Pearl Witherington

Cecile Pearl Witherington Cornioley CBE (24 June 1914 – 24 February 2008), code names Marie and Pauline, was an agent for the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) during World War II. The purpose of SOE was to conduct espionage, sabotage, and reconnaissance in occupied Europe against the Axis powers. SOE agents allied themselves with French Resistance groups and supplied them with weapons and equipment parachuted in from England.

Pearl Witherington | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Marie, Pauline[1] |

| Born | 24 June 1914 France |

| Died | 24 February 2008 (aged 93) France |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom/France |

| Service/ | Special Operations Executive, First Aid Nursing Yeomanry |

| Years of service | 1940–1944 / 1943–1944 (SOE) |

| Unit | Stationer, Wrestler |

| Awards | MBE, CBE, Legion d'honneur |

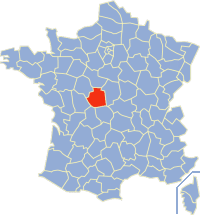

Witherington was born in Paris to British parents. She parachuted into France in September 1943 as a courier for the SOE Stationer Network and in May 1944 became head of the SOE Wrestler Network in the Indre region in central France. She was the only woman to lead an SOE network and associated resistance groups, called maquis, in France.[2][3]

Witherington's network, comprising about 2,000 maquisard fighters after the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944, was especially efficient in sabotaging railroads and telephone lines. The official historian of the SOE, M.R.D. Foot, characterized the Wrestler network as "highly successful."[4] She was a recipient of the Order of the British Empire from the United Kingdom and the Legion of Honor and Croix de Guerre from France.

World War II

Courier for the SOE

Cecile Pearl Witherington was born and raised in France by British expatriate parents, and was a British subject. Her father had been born into money but drank most of it away, and Pearl often had to negotiate with his creditors to save them from destitution. She was employed at the British embassy in Paris and engaged to Henri Cornioley (1910–1999) when the Germans invaded France in May 1940.[5] Her fiancee had joined the British army in February 1940 and she did not see him again for three and one-half years.[6]

She escaped from occupied France with her mother and three sisters in December 1940. The family arrived in London in July 1941 where she found work with the Air Ministry, specifically the Women's Auxiliary Air Force.[7] Determined to fight back against the German occupation of France, and wanting a more active role in the fight, she joined Britain's Special Operations Executive (SOE) on 8 June 1943. In training she emerged as the "best shot" the service had ever seen.[8][7] Despite her prowess with firearms, she never carried a gun during her mission in France.[9]

Given the code name "Marie", Witherington was dropped by parachute into occupied France on 22 September 1943, landing near Tendu in Indre Department.There she joined Maurice Southgate, leader of the SOE Stationer Network and Jacqueline Nearne, Southgate's courier, and reunited with her fiancee. Over the next eight months, posing as a cosmetics saleswoman, Witherington also worked as a courier.[11] The Stationer network covered a large area in central France and Witherington was effectively homeless, spending nights sleeping on trains as she traveled from one place to another delivering messages and undergoing frequent checks of her (false) identity cards by the Gestapo and French police. Rheumatism put her out of action for a few weeks.[12]

An exhausted Jacqueline Nearne returned to Great Britain in April 1944 and the Gestapo arrested Southgate on May 1, 1944 and deported him to Buchenwald concentration camp. Witherington was fortunate not to be arrested with him. Witherington and Southgate's wireless operator, Amédée Maingard were with Southworth the day he was arrested, but Witherington said that Maingard was worn out and that he needed to take the afternoon off. While the two of them were picnicking, Southworth was arrested. Survival as an SOE agent was often luck.[13] [14]

With Southworth a prisoner of the Germans, Witherington formed and became leader of a new SOE network, Wrestler, under the new code-name "Pauline", in the Valencay–Issoudun–Châteauroux triangle. She organised the network with the help of her fiancee, Henri Cornioley. Witherington did not attempt to issue orders to the maquis groups directly, but found a willing French colonel to do so. Witherington worked closely with the adjoining SOE Shipwright network, headed by her former colleague Amédée Maingard. Together, their networks caused more than 800 interruptions of railway lines in June 1944 focused on cutting the main railroad line between Paris and Bordeaux. Putting those lines out of operation hindered the German effort to transport men and material to the battle front in Normandy.[15]

