Passerini reaction

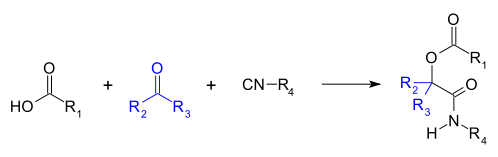

The Passerini reaction is a chemical reaction involving an isocyanide, an aldehyde (or ketone), and a carboxylic acid to form a α-acyloxy amide.[1][2][3]

| Passerini reaction | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Mario Passerini |

| Reaction type | Carbon-carbon bond forming reaction |

| Identifiers | |

| Organic Chemistry Portal | passerini-reaction |

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000244 |

This organic reaction was discovered by Mario Passerini in 1921 in Florence, Italy. It is the first isocyanide based multi-component reaction developed, and currently plays a central role in combinatorial chemistry.[4]

Recently, Denmark et al. have developed an enantioselective catalyst for asymmetric Passerini reactions.[5]

Reaction mechanism

Two reaction pathways have been hypothesized.

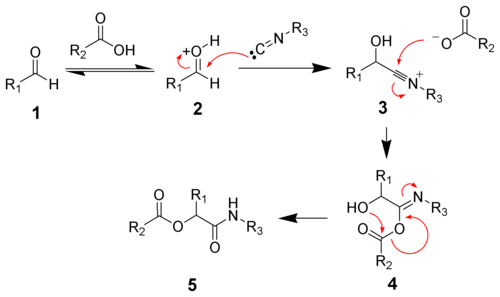

Ionic mechanism

In polar solvents such as methanol or water, the reaction proceeds by protonation of the carbonyl followed by nucleophilic addition of the isocyanide to give the nitrilium ion 3. Addition of a carboxylate gives intermediate 4. Acyl group transfer and amide tautomerization give the desired ester 5 .

Concerted mechanism

In non-polar solvents and at high concentration a concerted mechanism is likely:[6]

This mechanism involves a trimolecular reaction between the isocyanide (R–NC), the carboxylic acid, and the carbonyl in a sequence of nucleophilic additions. The transition state TS# is depicted as a 5-membered ring with partial covalent or double bonding. The second step of the Passerini reaction is an acyl transfer to the neighboring hydroxyl group. There is support for this reaction mechanism: the reaction proceeds in relatively non-polar solvents (in line with transition state) and the reaction kinetics depend on all three reactants. This reaction is a good example of a convergent synthesis.

Scope

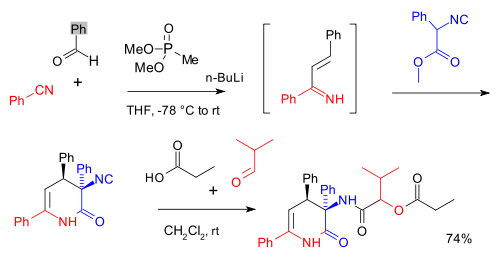

The Passerini reaction is used in many multicomponent reactions. For instance one preceded by a Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons reaction and forming a depsipeptide:[7]

Passerini multicomponent reactions have found use in the preparation of polymers from renewable materials.[8]

See also

References

- Passerini, M.; Simone, L. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1921, 51, 126–29.

- Passerini, M.; Ragni, G. Gazz. Chim. Ital. 1931, 61, 964–69.

- Banfi, L.; Riva, R. (2005). The Passerini Reaction. Org. React. 65. pp. 1–140. doi:10.1002/0471264180.or065.01. ISBN 978-0471264187..

- Dömling, A.; Ugi, I. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2000, 39, 3168–3210. (Review)

- Denmark, S. E.; Fan, Y. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 9667–76. doi:10.1021/jo050549m

- The Passirini Reaction L. Banfi, R.Riva in Organic Reactions vol. 65 L.E. Overman Ed. Wiley 2005 ISBN 0-471-68260-8

- A Flexible Six-Component Reaction To Access Constrained Depsipeptides Based on a Dihydropyridinone Core Monica Paravidino, Rachel Scheffelaar, Rob F. Schmitz, Frans J. J. de Kanter, Marinus B. Groen, Eelco Ruijter, and Romano V. A. Orru J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 10239–42 doi:10.1021/jo701978v

- Kreye, O.; Tóth, T.; Meier, M. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2011, 133 (6), pp 1790–1792 doi:10.1021/ja1113003