Parsons Horological Institute

Parsons Horological Institute (originally, La Porte School for Watchmakers; also known as Parsons Horological School) was the first horological school in the United States. It was founded in 1886, in La Porte, Indiana. In 1898, it moved to Peoria, Illinois, eventually becoming a department of what is now Bradley University.

Environment

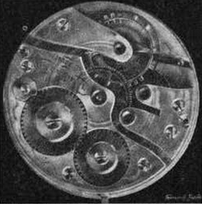

While timepieces of foreign make were mainly sold and used in the US in the 19th century, the watch repairer needed fitness for his work, which could be acquired only by long apprenticeship and familiarity with the various types of timepieces. When American watches became popular, watchmaking as a trade began to decline. Materials of every description became plentiful, easily obtained and readily used, and any difficult job was naturally turned over to the manufacturer. Still, these conditions, as regards American watches, afforded no reason why watchmakers should degenerate. On the contrary, every improvement and modification of timepieces and every additional form of movement called for higher skill in handling these delicate machines.[1]

The idea of a school for watchmakers was first conceived by James R. Parsons (born in Michigan, circa 1847), of La Porte, Indiana. He was himself experienced in watchwork and felt that what he had spent so many of the best years of his life in learning, could be taught in much less time in a horological school. Besides, in his trade, he had found it hard to get the work done in a workmanlike manner and he saw the large and increasing field of labor for skilled workmen. Just at this time a letter from a young man appeared in one of the journals, asking if there was no school where a young man could learn the watch trade. The letter stated that the writer had started to learn the trade but was forced to give it up on account of the death of his employer. The young man had gone to a great number of the watch factories but no one would teach him.[2]

Founding in Indiana

The idea being born, Parsons at once determined to establish a horological school and as a result, in 1886, the first school for watchmakers in America was opened in La Porte. The school steadily grew and in 1888, new rooms were provided, affording ample accommodations for 100 students and making possible the pursuit of a greater number of lines of work.[2] The development of the institute was so rapid as to render it difficult for the founder to keep pace with the requirements. After the success of the school had been assured, several offers of considerable sums of money were made to remove the school to other places.[1]

After six very successful years, the school again felt the need of increased accommodations and facilities to keep pace with the growing demand. Hence it was thought advisable not only to provide for a larger number of students, but also to increase the number of branches taught and to produce a higher grade of work.[2]

Relocation to Illinois

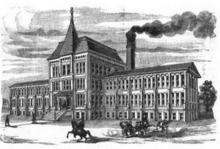

In 1892, Lydia Bradley, of Peoria, Illinois, became interested in the school, and being desirous of assisting deserving young men and women who wished to learn the trade, offered to provide a larger building together with all necessary equipment. Arrangements were accordingly made and in 1892 the school moved to its new quarters, in a large building in Peoria, Illinois, formerly occupied by the Peoria Watch Factory. The school was still called "Parson's Horological School," but was under the management of Parsons, Ide & Co.[2] Parsons, Ide & Company of Peoria, Illinois, incorporated to conduct Parsons' Horological Institute as a school of theoretical instruction in watchmaking, jewelry manufacturing and optics, and to manufacture jewelry, special instruments, and so forth. The capital stock was US$120,000 and the incorporators were James R. Parsons, Fred F. Ide and Lydia Bradley.[3]

In 1896, the school was burned out, but this was not permitted to interfere with its work. It was at once moved into a building, which had been erected for a. dormitory, where it remained only a short time. In 1897, it was incorporated with Bradley Polytechnic Institute, and since that time has been known as the Horological Department of Bradley Polytechnic Institute. The building is the only one in the United States that has been erected solely for use as a Horological school.[2]

When the Bradley Polytechnic Institute was opened in 1897, in Peoria, and affiliated with the University of Chicago, the most significant action of the trustees was the incorporation into the plan of the institution of the Parsons Horological School, which had existed for eleven years and ranked as the leading watchmaking school of the country. The significance of the action lay in the intention to teach specific trades in addition to technical skill. The Horological School, fully equipped as it was, and with a 100 students enrolled, was taken as it existed and made a model of the numerous special trade schools that were later added to Bradley.[4]

