Pearl Hart

Pearl Hart (born Pearl Taylor; c. 1871 – after 1955) was a Canadian-born outlaw of the American Old West. She committed one of the last recorded stagecoach robberies in the United States, and her crime gained notoriety primarily because of her gender. Many details of Hart's life are uncertain, with available reports being varied and often contradictory.

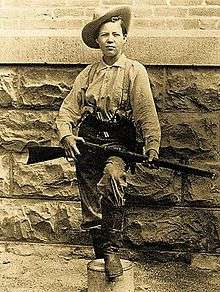

Pearl Hart | |

|---|---|

Hart at the Yuma Territorial Prison | |

| Born | Pearl Taylor November 13, 1876 Lindsay, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | December 28, 1955 (Aged 79)[1] Gila County, Arizona, United States |

| Other names | Talo Halo, Bandit Queen, Lady Bandit, Pearl Taylor Hart, Pearl Bywater |

| Criminal status | Pardoned |

| Spouse(s) | Frank Hart, George Calvin “Cal” Bywater |

| Children | Joe and Emma Hart |

| Motive | Money |

| Conviction(s) | Interference with U.S. mail |

| Criminal charge | Stagecoach robbery Possession of stolen goods |

| Penalty | 5 years (2 served) |

Early life

Hart was born Pearl Taylor in the Canadian village of Lindsay, Ontario. Her parents were both religious and affluent, those provided their daughter with the best available education.[2]:49 At the age of 16, she was enrolled in a boarding school where she became enamored with a young man, named Hart, who has been variously described as a rake, drunkard, and/or gambler.[3] The two of them eloped, but Hart soon discovered that her new husband was abusive and left him to return to her mother.[4]

Hart reconciled with and left her husband several times. During their time together they had two children, a boy and a girl, whom Hart sent to her mother who was then living in Ohio. In 1893, the couple attended the Chicago World's Fair, where he worked for a time as a midway barker. She in turn developed a fascination with the cowboy lifestyle while watching Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show.[3] At the end of the Fair, Hart left her husband again on a train bound for Trinidad, Colorado, possibly in the company of a piano player named Dan Bandman.[2]:50

Hart described this period of her life thus: "I was only twenty-two years old. I was good-looking, desperate, discouraged, and ready for anything that might come. I do not care to dwell on this period of my life. It is sufficient to say that I went from one city to another until some time later I arrived in Phoenix".[4] During this time Hart worked as a cook and singer, possibly supplementing her income as a demimondaine (prostitute).[2]:50 There are also reports she developed a fondness for cigars, liquor, and morphine during this time.[3]

A story of this period claims that while in Phoenix, Hart ran into her husband. He convinced her to come back to him and move to Tucson. Once the money she had saved ran out, he returned to his abusive ways. The story continues by saying that when the Spanish–American War began he volunteered for military service. Hart then shocked observers by declaring that she hoped he would be killed by the Spanish.[4] A variation of this story has Bandman instead of her husband leaving Hart for war.[5]

Life of crime

By early 1898, Hart was in the town of Mammoth, Arizona. Some reports indicate she was working as a cook in a boardinghouse.[2]:50 Others indicate she was operating a tent brothel near the local mine, even employing a second lady for a time.[6] While doing well for a time, her financial outlook took a downturn after the mine closed. About this time Hart attested to receiving a message asking her to return home to her seriously ill mother.[2]:51

Looking to raise money, Hart and an acquaintance known only as "Joe Boot" (likely an alias) worked an old mining claim he owned, but found no gold in the claim.