Attacked and attacking

On the morning of June 11, 1944, German soldiers attacked Witherington at the Les Souches chateau, her headquarters near the village of Dun-le-Poëlier. Only a few maquis and non-combatants were present when the Germans arrived. Under fire, Witherington hid the tin where she kept a large amount of money and fled to a wheat field where she hid until nightfall. Her fiancee, Henri Cornioley, also hiding in a wheat field, counted 56 truckloads of Germans participating in the operation. According to Witherington, the Germans didn't try to find the hidden maquis and the SOE agents, confining themselves to destroying the weapons they found in the chateau. The attack on Witherington's headquarters was part of a larger operation in which 32 maquis were killed.[16]

The attack left Witherington in "a hopeless state--we had nothing left, no weapons and no radio." She bicycled to Saint-Viâtre to meet an SOE operative, Philippe de Vomécourt, nom de guerre "Saint Paul," and radioed London requesting resupply. On June 24, three planes air-dropped supplies and Witherington was back in operation. The number of maquis in her region quickly ballooned to as many as 3,500 as the Normandy invasion emboldened young men to join the resistance. She and Cornioley divided the maquis into four subsections, each with its leader. SOE in Great Britain supported the maquis groups by parachuting 60 planeloads of arms and material to them. Witherington had long requested a military commander to help her and on July 25 Captain Francis Perdiset arrived to assist in the military operations of the maquis in Witherington's sector. She objected to characterizations of her work as "bang-bang-bang, she blew up trains." She said, "It's just not true. All I did was to visit and arm the resisters."[17]

German surrender

In late August 1944, the four groups of maquis in Witherington's Wrestler network were ordered by French authorities, now asserting their control of the maquis as the Germans were being pushed out of France, to move to the Forest of Gatines near the town of Valencay. The objective was to stop the German army in southern France from linking up with German forces in northern France. Witherington opposed the movement, but nevertheless accompanied the Wrestler maquis. On September 9-10, in a battle more than 19,000 German soldiers under the command of General Botho Elster were threatened by French maquis. Fearing retribution, Elster didn't want to surrender to the maquis, but instead to a "regular army" and negotiated a surrender with American General Robert C. Macon. The French maquis who had harassed the Germans were not invited to attend or participate in the surrender on September 11 at Issoudun or the formal surrender on September 16 at Beaugency bridge. "Thus," said historian Robert Gildea, "the most tangible contribution of the FFI [ French Forces of the Interior ] was not even registered."[18] Witherington was furious. She said that after the surrender ceremony the Americans showered the German soldiers with "oranges, chocolate, the whole works. But that's an old story, you know, soldiers were welcoming other soldiers. We weren't soldiers."[19]

Witherington was not alone in her fury. French men and women "who had next to nothing" looked on as the Americans distributed rations and luxuries to the Germans. American flags were torn down and outraged letters were published in local and national newspapers.[20]

On September 21, 1944, Witherington and the British personnel under her command were ordered to return to the United Kingdom, their mission completed. She returned with an "extraordinary--and probably unique--breakdown of her expenditure in the field: amounting to several million francs, it listed in meticulous detail every purchase she had made, even including entries for cigarettes and razor blades."[21]

Honours

A colleague, Michel Mockers

After the war, Witherington was recommended for the Military Cross, but as a woman, she was ineligible[23] and instead was offered an MBE (Civil Division). Witherington rejected the medal with an icy note pointing out that "there was nothing remotely 'civil' about what I did. I didn't sit behind a desk all day". She accepted a military MBE and many years later was awarded the CBE aka Commander of the Order of the British Empire. She was also a recipient of the Légion d'honneur.[24]