Special exercises marked the formal opening of the Horological Building, November 19th, 1897, in Peoria, Illinois. A detailed history of the school was given by Parsons. Theodore Gribi of Chicago, gave the leading address on the topic "Watchmaking, Past and Present." It was a history of the development of watchmaking and the allied trades in Germany, England, France and the United States. This was followed by an address entitled "Then and Now" by Mr. J. H. Purdy of Chicago, which contrasted the conditions of a generation ago with those of the present day. President William R. Harper of the University of Chicago and a trustee of the Institute, closed the program with brief remarks.[2]

Coursework

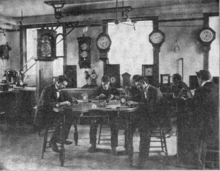

While based in Indiana, students were taught the art of making high grade chronometers and fine lever watches from raw material. Engraving and optician's work, were also taught, and pupils were required to master every detail of the work.[5]

After the move to Illinois, the object of the institute was not to make money, but to turn out competent watchmakers and jewelers. The institute gave the student a thorough education in horology, including instructions in making watches, chronometers, clocks and horological machinery in general, as well as repairing the same. It gave a course in optics, and in this department graduates received a separate diploma.[1]

Similar American schools of watchmaking included the Chicago Watchmakers' Institute, Chicago, Illinois; Elgin Horological Institute, Elgin, Illinois; Saint Louis Watchmakers' School, Saint Louis, Missouri; and Woodcock's School for Watchmakers, Winona, Minnesota.[5]

Equipment

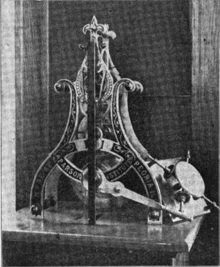

The equipment has kept pace with the growth of the school and as of 1908, no institution of its kind offered better facilities for instruction. There were several large lathes for general use, also a dynamo for plating, a shaper, a large power fiat roll, one hand roll with square, flat and ring rolls, a transit instrument, a chronometer, and many other necessary articles of equipment. Besides, each student had a lathe at his own bench with all necessary attachments. Materials are kept in stock so that no one need waste valuable time waiting for orders to be filled.[2]

Enrollment

Women were admitted to the institute on the same terms as men.[1] In 1891, 29 pupils were enrolled.[5] The following year, it was reported that the average attendance generally was in excess of 100.[6] The attendance was very large by 1898, nearly equal to that of all the other schools of the kind combined.[1] In 1908, it was reported that of the more than 3,000 students who received instruction in this school, about 15 came from foreign countries, the rest from the United States. The enrollment for the year 1906-7 was a little more than 200.[2]

References

- Scientific American, Incorporated 1898, p. 23.

- Bradley Polytechnic Institute 1908, p. 107-09.

- Jewelers' Circular Publishing Company 1893, p. 28.

- Modern Machinery Publishing Company 1898, p. 275-77.

- Commissioner of Labor 1893, p. 100.

- Touche & Potter 1892, p. 215.

Attribution

Bibliography

- Bradley Polytechnic Institute (1908). Bradley Polytechnic Institute: The First Decade, 1897-1907 (Public domain ed.). Bradley Polytechnic Institute.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Commissioner of Labor (1893). Annual Report of the Commissioner of Labor (Public domain ed.). U.S. Government Printing Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jewelers' Circular Publishing Company (1893). The Jewelers' Circular and Horological Review. 27 (Public domain ed.). Jewelers' Circular Publishing Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Modern Machinery Publishing Company (1898). Modern machinery : a monthly journal of mechanical progress. 3–4 (Public domain ed.). Chicago: Modern Machinery Publishing Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scientific American, Incorporated (1898). Scientific American (Public domain ed.). Scientific American, Incorporated.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Touche, Royal L. La; Potter, John Henry (1892). Chicago and Its Resources Twenty Years After, 1871-1891: A Commercial History Showing the Progress and Growth of Two Decades from the Great Fire to the Present Time. Chicago Times Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links