The pair decided to rob a stagecoach that traveled between Globe and Florence, Arizona.[7] The robbery occurred on May 30, 1899, at a watering point near Cane Springs Canyon, about 30 miles southeast of Globe.[2]:51 Hart had cut her hair short and dressed in men's clothing. Hart was armed with a .38 revolver while Boot had a Colt .45.[3] One of the last stagecoach routes still operating in the territory, the run had not been robbed in several years and thus the coach did not have a shotgun messenger.[2]:51 The pair stopped the coach and Boot held a gun on the robbery victims while Hart took $431.20 (equivalent to $13,252 in 2019) and two firearms from the passengers. After returning $1 to each passenger, she then took the driver's revolver. After the robbers had galloped away on their horses, the driver unhitched one of the horses and headed back to town to alert the sheriff.[2]:52

Accounts of the next few days vary. According to Hart, the pair took a circuitous route designed to lose anyone who followed while they made their future plans.[4] Others claim the pair became lost and wandered in circles.[8]:399 Regardless, a posse led by Sheriff Truman of Pinal County caught up with the pair on June 5, 1899. Finding both of them asleep, Sheriff Truman reported that Boot surrendered quietly while Hart fought to avoid capture.[9]

In and out of Jail

Following their arrest, Boot was held in Florence while Hart was moved to Tucson, the jail lacking any facilities for a woman.[2]:53–54 The novelty of a female stagecoach robber quickly spawned a media frenzy and national reporters soon joined the local press clamoring to interview and photograph Hart.[7] One article in Cosmopolitan said Hart was "just the opposite of what would be expected of a woman stage robber," though, "when angry or determined, hard lines show about her eyes and mouth".[3] Locals also became fascinated with her, one local fan giving her a bobcat cub to keep as a pet.[3]

The room Hart in which was held was not a normal jail cell, but made of lath and plaster.[6] Taking advantage of the relatively weak building material, and possibly with the aid of an assistant, Hart escaped on October 12, 1899, leaving an 18-inch (46 cm) hole in the wall.[10] She was recaptured two weeks later near Deming, New Mexico.[6]

Hart and Boot came to trial for robbing the stagecoach passengers in October 1899. During the trial Hart made an impassioned plea to the jury, claiming she needed the money to be able to go to her ailing mother. Judge Fletcher M. Doan was shocked and angered when the jury found her not guilty and scolded the jurors for failure to perform their duties.[8]:400 Immediately following the acquittal, the pair was rearrested on the charge of tampering with U.S. mail.[11] The pair were convicted during their second trial, with Boot receiving a sentence of thirty years and Hart a sentence of five years.[4]

Both Hart and Boot were sent to Yuma Territorial Prison to serve their sentences. Boot became a prison trusty, driving supply wagons to chain gangs working outside the walls. One day while driving a wagon he escaped and was never seen again.[3] At the time of his escape, Boot had completed less than two years of his sentence.[8]:399

The attention Hart had received in jail continued once she was imprisoned. The warden, who enjoyed the attention she attracted, provided her with an oversized 8 by 10 feet (2.4 by 3.0 m) mountainside cell that included a small yard and allowed her to entertain reporters and other guests as well as pose for photographs.[3][7] Hart, in turn, used her position as the only female at an all-male facility to her advantage, playing admiring guards and prison trusties off of each other in an effort to improve her situation.[8]:400

Hart's release from prison came in the form of a December 1902 pardon from Arizona Territorial Governor Alexander Brodie.[5] The reason for this pardon, given on the condition she leave the territory, is unclear. At the time, Hart claimed she was needed in Kansas City to play the lead in a play, written by her sister, about her life of crime.[12] A later rumor emerged in 1964, following the death of all potentially involved parties, alleging Hart was pardoned because she had become pregnant in a manner which would embarrass the prison.[4] There are accounts that she and the warden were lovers. There is no evidence Hart ever had a third child, so this rumor, if true, may indicate a successful ploy on Hart's part.[3] Upon release from prison, Hart was provided with a train ticket to Kansas City.[8]:400

Later life

After leaving prison, Hart largely disappeared from public view. She had a short-lived show where she re-enacted her crime and then spoke about the horrors of Yuma Territorial Prison.[8]:400–401 Following this she worked, under an alias, as part of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show.[3] In 1904, Hart was running a cigar store in Kansas City when she was arrested for receiving stolen property.[3] She was acquitted of the charge.[6]

Accounts have her returning to Tucson 25 years after her imprisonment to visit the jail cell that once held her.[6] A census taker in 1940 claimed to have discovered Hart living in Arizona under a different name,[3] as she had married again. She lived a private life with her husband of 50 years, George Calvin “Cal” Bywater. She is acknowledged as the only known female stagecoach robber in Arizona's history, earning her the nicknames of “Bandit Queen” or “Lady Bandit”.