In April 2006, age 92, after a six-decade wait, Witherington was awarded her parachute wings, which she considered a greater honour than either the MBE or the CBE. She had completed three training parachute jumps, with the fourth operational. "But the chaps did four training jumps, and the fifth was operational - and you only got your wings after a total of five jumps", Witherington said. "So I was not entitled - and for 63 years I have been moaning to anybody who would listen because I thought it was an injustice."[25]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

| Commander of the Order of the British Empire | Member of the Order of the British Empire | 1939–1945 Star | France and Germany Star |

| Defence Medal | War Medal | Légion d'honneur (Chevalier) | |

Private life

Witherington married Henri Cornioley in Kensington Register Office on 26 October 1944; they had a daughter, Claire. With the help of journalist Hervé Larroque, Witherington's autobiography, Pauline, was published in 1997 (ISBN 978-2-9513746-0-7). The interviews of Pauline were edited by Kathryn J. Atwood into a straight narrative in 2013 and published as Codename Pauline: Memoirs of a World War II Special Agent. Much of her wartime service is also included in the book Behind Enemy Lines with the SAS.[8]

After the war, Witherington worked for the World Bank. In 1991, she and her husband helped to establish the Valencay SOE Memorial commemorating 104 SOE agents who died in the line of duty. The couple retired near Valencay, one of the places she frequented during World War II.[26]

Her story has been cited as the inspiration for the Sebastian Faulks novel Charlotte Gray,[8] which was made into a film of the same name starring Cate Blanchett in 2001, although Faulks denied this in an interview with The Guardian.[27] However, in parallel with the story in Charlotte Gray, Witherington went to France partially to look for her fiancee, Henri Cornioley, also with the SOE in France.[8] Author Ken Follett includes a quote about Witherington's accomplishments at the end of his novel, Jackdaws.[28]

Death

Pearl Witherington Cornioley died, aged 93, in a retirement home in the Loire Valley of France.[8]

See also

- Binney, Marcus. The Women Who Lived For Danger: The Women Agents of SOE in the Second World War, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 2002 (Chap. 7)

- Witherington, Pearl, with Hervé Larroque, ed. Atwood, Kathryn J., Codename Pauline: Memoirs of a World War II Special Agent, Chicago Review Press, 2015

References

- Pearl Cornioley, obituary, The Daily Telegraph, 26 February 2008

- Olson, Lynne (2017), Last Hope Island, New York: Random House, p. 272, 344

- Rossiter, Margaret L. 1986), Women in the Resistance, New York: Praeger, p. 181

- Foot, M. R. D. (1966), SOE in France, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, pp. 122, 436, 440

- SOE agent profile of Pearl Witherington, nigelperrin.com; accessed 4 September 2017.

- Cornioley, Pearl Witherington and Larroque, Hervé (2013), ed. by Kathryn J. Atwood, Code Name Pauline, Chicago: Chicago Review Press, p. 18

- Atwood, Kathryn J. (2011). Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 186. ISBN 9781556529610. OCLC 988003271.

- Martin, Douglas (11 March 2008). "Pearl Cornioley, Resistance Fighter Who Opposed the Nazis, Is Dead at 93". International New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- Perrin, Nigel, "Pearl Witherington," . accessed 16 Dec 2019

- Foot, M.R.D. (1966), S.O.E in France. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, pp 47-48

- Atwood, Kathryn J. (2011). Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. p. 187. ISBN 9781556529610.

- Perrin, . accessed 16 Dec 2019

- Foot, p. 122

- Perrin, . accessed 16 Dec 2019

- Foot, pp. 122, 381, 389, 398

- Witherington, pp. 74-79

- Witherington, pp. 82-88

- Gildea, Robert (2015), Fighters in the Shadows, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p. 406.

- Witherington, pp 96-101

- Ford, Roger (2004), Steel from the Sky, London: Cassell Military Paperbacks, p. 39

- Perrin,

- Rossiter, p. 181

- "Pearl Cornioley profile". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. 26 February 2008.

- "War heroine 'not classed leader'". BBC News Online. 1 April 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- "BBC NEWS - UK - War heroine honoured 63 years on". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Perrin, , accessed 9 Nov 2019.

- David Pallister (1 April 2008). "Sharpshooter, paratrooper, hero: the woman who set France ablaze". London, UK: The Guardian. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Follett, Ken (9 April 2008). Jackdaws. Pan Books. ISBN 0333783026. OCLC 440897819.

External links

- Obituary: Pearl Witherington Cornioley, timesonline.co.uk

- Biodata, spartacus-educational.com

- Award of Parachute Wings to Pearl Witherington Cornioley, bbc.co.uk

- "The Real 'Charlotte Grays' -- Pearl Witherington, Extraordinary Courage," BBC Channel 4, undated