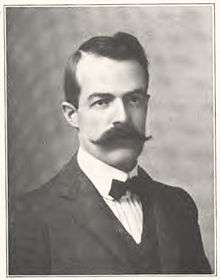

Paul P. Hastings

Paul Pardee Hastings (October 22, 1872 – September 16, 1947) was a prominent executive of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad.

Personal life

Paul Pardee Hastings was born on October 22, 1872 in the family home in Farmington, Atchison County, Kansas and died on September 16, 1947 in Saratoga, California. He was the second oldest of a family of seven. His father was Z. S. Hastings, a well-known farmer and preacher. His mother was the former Rosetta Butler, who was active in the temperance and anti-smoking movements. His mother's father was Pardee Butler, a Kansas pioneer and preacher, active in the abolition movement before the American Civil War. His youngest brother, Milo Hastings, was a well-published inventor, author, and nutritionist.

Hastings married Frances Charlotte Reed on November 20, 1901 when he was 29. They had two children: Ross Reed (b. October 19, 1903) and Marylyn (b. November 2, 1908). The first child was born in the historic Barry Goldwater house in Prescott, Arizona.

Hastings was active in local social and civic organizations. While living in Jerome, Arizona in 1900 he was president of the Blue Rock Gun club.[1] Prior to Arizona becoming a state in 1912, he was active in the anti statehood movement as one the representatives from Yavapai County in the 1905 convention.[2] He was a director of the Prescott Yavapai Club during 1905; treasurer was M. Goldwater, grandfather of Barry Goldwater.[3]

After Hastings death in 1947 one of the tugs in the fleet of Santa Fe Railroad Tugboats was named in his honor in 1948.

Professional Life: Positions Held

Hastings was educated at common schools then went to the National Business College in nearby Kansas City, Missouri.

Hastings began his railroad career on August 18, 1891 as a rate clerk with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad in Topeka 35 miles from where he was born. He retired 51 years later in 1942 at the end of the month he turned 70 as a vice-president of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad living in the San Francisco Bay area. Over the years he held the positions:

- August 1891 to March 1895, Topeka, Kansas, Revising and interline clerk in the freight auditor’s office, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.[4]

- April 1895 to September 1895, Prescott, Arizona, Freight clerk, Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway.

- October 1895 to August 1898, Prescott, Arizona, Freight clerk and traveling auditor.

- September 1898 to August 1900, Jerome, Arizona, Freight clerk, United Verde Copper Company.

- September 1900 to September 1902, Jerome, Arizona, Auditor and general freight and passenger agent, United Verde & Pacific Railway.

- October 1902 to March 1903, Independent accountant.

- April 1903 to February 1907, Prescott, Arizona, Auditor, Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway.

- March 1907 to 1912, Prescott, Arizona, General freight and passenger agent, Santa Fe Prescott and Phoenix Railway.[5]

- 1912-1918, San Francisco, California, Assistant general freight agent, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.

- 1918-1920, Washington, DC, United States Railroad Administration, Assistant director of traffic in charge of the freight rate department.

- 1921-1922, Chicago, Illinois, Member of the standing rate committee of the Transcontinental Freight Bureau.

- 1922-1936, San Francisco, California, General freight agent, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.

- 1936-1937, San Francisco, California, Assistant freight traffic manager, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.

- 1937-1942, San Francisco, California, Vice president in charge of traffic, Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad.

Professional Life: Public Testimony

Hastings frequently testified before government bodies about railroad rates. There were many issues. The various railroad lines sought rates that were to their advantage. The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) sought to see that the public was being well served. When the Panama Canal opened in 1914 there major changes were needed in the routing and rating of freight hauling. Some of his appearances were:

- October 17, 1914, Chicago, Interstate Commerce Commission. Noted that shipments by water from the Atlantic to Pacific ports doubled with the opening of the Panama Canal. In view of this competition the railroads sought to reduce transcontinental rates.[6]

- July 17, 1922, San Francisco, Shipping Board. Contended that certain features of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 would create new sea lanes between the Atlantic Coast and the Far East to the detriment of the Pacific Coast ports.[7]

- September 15, 1922, Oakland, Interstate Commerce Commission. Opposed joint rail and water rates proposed by the Southern Pacific Railroad on the grounds that they would discriminate against middle-western shippers.[8]

- September 11, 1925, Chicago, Interstate Commerce Commission. Argued that a proposed rate increase should leave the eastbound rates on perishable products to Eastern states unchanged to encourage the continued development of California agriculture.[9]

- January 15, 1929, Fresno, Interstate Commerce Commission. Along with the Southern Pacific Railroad opposed the application of the Western Pacific Railroad to build another rail line in the San Joaquin Valley as unneeded.[10]

- May 27, 1930, Washington DC, Senate Subcommittee of the Committee on Interstate Commerce. Testified on the issue of long and short haul, the desire of the railroads to set rates differently depending on the distance of travel.[11]

- June 7, 1935, Washington DC, House Sub-Committee of the Committee on Interstate Commerce. Testified on the Pettengill bill to amend the long and short haul provision of the interstate commerce act. Argued for rate leeway to enable the railroads to compete with water shipment through the Panama Canal.[12]

Notes

- The Arizona Republican, January 25, 1900

- The Arizona Republican, May 28, 1905

- The Arizona Republican, October 25, 1905

- Job history during 1891 to 1907 from Biographical directory of Officials of The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway System, Railway Exchange, Chicago, 1908

- Job history during 1907 to 1942 from the New York Times obituary of September 18, 1947, p. 25

- The Washington Post, October 18, 1914, p. E1

- Los Angeles Times, July 18, 1922, p.I22

- Oakland Tribune, September 15, 1922

- Los Angeles Times, September 12, 1925, p. 13

- Fresno Bee, January 15, 1929, Los Angeles Times, Jan 16, 1929, p. 11

- Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Interstate Commerce United States Senate on S. 563, A bill to Amend Section 4 of the Interstate Commerce Act, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, 1930

- Ogden Standard Examiner, June 7, 1935. Los Angeles Times, June 7, 1935, p. 5