Particle deposition

Particle deposition is the spontaneous attachment of particles to surfaces. The particles in question are normally colloidal particles, while the surfaces involved may be planar, curved, or may represent particles much larger in size than the depositing ones (e.g., sand grains). Deposition processes may be triggered by appropriate hydrodynamic flow conditions and favorable particle-surface interactions. Depositing particles may just form a monolayer which further inhibits additional particle deposition, and thereby one refers to surface blocking. Initially attached particles may also serve as seeds for further particle deposition, which leads to the formation of thicker particle deposits, and this process is termed as surface ripening or fouling. While deposition processes are normally irreversible, initially deposited particles may also detach. The latter process is known as particle release and is often triggered by the addition of appropriate chemicals or a modification in flow conditions.

Microorganisms may deposit to surfaces in a similar fashion as colloidal particles. When macromolecules, such as proteins, polymers or polyelectrolytes attach to surfaces, one rather calls this process adsorption. While adsorption of macromolecules largely resembles particle deposition, macromolecules may substantially deform during adsorption. The present article mainly deals with particle deposition from liquids, but similar process occurs when aerosols or dust deposit from the gas phase.

Initial stages

A particle may diffuse to a surface in quiescent conditions, but this process is inefficient as a thick depletion layer develops, which leads to a progressive slowing down of the deposition. When particle deposition is efficient, it proceeds almost exclusively in a system under flow. In such conditions, the hydrodynamic flow will transport the particles close to the surface. Once a particle is situated close to the surface, it will attach spontaneously, when the particle-surface interactions are attractive. In this situation, one refers to favorable deposition conditions. When the interaction is repulsive at larger distances, but attractive at shorter distances, deposition will still occur but it will be slowed down. One refers to unfavorable deposition conditions here. The initial stages of the deposition process can be described with the rate equation[1]

where Γ is the number density of deposited particles, t is the time, c the particle number concentration, and k the deposition rate coefficient. The rate coefficient depends on the flow velocity, flow geometry, and the interaction potential of the depositing particle with the substrate. In many situations, this potential can be approximated by a superposition of attractive van der Waals forces and repulsive electrical double layer forces and can be described by DLVO theory. When the charge of the particles is of the same sign as the substrate, deposition will be favorable at high salt levels, while it will be unfavorable at lower salt levels. When the charge of the particles is of the opposite sign as the substrate, deposition is favorable for all salt levels, and one observes a small enhancement of the deposition rate with decreasing salt level due to attractive electrostatic double layer forces. Initial stages of the deposition process are relatively similar to the early stages of particle heteroaggregation, whereby one of the particles is much larger than the other.

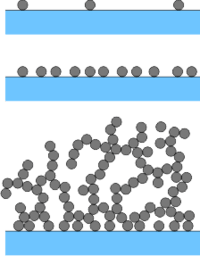

Blocking

When depositing particles repel each other, the deposition will stop by the time when enough particles have deposited. At one point, such a surface layer will repel any particles that may still make attempts to deposit. The surface is said to be saturated or blocked by the deposited particles. The blocking process can be described by the following equation[2]

where B(Γ) is the surface blocking function. When there are no deposited particles, Γ = 0 and B(0) = 1. With increasing number density of deposited particles, the blocking function decreases. The surface saturates at Γ=Γ0 and B(Γ0) = 0. The simplest blocking function is[3]

and it is referred to as the Langmuir blocking function, as it is related to the Langmuir isotherm.

The blocking process has been studied in detail in terms of the random sequential adsorption (RSA) model.[4] The simplest RSA model related to deposition of spherical particles considers irreversible adsorption of circular disks. One disk after another is placed randomly at a surface. Once a disk is placed, it sticks at the same spot, and cannot be removed. When an attempt to deposit a disk would result in an overlap with an already deposited disk, this attempt is rejected. Within this model, the surface is initially filled rapidly, but the more one approaches saturation the slower the surface is being filled. Within the RSA model, saturation is referred to as jamming. For circular disks, jamming occurs at a coverage of 0.547. When the depositing particles are polydisperse, much higher surface coverage can be reached, since the small particles will be able to deposit into the holes in between the larger deposited particles. On the other hand, rod like particles may lead to much smaller coverage, since a few misaligned rods may block a large portion of the surface.