In Popular Culture

In addition to being a staple of pulp western fiction, Hart's exploits have been featured in other venues.[7] Her adventures are mentioned in the early 1900s film Yuma City.[12] The play Lady with a Gun and the musical The Legend of Pearl Hart are also based upon Hart's story.[7][13]

The band Volbeat have a song named after Hart on their album Outlaw Gentlemen & Shady Ladies,[14] about the robbery of the Globe to Florence stagecoach, with mention of the $1 returned to each of the passengers.

Pearl Hart was the subject of an episode of Tales of Wells Fargo that aired on May 9, 1960, played by Beverly Garland.[15] She was also the subject of a Death Valley Days episode from March 17, 1964, titled "The Last Stagecoach Robbery", with Anne Francis playing the part of Pearl.[16]

Pearl Hart is the main character for the play Waiting Women by Latina playwright Silvia Gonzalez S., published by Dramatic Publishing 1998. The play follows her story from her vaudeville act, her reasons and dramatization of her stage coach robbery, and her experience in the women's side of the Yuma Territorial Prison with women of color. The entire play is based on actual people of this time period. The play was first produced by Mutt Rep directed by Liz Ortiz-Mackes, with Don Glenn as artistic director. Productions continued across the country with the most recent at Hanford Multicultural Theater Company in March 2019.

John Fluevog designed a pair of high-heeled shoes named after Pearl Hart.[17]

References

- Pearl Hart at Find a Grave

- Brown, Wynne (2003). More Than Petticoats: Remarkable Arizona Women. Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 0762723599. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- Matas, Kimberly (October 31, 2008). "Pearl Hart: Smooth-talking card shark led Pearl's slide to perdition". Arizona Daily Star. (Note: Different sources list Hart's given name as Brett, Frank, or William.)

- Simpson, Claudette (December 18, 1981). "Pearl Hart: Arizona's Woman Bandit". The Courier. p. 3 – via Google News Archive.

- "May 30, 1899: Pearl Hart holds up an Arizona stagecoach". This Day in History. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on May 2, 2009. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- Schwartz, John (November 2, 2000). "Pearl Hart left mark on our outlaw history". The Daily Courier. p. 4A – via Google News Archive.

- Anderson, Parker (July 28, 2002). "How A Woman Robber Became A Famous Outlaw". The Daily Courier. p. 6A – via Google News Archive.

- Wagoner, Jay J (1970). Arizona Territory, 1863-1912: A Political History. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. Retrieved April 13, 2019.

- "Arizona Robbers Caught". New York Times. June 6, 1899. p. 1.

- "Escape of Pearl Hart". Dallas Morning News. October 12, 1899. p. 5.

- "Pearl Hart Acquitted". New York Times. November 17, 1899. p. 9.

- Goodman, Burt (September 4, 1989). "Pearl Hart: Actress was notorious bandit". Mohave Daily Miner. p. 2 – via Google News Archive.

- "'Pearl Hart' Musical Plays Extra Performance, 6/20". BroadwayWorld.com. June 16, 2006.

- "Outlaw Gentlemen & Shady Ladies by Volbeat". Amazon.co.uk. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- IMDb - Tales of Wells Fargo (1957-1962); "Pearl Hart"

- IMDb – Death Valley Days (1952–1970); "The Last Stagecoach Robbery"

- "Bellevues Pearl Hart". Fluevog Shoes. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pearl Hart. |

- "An Arizona Episode". Cosmopolitan. 27 (6): 673–77. October 1899 – via Google Books. Hart's account of events leading to the robbery.