Payload

Payload is the carrying capacity of an aircraft or launch vehicle, usually measured in terms of weight. Depending on the nature of the flight or mission, the payload of a vehicle may include cargo, passengers, flight crew, munitions, scientific instruments or experiments, or other equipment. Extra fuel, when optionally carried, is also considered part of the payload. In a commercial context (i.e., an airline or air freight carrier), payload may refer only to revenue-generating cargo or paying passengers.[1]

For a rocket, the payload can be a satellite, space probe, or spacecraft carrying humans, animals, or cargo. For a ballistic missile, the payload is one or more warheads and related systems; their total weight is referred to as the throw-weight.

The fraction of payload to the total liftoff weight of the air or spacecraft is known as the "payload fraction". When the weight of the payload and fuel are considered together, it is known as the "useful load fraction". In spacecraft, "mass fraction" is normally used, which is the ratio of payload to everything else, including the rocket structure.[2]

Relationship of range and payload

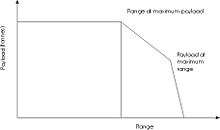

There is a natural trade-off between the payload and the range of an aircraft. A payload range diagram (also known as the "elbow chart") illustrates the trade-off.

The top horizontal line represents the maximum payload. It is limited structurally by maximum zero-fuel weight (MZFW) of the aircraft. Maximum payload is the difference between maximum zero-fuel weight and operational empty weight (OEW). Moving left-to-right along the line shows the constant maximum payload as the range increases. More fuel needs to be added for more range.

The vertical line represents the range at which the combined weight of the aircraft, maximum payload and needed fuel reaches the maximum take-off weight (MTOW) of the aircraft. If the range is increased beyond that point, payload has to be sacrificed for fuel.

The maximum take-off weight is limited by a combination of the maximum net power of the engines and the lift/drag ratio of the wings. The diagonal line after the range-at-maximum-payload point shows how reducing the payload allows increasing the fuel (and range) when taking off with the maximum take-off weight.

The second kink in the curve represents the point at which the maximum fuel capacity is reached. Flying further than that point means that the payload has to be reduced further, for an even lesser increase in range. The absolute range is thus the range at which an aircraft can fly with maximum possible fuel without carrying any payload.

Examples

Examples of payload capacity:

- Antonov An-225 Mriya: 250,000 kg

- Saturn V:

- Payload to Low Earth Orbit 118,000 kg

- Payload to Lunar orbit 47,000 kg

- Space Shuttle:

- Payload to Low Earth Orbit 24,400 kg (53,700 lb)

- Payload to geostationary transfer orbit 3,810 kg (8,390 lb)

- Trident (missile): 2800 kg throw weight

- Automated Transfer Vehicle

- Payload:[3] 7,667 kg 8 racks with 2 x 0.314 m3 and 2 x 0.414 m3

- Envelope: each 1.146 m3 in front of 4 of these 8 racks

- Cargo mass: Dry cargo: 1,500 - 5,500 kg

- Water: 0 – 840 kg

- Gas (Nitrogen, Oxygen, air, 2 gases/flight): 0 – 100 kg

- ISS Refueling propellant: 0 – 860 kg (306 kg of fuel, 554 kg of oxidizer)

- ISS re-boost and attitude control propellant: 0 - 4,700 kg

- Total cargo upload capacity: 7,667 kg

Structural capacity

For aircraft, the weight of fuel in wing tanks does not contribute as significantly to the bending moment of the wing as does weight in the fuselage. So even when the airplane has been loaded with its maximum payload that the wings can support, it can still carry a significant amount of fuel.

Payload constraints

Launch and transport system differ not only on the payload that can be carried but also in the stresses and other factors placed on the payload. The payload must not only be lifted to its target, it must also arrive safely, whether elsewhere on the surface of the Earth or a specific orbit. To ensure this the payload, such as a warhead or satellite, is designed to withstand certain amounts of various types of "punishment" on the way to its destination. Most rocket payloads are fitted within a payload fairing to protect them against dynamic pressure of high-velocity travel through the atmosphere, and to improve the overall aerodynamics of the launch vehicle. Most aircraft payloads are carried within the fuselage for similar reasons. Outsize cargo may require a fuselage with unusual proportions, such as the Super Guppy.

The various constraints placed on the launch system can be roughly categorized into those that cause physical damage to the payload and those that can damage its electronic or chemical makeup. Examples of physical damage include extreme accelerations over short time scales caused by atmospheric buffeting or oscillations, extreme accelerations over longer time scales caused by rocket thrust and gravity, and sudden changes in the magnitude or direction of the acceleration caused by how quick engines are throttled and shut down, etc. Electrical, chemical, or biological payloads can be damage by extreme temperatures (hot or cold), rapid changes in temperature or pressure, contact with fast moving air streams causing ionization, and radiation exposure from cosmic rays, the van Allen belt, or solar wind.

References

- "Payload - Define Payload at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2013-12-12.

- Launius, Roger D. Jenkins, Dennis R. 2002. To Reach the High Frontier: A History of U.S. Launch Vehicles. Univ. Pr. of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2245-8

- http://esamultimedia.esa.int/docs/ATV/FS003_12_ATV_updated_launch_2008.pdf European Space Agency

External links

- Shannon Ackert (April 2013). "Aircraft Payload-Range Analysis for Financiers" (PDF). Aircraft Monitor.

- "Using the Payload/Range and Takeoff Field Length Charts in the Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning Documents" (PDF). Boeing Commercial Airplanes. Feb 12, 2014.