Since the repulsion between particles in aqueous suspensions originates from electric double layer forces, the presence of salt has an important effect on surface blocking. For small particles and low salt, the diffuse layer will extend far beyond the particle, and thus create an exclusion zone around it. Therefore, the surface will be blocked at a much lower coverage than what would be expected based on the RSA model.[5] At higher salt and for larger particles, this effect is less important, and the deposition can be well described by the RSA model.

Ripening

When the depositing particles attract each other, they will deposit and aggregate at the same time. This situation will result in a porous layer made of particle aggregates at the surface, and is referred to as ripening. The porosity of this layer will depend whether the particle aggregation process is fast or slow. Slow aggregation will lead to a more compact layer, while fast aggregation to a more porous one. The structure of the layer will resemble the structure of the aggregates formed in the later stages of the aggregation process.

Experimental techniques

Particle deposition can be followed by various experimental techniques. Direct observation of deposited particles is possible with an optical microscope, scanning electron microscope, or the atomic force microscope. Optical microscopy has the advantage that the deposition of particles can be followed in real time by video techniques and the sequence of images can be analyzed quantitatively.[6] On the other hand, the resolution of optical microscopy requires that the particle size investigated exceeds at least 100 nm.

An alternative is to use surface sensitive techniques to follow particle deposition, such as reflectivity, ellipsometry, surface plasmon resonance, or quartz crystal microbalance.[5] These techniques can provide information on the amount of particles deposited as a function of time with good accuracy, but they do not permit to obtain information concerning the lateral arrangement of the particles.

Another approach to study particle deposition is to investigate their transport in a chromatographic column. The column is packed with large particles or with a porous medium to be investigated. Subsequently, the column is flushed with the solvent to be investigated, and the suspension of the small particles is injected at the column inlet. The particles are detected at the outlet with a standard chromatographic detector. When particles deposit in the porous medium, they will not arrive at the outlet, and from the observed difference the deposition rate coefficient can be inferred.

Relevance

Particle deposition occurs in numerous natural and industrial systems. Few examples are given below.

- Coatings and surface functionalization. Paints and adhesives often are concentrated suspensions of colloidal particles, and in order to adhere well to the surface the particles must deposit to the surface in question. Deposits of a monolayer of colloidal particles can be used to pattern the surface on a μm or nm scale, a process referred to as colloidal lithography.[7]

- Filters and filtration membranes. When particle deposit to filters or filtration membranes, they lead to pore clogging a membrane fouling.[8] When designing well functioning membranes, particle deposition must be avoided, and proper functionalization of the membranes is essential.

- Deposition of microorganisms. Microorganisms may deposit similarly to colloidal particles. This deposition is a desired phenomenon in subsurface waters, as the aquifer filters out eventually injected microorganisms during the recharge of aquifers.[9] On the other hand, such deposition is highly undesired at the surface of human teeth as it represent the origin of dental plaques. Deposition of microorganisms is also relevant in the formation of biofilms.

See also

References

- W. B. Russel, D. A. Saville, W. R. Schowalter,Colloidal Dispersions,Cambridge University Press, 1989.

- M. Elimelech, J. Gregory, X. Jia, R. Williams, Particle Deposition and Aggregation: Measurement, Modelling and Simulation, Butterworth-Heinemann, 1998.

- Z. Adamczyk, Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 100, 267-347.

- J. W. Evans, Rev. Mod. Phys. 65 (1993) 1281-1329.

- M. R. Bohmer, E. A. van der Zeeuw, G. J. M. Koper, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 197 (1998) 242-250.

- Y. Luthi, J. Ricka, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 206 (1998) 302-313.

- R. Michel, I. Reviakine, D. S. Sutherland, G. Fokas, G. Csucs, G. Danuser, N. D. Spencer, M. Textor, Langmuir 18 (2002) 8580-8586.

- X. Zhu, M. Elimelech, Environ. Sci. Technol. 31 (1997) 3654-3662.

- S. F. Simoni, H. Harms, T. N. P. Bosma, A. J. B. Zehnder, Environ. Sci. Technol. 32 (1998) 2100-2105