wells describes the pedrail wheels in detail, a number of authors have mistakenly taken his description to be of some form of caterpillar track. Diplock's version of an endless track was not designed until some ten years after the publication of Wells' story. The pedrail wheel played no part in the design of the first British tanks.

Chaintrack

In 1910 Diplock abandoned the Pedrail Wheel and began developing what he called the Chaintrack, in which fixed wheels ran on a moving belt, very like the caterpillar track as it is now understood.[8] It was a complicated and high-maintenance system, and in 1914 Diplock eventually produced a version on a simpler, single wide track.[9] With a body fitted, the machine could carry a ton of cargo and be pulled with minimal effort by a horse. It demonstrated the attributes of the caterpillar track: low friction and low ground pressure.

Notes

- "The Perambulating Pedrail", The New York Times, 7 February 1904.

- "Pedrail", The Free dictionary.

- Wallistayler, AJ, Motor Vehicles for Business Purposes, p. 271.

- Popular Science, September 1933, p. 96.

- Wells, HG (December 1903), The Land Ironclads, Zeitcom, §4, archived from the original on 5 March 2009

- Wells, p. 93.

- Wells, HG, War and the Future, p. 71-93

- Diplock's 1910 patent

- Diplock's 1914 patent.

Bibliography

- Harris, JP (1995), Men, ideas, and tanks: British Military Thought and Armoured Forces, 1903–1939 (hardback), War, Armed Forces and Society, 1, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-3762-X.

- Wells, Herbert George (30 June 2008) [1917], War and the Future, Kessinger, ISBN 0-497-97078-3.

- White, BT (1963), British Tanks 1915–1945, Shepperton: Ian Allan.

References

- Glanfield, John (2006), The Devil's Chariots: The Birth and Secret Battles of the First Tanks, Sutton Pub, ISBN 0-7509-4152-9.